Against police history.

For those who despise nostalgia, the fiftieth anniversary of 1968 must have been a relief. The rebellions of the era were not smugly celebrated in the United States, far from it. Many of the most outspoken and committed radicals of the era like Abbie Hoffman and Daniel Berrigan are no longer alive to give fresh media commentary, so retrospectives were often dominated by devotees of nonviolence who believed that most of the lessons to be derived from the late sixties were negative. 1968 and its aftermath were scrutinized through the lens of present-day political struggle and their example found wanting. The curiously stillborn and furiously co-opted #resistance against Donald Trump would only lose further ground if it were to manifest an openly insurrectionary and anti-capitalist character, it was said. Pacifist organizer Robert Levering wrote that most of the actions at the ’68 Democratic National Convention were completely counterproductive, going so far as to imply that militant protesters—including Students for a Democratic Society cofounder Tom Hayden—were responsible for prolonging the war they were trying to stop. Ex-Weathermen spokesman Mark Rudd lamented that “what Antifa does and what we did in the Weather Underground are exactly what the cops want.” For the coup de grace, ex-SDS official and full-time apostate Todd Gitlin proclaimed that 1968 was actually the “year of counter-revolution.”

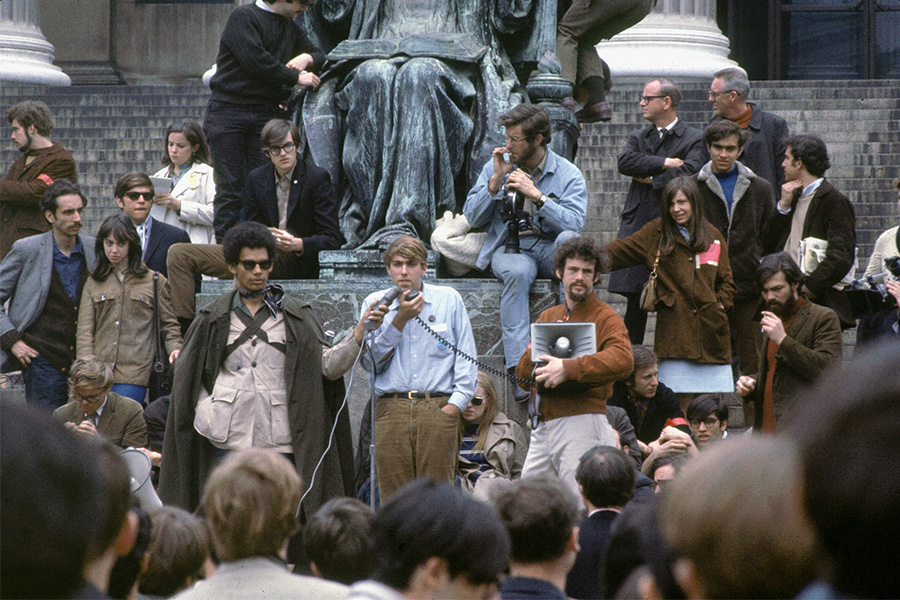

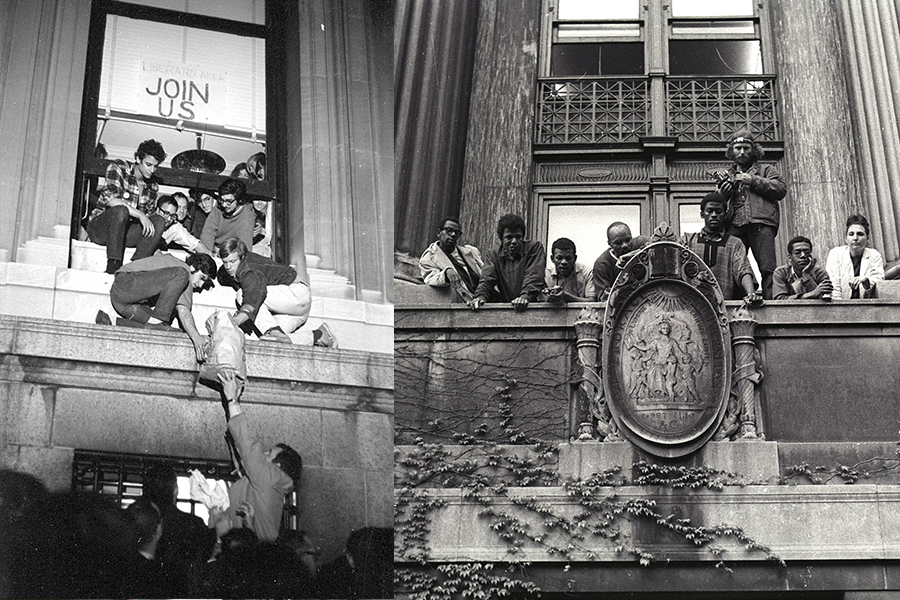

The most seemingly credible retrospective came from Rudd. Rudd was once an icon of youth rebellion, helping to lead the famed 1968 Columbia University occupation. The most visible of his musings was a New York Times op-ed where he pointed out that “what made the [Columbia] protests so powerful” was “the leadership of black students.” But his most thorough statement of purpose was a feature interview with Chris Hedges where he excoriated the militancy of the late sixties, made similar condemnations of contemporary anti-fascists, and espoused “practical pacifism.”

In Hedges’s article, Rudd holds up Columbia ’68 as a strictly nonviolent protest and therefore “an example of the kind of strategy that the left has to adopt.” Rudd counterposes his insurrectionary Weathermen days with the “mass movement” that had arisen at Columbia. Forceful protest doesn’t even qualify as strategy to Rudd, but is “pure self-expression”—catharsis which only causes backlash and disunity, and must be avoided at all costs.

It’s easy enough to denounce the excesses of the Weathermen: their Leninist vanguardism, their fetishization of the North Vietnamese state, their early flirtation with terrorist bloodshed—the humanist heart intuitively shrinks from such tendencies. But to try and sever ultra-militancy as a whole from the accomplishments of the late sixties is flamboyantly deceptive. Exhibit A is Rudd’s own New York Times piece on Columbia ’68, where he mentions that “in a loose alliance with the Student Afro-American Society (SAAS)…we even held the dean of the college hostage in his office.” Another example is this recollection of the beginning of the protests recently given by SAAS leader Raymond Brown to Vanity Fair: “The students were trying to rip down the [twelve-foot-high] chain-link fence around the gym site, and some of the cops got in a wrestling match with the students, including a couple of good friends of mine.”

“The Columbia administration was terrified of what Harlem might do if the police were called,” Rudd wrote cryptically in the Times. “Administrators waited a week as the occupations and support demonstrations grew, and Columbia became worldwide news.” Again Raymond Brown is more forthcoming: in a strategy session with H. Rap Brown and other Black Power leaders, the SAAS agreed that “you’re in this position where you’re counting on the fear of the police and the city administration that Harlem will react violently if you’re mistreated.”

That same April, Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated, leading to “the Holy Week Uprising.” As historian Peter Levy notes, “looting, arson or sniper fire occurred in 196 cities…Not until over fifty-eight thousand National Guardsmen and regular Army troops joined local state and police forces did the uprising cease.” Columbia administrators could still see fires smoking from their office windows. “You cannot understand the Columbia student revolt without understanding that it happened three weeks after Martin Luther King, Jr. was killed,” Juan Gonzalez once pointed out. “At that point, it wasn’t a question of what career you were going to choose, it was a question of whether the country would survive a civil war.” Thus, while Rudd scolds us all for erasing black resistance at Columbia, he himself whitewashes the national black revolt—cited by historians as “the largest domestic disorder since the Civil War”—which made it possible.

“Activists will never design good strategy on the basis of bad history.”

Even more outrageously, Rudd attempts to smear the Black Power movement as a whole. “Black power was no more embraced by the black masses than the violence and rhetoric of the Weather Underground were embraced by the white masses,” he declaims to Hedges. “The black power movement . . . was not strategic. We fell for this bullshit.” This is white arrogance of a very high degree.

If bullshit is the issue, we—again—need look no further than Rudd’s own writing to see that he’s the one laying the cow pie. The Columbia occupation began on the premise of preserving Harlem park land from development by the university to build the college gymnasium. “Local political leaders, black activists, revolutionaries, and elders bearing hot food all trekked in to support,” Rudd recalled in the Times. But what sort of action were these masses coming to endorse? One which was represented in person by insurrectionists Stokely Carmichael and H. Rap Brown, who in turn were invited by the SAAS. When Rap Brown spoke to the occupation, he said of the proposed gymnasium: “If they build the first story, blow it up. If they sneak back at night and build three stories, burn it down. And if they get nine stories built, it’s yours. Take it over, and maybe we’ll let them in on the weekends.”

In his book The Great Uprising, Peter Levy points out that “most blacks who participated in the [ghetto] revolts were working class.” They “were not the riffraff . . . they were more likely to be over thirty than juveniles and employed as blue-collar workers than unemployed.” Among the testimonials Levy gathered is that of a Baltimore priest who caught one of his parishioners rioting. “Nobody’s listening,” the man told his pastor, “maybe blood flowing in the streets is what it takes.”

When judging Mark Rudd’s denunciations of the New Left, it’s important to consider his relation to it. As the ex-militant himself admitted, he received his first demotion within the Weathermen in January 1970. This wasn’t because he was a critic of terroristic excess; to the contrary, it appears to be because he was a particularly irrational zealot. This is affirmed by the justification for his second demotion: his direct connection to the notorious “Townhouse bombing” which accidentally killed three Weathermen comrades. In addition, according to SDS historian Kirkpatrick Sale, Rudd’s “arrogant manner, his sexist attitudes, and his political ignorance alienated his colleagues,” leaving Rudd “an unhappy loner . . . an obvious man out” by 1972.

Perhaps this bitterness is why Rudd can step beyond mere bullshitting to outright deception at times. One such example is his claim that the Weather Underground permanently “split the anti-war movement over the bogus issue of armed struggle,” and that this was “the worst thing of all, of all the things we did.” But in reality there were ongoing alliances between the pacifist and militant wings of the antiwar struggle—this was one of its strengths in the Nixon years. In 1970, several members of the Catholic left, including Father Daniel Berrigan and Mary Moylan, fled from their prison sentences for disrupting draft board offices and became fellow travelers in the underground. During this period, Berrigan and the Weathermen addressed each other warmly in public communiques. Moreover, the militants regularly assisted the Catholic leftists, to the point where Mary Moylan became a full-fledged Weather Underground member by the late 1970s.

While liberals sometimes acknowledge that Berrigan wrote the Weathermen to counsel nonviolence, they seldom note that he credited them with “one of the few momentous choices in American history” for risking the loss of their class privileges to fight for the dispossessed. Elsewhere in this letter, the nonviolent priest celebrated the Black Panthers for their commitment to self-defense. Pacifist historian Matt Meyer writes that Daniel Berrigan saw himself and the Weathermen as comrades, “indelibly connected as saboteurs together in struggle.”

There is yet another layer of shameful irony here: In August 1966, well before any of the Berrigan actions, the Stokely Carmichael-led SNCC disrupted an Atlanta draft board, with one organizer being charged by the state with “insurrection.” Thus the Catholic left tactics which Hedges and Rudd valorize were actually pioneered by the very Black Power militants they denigrate.

_____

If Mark Rudd is an increasingly popular figure in corporate and pacifist media circles, it’s because he affirms the narrative of the sixties that these parties would like us to believe: In the beginning, a nonviolent civil rights movement won great advancements for African Americans and inspired a War on Poverty. By mid-decade, it was on its way to speedily ending the Vietnam War—then those spoiled baby boomers started indulging LSD/Red Guard/oedipal fantasies of killing their parents, and derailed the movement into counterproductive violence. This is what historian John D’Emilio calls “the myth of two sixties—one good, one bad.”

Activists will never design good strategy on the basis of bad history. The reality is that the Good Sixties civil rights movement was most successful when it operated with a de facto diversity of tactics. Francis Fox Piven has noted that civil rights progress only really occurred when self-defense against white incursions escalated into black aggression against the symbols and agents of white domination—notably the white police, merchants, and landlords:

In 1961 and 1962, “freedom riders” and other activists were the targets of violence by whites in one place after another…By 1963 however, white aggression began to precipitate a black response, usually taking the form of mass rioting, as in Birmingham, Savannah, and Charleston.

Most of Rudd’s denunciations of the Bad Sixties have been heard before from moderate SDSer Todd Gitlin. A major reason why Gitlin considers 1968 to have been a setback for the left is that it was the year in which nonviolence ceased to be predominant in SDS. Yet there is substantial reason to believe that ’68 was also the year that SDS became a truly revolutionary organization. By Gitlin’s own acknowledgement, in the first half of the sixties SDS was essentially a liberal think tank that “was not known for doing anything on its own, either as a national group or (with few exceptions) in its chapters . . . this bullshit talk organization that put out a lot of smart working papers and talked a lot, but didn’t do anything.” Finally, in mid-1964, the students launched the Economic Research and Action Programs (ERAP), and began anti-poverty organizing in American ghettos. But SDS quickly came to realize that where empowerment of the poor did emerge, it had little to do with nonviolence or professional organizing. ERAP’s Tom Hayden experienced the Newark rebellion of 1967 up close and wrote an admiring cover story—illustrated with a sketch of a Molotov cocktail—for the New York Review of Books. In his memoir, Gitlin recalled Hayden’s keynote address to an SDS conference in Michigan that year, where he proposed that “rifle practice was the next step; we might need to know how to break off friendships and become urban guerrillas.” Even still, it wasn’t until 1968, with the rise of the Weathermen, that J. Edgar Hoover took the trouble to bug SDS’s national office.

“The massacre at My Lai, the rejection of peace terms, the assassination of Fred Hampton, the invasion of Cambodia, all ‘made a moral mockery of appeals for gradual change.'”

Gitlin has repeatedly argued that protest violence leads to long-term isolation and counterrevolution and that the collapse of SDS is a prime example of this. The problem with this theory is that the antiwar movement actually thrived in the aftermath of the organization’s demise in 1969. In the early 1970s, “the growth and radicalization of the movement continued at a rapid pace not seen since the populist and radical labor movements,” wrote Tom Hayden in his 2017 book-length analysis of the movement, Hell No. “The greatest student strike in US history shut down campuses for weeks” in May 1970, in spite of the fact that President Nixon had withdrawn two hundred thousand troops from Vietnam in the previous year. “536 schools were shut down completely for some period of time, 51 of them for the entire year.” Revolutionaries perpetrated over a hundred arsons of government offices and dozens of bombings during the strike. By the end of it, the ACLU endorsed immediate troop withdrawal for the first time, and House Democrats introduced their original resolution to impeach Nixon. In June, Nixon told J. Edgar Hoover that “revolutionary terror” represented the single greatest threat to American society, and hurriedly aborted his invasion of Cambodia. Historians now agree that the president’s fear of student unrest and black militancy led him directly down the road of recklessly counterproductive repression and his downfall with Watergate.

“Organizing is important in the long buildup of prior movements and past experiences of victory and defeat,” writes Hayden in Hell No. “But there always seems to be an unpredicted moment when a new chapter of social movement history begins.” When it comes to the movements of the late sixties and early seventies, Hayden (echoing George Katsiaficas’s The Imagination of the New Left) posits that this moment came in the aftermath of 1968: specifically, the years 1970, when nearly a thousand American GIs attempted to kill their officers (over two hundred succeeded); and 1971, when the largest antiwar protest up to that point in history occurred in Washington. By then, reports Rick Perlstein, one could find “construction workers and farmers among the obscenity-shouting ranks of the antiwar forces.” These were also the years in which the draft was phased out and a constitutional amendment was passed to lower the voting age in order to foster less violent forms of dissent among students. The movement’s overwhelming, unifying passion compensated for its informal coordination and divergent tactics, rendering a permanent organization like SDS redundant. Even Gitlin admits as much: “The antiwar movement was far more than the alphabet soup of organizations that tried to lead or at least influence it,” he wrote in the book version of Ken Burns’s documentary The Vietnam War. “It did not have a headquarters or officers.” The movement was simply too “contentious, irregular, raucous, and immense” to have a single policy—particularly on violence and nonviolence.

Tom Hayden didn’t survive to see the fiftieth anniversary of 1968, but some of his most trenchant assessments of the period came several years ago in a review of Mark Rudd’s memoirs. Hayden firmly rejected Rudd’s efforts to “reduce this collective rebellion to Freudian categories reserved for individual diagnoses.” To the contrary, he wrote, “There is a logical sequence from protest to resistance in the late 1960s . . . Resistance escalated as the authorities chose to escalate.”

The massacre at My Lai, the rejection of peace terms, the assassination of Fred Hampton, the invasion of Cambodia, all “made a moral mockery of appeals for gradual change.” The turn to revolutionary violence “took place as necessary reforms were rejected by the authorities,” and “in less than a decade, there were more than 100 violent rebellions in American cities.” This massive, Black Power–inspired phenomenon was a social movement unto itself; Peter Levy now calls it “the Great Uprising.”

It’s typical of white liberals to celebrate social change without recognizing how the sausage got made, but Rudd is now joining Gitlin in making a career of active obfuscation. Rudd decries the sophisticated rationalizations that he had previously used in the Weathermen to justify terroristic proposals, observing that sixties militants could “talk ourselves into anything.” Today, he’s wiser and more objective, telling Chris Hedges, “I have a bumper sticker on the back of my car that says don’t believe everything that you think.” But Rudd is as much of a narrow zealot as he ever was—it’s just that now nonviolence is his unquestionable dogma.

“Elements of the 1968 Columbia rebellion are inspiring and instructional for today’s students, protesters, and community residents,” concludes historian Stefan M. Bradley in his case study Harlem vs. Columbia University. The statement holds for New Left militancy as a whole. It bears consideration, of course, that the sixties insurrectionists lived in truly apocalyptic times: the Vietnam War killed hundreds or more every single week, and the threat of nuclear war was very real. Yet it is today’s millennials and their children who face the crises of climate change, mass extinction, and an accompanying rise of fascism. With these existential threats before the current generation, the real lessons of 1968 still have a great deal to teach us.