Everything is on the table.

I wake up and turn on the radio to hear the Today Programme on BBC Radio 4. Iran has released 85,000 prisoners, I hear. Next, a businessman is desperate. He is rejecting the unprecedented loan package announced by the UK government yesterday. Asked what he wants the government to do for his staff, he replies, “Pay their wages, just pay their wages.” The tube flickers past at the end of my garden, ghost carriage after ghost carriage carrying only a few people dispersed at intervals in the rush-hour new normal. On the radio, they discuss food rationing in the face of panic buying. The supermarket chain Sainsbury’s have announced a time slot dedicated to the over-seventies so they can avoid infection. Life is changing fast, politics too. Mortgage holidays, renters protected, prisons emptying, reduction of commercial business rates: the structures that hem us in to the fabric of everyday capitalist life are fraying fast.

COVID-19 is running amok across the globe, racing along transit routes and through neighborhoods. Everything is closing down, the life-blood of our cultural lives trickling away, businesses shutting up shop, and our physical worlds shrinking fast. Thankfully, many of us have our digital lives, still. For now, at least. I have concerns about the sustainability of the world wide web in the face of widespread infection and death but I also don’t know enough about how the web is maintained. If everyone at Virgin Media is sick or dead, will I still have broadband? I do not know, although I am sure the direct debit will continue to take money from my account every month, even if I have expired in a hospital corridor.

What is happening is a strange feeling for many, but for me it feels extremely familiar, which is, in itself, uncanny. I spent four years researching a PhD on plague—as a disease and as a metaphor for all sorts of things, including other infectious diseases, real and fictional. I spent a further two years turning that thesis into a book. I had years of contagion dreams, some of which made it into my pamphlet of poems, Apocalypse Dreams. I know an awful lot about contagious times and how people behave in them. It’s true that I never thought I’d live through it, but now I am beginning to, I find I know these feelings and I am expecting them, have them somewhere in my researcher muscle memories.

London, where I live, is an infection hot spot. I stay indoors, mostly. My mother, in her seventies with diabetes, tells me she feels like a leper. I tell her she is living through a historic moment which will result in social change on a scale unseen in her lifetime. I tell her to stay inside. My sister-in-law calls, worried. The UK has not yet closed schools but she is asthmatic and has kept her daughters home. A child at their school is infected. I reassure her: soon, very soon, the schools will close. Minutes after our call, Boris Johnson, the UK’s shambolic, blustering Prime Minister, suggests that school closures are imminent. In fact, schools are already making their own decisions in the face of staff and pupil sickness; so are parents. In the UK at moment, citizens, businesses, and institutions are proving to be one step ahead of the government.

What can I tell you about contagious epidemics? What will happen to us? Soon, we will see people scared of one another. Soon, a celebrity with COVID-19 will die. Soon, infected houses will display a sign warning delivery drivers and neighbours. Or non-infected houses will, attempting to reassure. Soon, there will be pets without owners, newly made strays fending for themselves. The most vulnerable will suffer even more. Domestic violence rates will sky-rocket. We will see armed forces patrol the streets. We will tell each other incredible stories we have heard of cruelty, of misery, but also of heroism, of generosity. There will be social unrest. There will be cult weirdos and strange beliefs, doomsters baying about the end of times. There will be exploiters, quacks, and fraudsters. But there will also be simple kindnesses, more phone calls between family members, between friends. We will all work less, if at all. There will be absurdity. And there will be incredible community support, for the people by the people. There will be ingenious new forms of entertainment and the revival of older forms that we have forgotten or stashed at the back of the cupboard. There will be incredible boredom and a lot of cleaning. This is what my knowledge tells me.

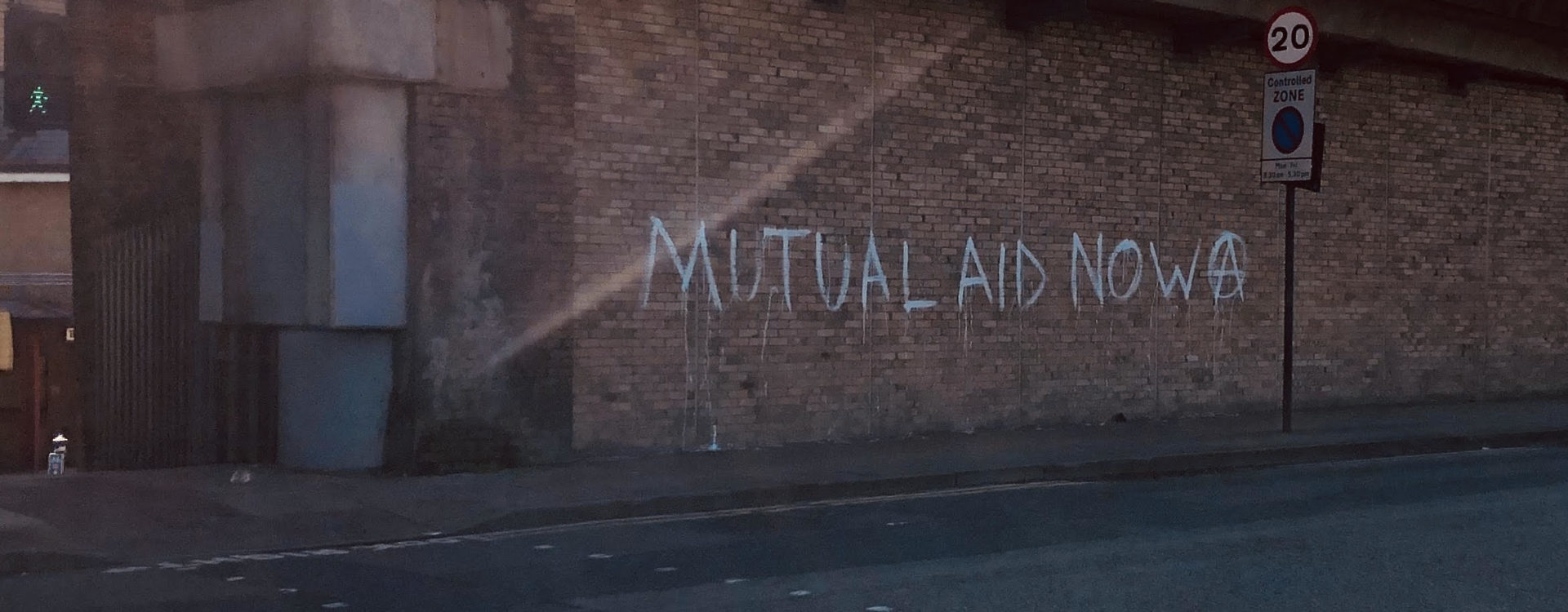

In times of social distancing, self-isolation, and lockdown the world gets smaller and we return to a state where immediate community matters more. Whether your neighbour survives may depend upon you, whether the man who lives two doors down from us gets to hospital may depend upon our car. We have already given him our number. Facebook groups have started for postcodes or streets or villages. Lists are circulating for you to sign up to help those in your area by shopping for them, collecting medicines, or simply to chat on the phone to assuage some of the loneliness for those unable to go out. People are doing this themselves. People, it turns out, know how to organise themselves. Activists among us already know this. In some cases, they are leading these projects, but new activists are being born as I type.

In 1722, fearing bubonic plague’s return to England after its appearance at a French port, Daniel Defoe wrote Journal of the Plague Year, based on the 1665 outbreak during which he had been an infant. He also wrote a shorter, lesser known and less entertaining tract, Due Preparations for the Plague or, to give it Defoe’s gloriously clunky full title, Due Preparations for the Plague, as well as for Soul as Body: Being some seasonal THOUGHTS upon the Visible Approach of the present dreadful CONTAGION in France; the properest Measures to prevent it, and the great Work of submitting to it. In this, Defoe makes a distinction between preparations for the plague and preparations against the plague. For Defoe, as for us at this moment in time, the disease was a certainty and people should prepare for it: by stockpiling, by isolating themselves if they are sick, by limiting social contact. Vinegar came into its own as shopkeepers demanded money be dropped into it to clean the coins. I predict a resurgence of vinegar’s popularity. Defoe was a miasmist, thinking the plague spread through foul air, but he observed that people in close quarters became infected more frequently. Then, as now, the poor lived in the closest quarters and died in greater numbers.

The plague of 1722 never became an epidemic and the disease never broke out in epidemic dimensions in Europe again. Defoe was a faulty Cassandra, writing and shouting about an epidemic that never was. He was prolific, writing many articles warning of what was to come. We can only imagine what a pain he would be had he had access to social media. One thing his writing demonstrates for us, though, is that disease is never simply medical. His writing frequently conflates contagion as a physical threat and contagion as a response to sinfulness. Susan Sontag spelt out Defoe’s insight for cancer, for tuberculosis, and for AIDS with her usual incisive brevity: certain diseases lend themselves to metaphor. Cancer and tuberculosis are individualised illnesses. As such, they were seen as expressive of the sufferer’s character. In the nineteenth century the TB patient was frequently thought of as a fragile, creative genius. In the twentieth-century, cancer becomes a source of shame, the seed of death eating away at the sufferer from the inside, often linked to lifestyle. AIDS, like plague and COVID-19, is an affliction of the community and was depicted in the press when it surfaced as a punishment for homosexuality and an affliction of immigrants and drug-users. Infectious diseases are vectors for spurious and deeply damaging moralism aimed at a minority section of society. We have seen some of this already, in Trump’s scapegoating tweet about COVID-19 as the “Chinese disease” and the rise in acts of racism against Asian citizens in the West. All the worst aspects of our society are going to be amplified in the coming days, weeks, and months.

At the same time, these are new times, times where we are going to have time. Families will spend more hours together than they ever have before. The enormous childcare system called schooling which is the lever allowing parents to work has stopped or is about to in countries all over the world. Life will be completely different for all of us during this pandemic and, crucially, after it. COVID-19 is going to show us very starkly how important a free healthcare system is, how shameful the gaps are that people will fall through, how much more we could care about our community and help our neighbours, how crucial so-called “low-skilled” workers like garbage collectors and delivery people are, and how we could restructure our lives, work less, make more. “It is not a time for ideology”, Rishi Sunak, the British Chancellor, said yesterday. He is wrong. At this moment, as we lockdown, we need creative, generous, supportive thinking about how we want to restructure the future. Everything is thinkable. Everything is on the table.