Two giants of revolutionary thought passed from this world in 2018. Through them, we can glimpse the distant shores of a classless society.

They appeared first in Italy, then the UK, then the US – masked protesters carrying shields painted to look like the covers of books. In the wake of the 2008 economic crisis, as politicians and administrators raised university tuitions, students carried these shields while occupying buildings and fighting police in the streets. There were, it is now clear, rules for the selection of a good title. Many a Marxist nerd has chuckled over the winning image of Theodor Adorno’s Negative Dialectics bowling over a riot cop with baton held high. In this case, the wit of the streets titled the actions undertaken by the crowd. In other instances, though, it provided a name for the crowd itself: here Nanni Balestrini’s The Unseen, there Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man. Beyond wit, a good title should be radical and it should be prominent.

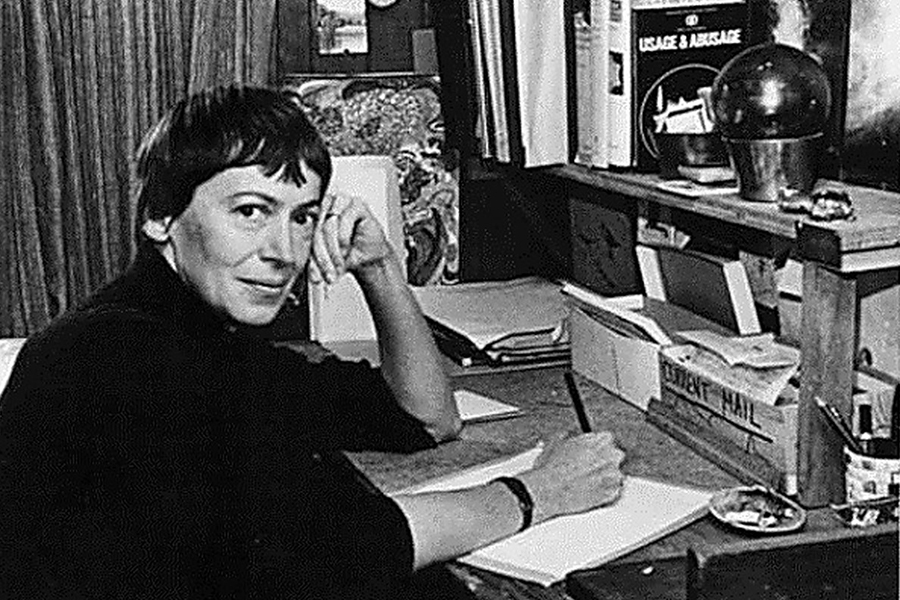

Having your book inducted into such a walking library, used to repel rubber bullets and police batons, is probably as good a measure of political significance as any. That’s why, earlier this year, after I heard the news that Ursula LeGuin had died, the best way I could think to convey the political importance of her work was to share a photo from Oakland, taken in October 2011 during a march organized by the Occupy encampment, in which LeGuin’s novel The Dispossessed strides forward next to Franz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth and Assata Shakur’s Assata, two books radicals I’ve met often cite as formative. LeGuin can, I think, safely claim these writers as peers. The Dispossessed is the greatest utopian novel of the twentieth century, the highest peak in a mountain range of literary achievements.

As its subtitle tells us, The Dispossessed is “an ambiguous utopia.” Readers of the genre, however, will know that ambiguity is the essence of such narratives. Utopias are rarely utopian through and through, rarely straightforward depictions of just, harmonious, egalitarian, or free societies. Thomas More’s Renaissance novel, Utopia, from which the genre takes its name, has puzzled critics for centuries, describing a society that is in some places a satire of political idealism run amok and in others a straightforward depiction of social justice as More imagined it. He coins the word by combining the prefix ou (meaning “not”) with the root topos (for “place”). Utopia is a nonplace, but it sounds the same as the word beginning with eu, eutopia – a good place. Literary writers since More have used the genre to prove by contradiction that utopia is either impossible, absurd, or likely to lead to an even worse society. The quest for the good leads nowhere. Utopias sour on the vine and become dystopian, or so the reactionary narrative goes.

Ambiguity in The Dispossessed functions entirely differently. LeGuin doesn’t deploy it to discredit the utopian impulse but rather to allow it to truly flourish, to become credible in a way no straightforward presentation could. On the world of Anarres, dissidents from its twin planet-moon Urras, have established a society without money or compulsory work, without hunger or homelessness, prisons or police, and where the domination of women by men has vanished entirely. Society on Urras has developed more or less along the lines of earthly capitalism, whereas the Anarresti are anarcho-communists. The book describes them as anarchists, but the world they’ve built, inspired by the writing and practice of an ancient revolutionary named Odo, conforms more or less to the vision of communist anarchists such as Peter Kropotkin, rather than individualist or mutualist anarchists, who rejected collectivity or imagined a continuing role for the market in social life.

There are flaws, however, or ambiguities with the world they’ve built: the Anarresti live an austere rather than abundant communism. Their moon supports only a narrow band of plant life, the atmosphere is thin, the landscape mostly desert. Society there has found its level, a steady state in which there is enough for everyone but only enough, and after a century and a half, a certain rigidity has appeared. Communist principle has, in areas, decayed into knee-jerk moralism while bureaucratic hardening clogs the administrative arteries. The main character, Shevek, a gifted physicist on the verge of a theoretical breakthrough, finds himself stymied not only by his compatriots’ constant injunctions against “egoizing” but also by a central planning mechanism that, even though it matches volunteers with potential jobs, often seems as if it is telling people what to do and where to go without taking into account their life circumstances, their needs, and their desires. Shevek is thwarted by the unchanging world he inhabits.

Our understanding of the novel is deeply informed by realism, which established standards and conventions that even science fiction was forced to adopt. In particular, the realist novel turns upon the development of its central characters, taking its cues from the terrible growth of capitalist society. It purest essence is the bildungsroman, or formation-novel, to translate literally, a narrative that has at its heart the growth, education, and passage into grim maturity of its protagonist. Anarresti society as LeGuin constructs it, however, offers few opportunities for this kind of development. Shevek can only, in this sense, become the novel’s protagonist through a voluntary exile, traveling to Urras to pursue his scientific inquiries.

Development is not only at the heart of the novel form, but is the basis for Karl Marx’s conception of communism. While many revolutionaries of Marx’s time and ours emphasized equality in their depictions of the world to come, Marx himself insisted on the centrality of freedom and, in particular, what he called free development. He is, in this sense, much closer to anarchism than the contemporaries who insisted on the right to work or a fair wage. In Marx’s view, proletarian revolution would produce “a community of freely associated individuals” in which “the free development of each is the precondition of the free development of all.” Equality, he argues in many places, cannot be the goal in any sort of simplistic way, since people have different needs and capacities: equal treatment produces, paradoxically, inequality. We do not have similar expectations for children and adults, for example. Instead of asking everyone to consume or work an equal amount, or in the same way, the equality that matters would be one that gave everyone the same opportunities to freely participate in any activity, to freely take, but most importantly, to freely change and grow. In The Dispossessed, what we see through Shevek’s dissatisfaction is a society in which there is freedom but not quite free development, in which there is equality without the fullness of free access and opportunity that is possible.

“The Dispossessed is the greatest utopian novel of the twentieth century, the highest peak in a mountain range of literary achievements.”

All of this is part of LeGuin’s marvelous sleight-of-hand, catching our eye with the flaws in her imagined society while she pulls from the deck the card of revolution triumphant. In other words, by emphasizing the inadequacies of Anarresti society, LeGuin tricks us into taking as utterly credible a communist society that is, despite everything, already pretty good. She uses ambiguity to defeat the skeptic logics of the utopian genre and render what may be the most convincing portrait of communism in all of literature, a communism that is not only plausible but plausibly improvable.

Schoolchildren are often given Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s phrase “suspension of disbelief” as a simple way to evaluate the success or failure of fantastic literature. Were you lulled into taking for granted the talking dragon and magical elves because of the otherwise “relatable” content? LeGuin should be thought of as doing something similar: effecting a communist suspension of disbelief, a suspension first and foremost of capitalist disbelief in the possibility of communism. To do this, she has to induce disbelief in the institutions of capitalism, to display them not as “how things are” but “how they’ve been made to be.” In an early scene from Shevek’s childhood, for example, he and his friends struggle to grasp the concept of a prison, something they’ve read about in history textbooks but which has no correlate in their universe, since they live in a world where doors are left unlocked and no one is ever prevented from exiting or entering a space. One friend volunteers to be confined, and not only that, volunteers to surrender all choice about the length of time he is confined. Shevek and the others must decide. The effect is not only to denaturalize prison, to expose it as an unnecessary and incomprehensible absurdity, but to remind us that it is the result of free human action, of thousands upon thousands of choices that have been made but could also have been unmade, choices that, ultimately, deprived others of choice. Seen in this light, it becomes easy to imagine things otherwise: let’s play a different game. The children confine their friend in a recess within the concrete foundations for their school, by which LeGuin means to suggest, I think, that this sort of imaginative speculation is the basis for their education and ours. Fully one half of the book concerns Shevek’s travel to Urras, the planet split between a market capitalist society and an authoritarian socialist one. The point of these sections is to render strange the institutions we take for granted, to show them, through Shevek’s eyes, as so much waste and unnecessary suffering.

LeGuin’s science-fiction suspension of disbelief is close to what the great Marxist poet and playwright Bertolt Brecht called “the alienation effect,” which involved rendering strange those everyday objects and institutions taken for granted in capitalism. For Brecht, the alienation effect often means to look at the things of this world as they might appear from the standpoint of a future, communist society. In this light, very little is intelligible. Take, for example, this stanza from his nearly perfect poem, “This Babylonian Confusion”:

The other day I wanted

To tell you cunningly

The story of a wheat speculator in the city of

Chicago. In the middle of what I was saying

My voice suddenly failed me

For I had

Grown aware all at once what an effort

It would cost me to tell

That story to those not yet born

But who will be born and will live

In ages quite different from ours

And, lucky devils, will simply not be able to grasp

What a wheat speculator is

Of the kind we know.

It takes an incredibly flexible mind to imagine our own reality as unimaginable from the vantage of those who live otherwise. This is realism of a very different sort than the one that dominates literary fiction. In a speech LeGuin gave in 2014, after receiving the Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters from the National Book Awards, she describes writers who do this work as “realists of a larger reality.” Noting, in reference to climate change, that “hard times are coming,” she suggests “we will be wanting the voices of writers who can see alternatives to how we live now and can see through our fear-stricken society and its obsessive technologies to other ways of being, and even imagine some real grounds for hope.”

She is, of course, not only calling for a certain type of writing but describing her own work. In her case, part of this ability to imagine alternatives derives from what is a fundamentally anthropological way of thinking about human society. Her father, Alfred Kroeber, worked to develop the discipline of anthropology in the United States, and she spent her childhood surrounded by researchers who insisted, first and foremost, on the great variety of human cultural and social possibilities. The Dispossessed forms, along with dozens of other novels and stories, a shared universe sometimes described as The Hainish Cycle. The Hainish novels and stories describe humanoid civilizations across a number of planets, including Earth, during a period in galactic history when these civilizations are beginning to make contact with each other. Human life on each of these planets is the result of an ancient wave of colonization by the original humans of the planet Hain, whose civilization then collapsed. Further, the Hainish colonists engaged in widespread genetic engineering, such that the resulting societies are incredibly various both biologically and culturally, so various that it is not entirely clear they represent a single species. In the Hainish cycle, one encounters humans who can control their fertility voluntarily, who change sex monthly, who are hermaphroditic, who dream while they are awake, who have cat eyes or bat wings, and who live in societies that are feudal, capitalist, communist, patriarchal, bellicose, peaceful, ecocidal, environmentalist, and dozens of other options besides. LeGuin therefore offers us a speculative galactic anthropology, one in which not only is nothing human alien but in which much of what one might find alien turns out to be human after all. Present earthbound societies are no more the natural form of human life than the finch is the natural form of avian life. In this larger realism, earthbound reality is merely one bird among many.

The libertarian communism of Anarres, however, is not only one among these many forms of human society, but crucial, as it turns out, to the development of the technological means to unite them. The Dispossessed begins at a moment far earlier than the other novels, when the Hainish and the Terrans have made contact with each other, and with the other planets, and have established embassies but have not yet created the galactic associations we encounter in the rest of the books. Travel occurs at near light-speed, but given the constraints induced by relativistic physics, communication must cope with lags of decades if not centuries. Shevek’s scientific breakthrough, which he needed to leave Anarres in order to achieve, occurs in the area of “simultaneous” physics, a modeling of the universe that treats each moment as simultaneous and that, therefore, becomes the basis for instantaneous communication and, eventually, travel. In most of the later novels, instantaneous communication between planets takes place through a device called the ansible. Teleportation, though theoretically possible, has not yet been developed; the planetary civilizations are connected and yet separate. Information flows freely throughout the galaxy, allowing for the establishment of general principles of association – such as non-aggression, free interchange, a basic respect for human life and life generally – but the impossibility of direct transit without relativistic lag means these planetary civilizations develop variously and on their own terms.

Many of the Hainish novels feature main characters who are ambassadors of the emergent intergalactic associations, making contact with human civilizations that have not yet joined. They are observers and diplomats, offering collaboration and assistance, as long as would-be entrants meet certain basic criteria. Some are explicitly anthropologists, and one might wonder to what extent these more or less benevolent characters exculpate a discipline that has never been as neutral and non-colonial in its encounters with other cultures as it imagined itself. LeGuin is clear-seeing about the innumerable forms of caste and class, patriarchy and racialization, that might shape a society, but is also able to imagine a likewise diverse number of societies that dispense with such structures, in part or in whole. Though the baseline of the intergalactic associations is not communism, the most advanced of them do seem to have arrived at something close to it. One might conclude that, for LeGuin, the arc of galactic history tends that way but does so along paths that are divergent rather than convergent. Galactic communism, in other words, would have that variousness and plurality, that openness to development and to the future, which Shevek finds lacking on Anarres.

To make a book shield, one combines layers of hard materials with soft ones. Fiberglass and foam, plywood and polyester stuffing. The structure must be soft enough to absorb a blow from a police baton, yet hard enough not to crumple. The Dispossessed is likewise woven together from layers of dissimilar materials, shuttling back and forth chapter by chapter between the hard class violence of Urras and the soft communalism of Anarres, between the soft luxuriousness of ruling-class Urras and the hard austerity of Anarres, between the hard reality of capitalism as we know it and the soft possibility of the classless society that could be. This is the secret to the book’s success: it makes its utopia real by interweaving it with social forms all of us can recognize, social forms that suddenly, by the moonlight from Anarres, look unreal. What we see, however, is just an image. LeGuin shows us the frozen utopia of Anarres, perhaps, because that is all that literary prose can grasp of utopia, rendering flat and static what must, in fact, be dynamic and living if it will survive. Communism as it develops, communism as it might become, lies beyond all literary representation, since it is not, in fact, a single thing but a vast plurality of developmental arcs, as numerous as the stars of the galaxy. It might last a million years.

__________________________

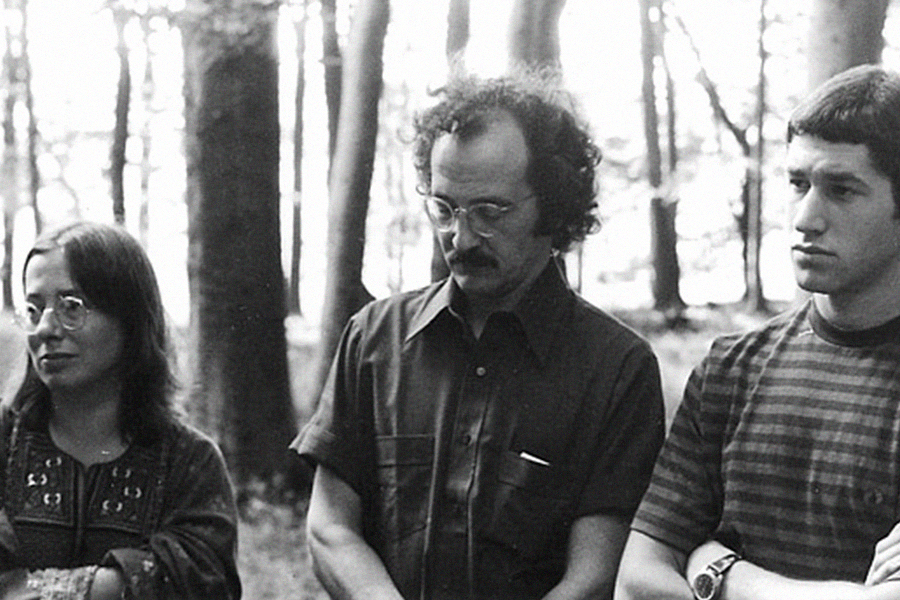

No one made a book shield out of Moishe Postone’s Time, Labor, and Social Domination, but maybe they should have. Postone died this year also, a few months after LeGuin. Like her, he was an otherworldly mind. He only wrote the aforementioned book, along with a handful of articles, but it is a landmark work, easily one of the most important books of Marxist theory written in my lifetime. Along with his teaching at the University of Chicago, this slender corpus has had immense effect on the revival of Marxism since the 2008 crisis and, in particular, has formed part of the essential reading list for a distinctly American version of communist thought.

Both Postone and LeGuin are thinkers whose early work is stamped by the Cold War and the overarching presence of a failed socialism many leftists continued to support, however critically or conditionally. In The Dispossessed, the planet-moon of Urras is divided between an egalitarian but freedomless society and a deeply stratified capitalist one, with political tensions between the two and their proxy wars in smaller states mimicking the long confrontation between the US and USSR as it unfolded in Korea, Cuba, Vietnam, and elsewhere. The Left Hand of Darkness likewise figures authoritarian socialism as one of the directions society takes on the planet Gethen. Postone, for his part, uses TLSD to identify a fundamental error within what he calls “Traditional Marxism,” an error woven into the fabric of socialism as implemented in Russia, China, Cuba, and elsewhere.

Traditional Marxists, Postone argues, misidentified the violence of capitalism with a flawed and unequal system of distribution, failing to develop an adequate critique of production. The problem for traditional Marxists was not, in other words, how capitalism generated wealth but how it spread it around. In the USSR and elsewhere, this error meant that revolutionaries attempted to retain the industrial factory but abolish the market, private property, and profit, replacing those unequal mechanisms of distribution with egalitarian central planning. The project failed, but even if it had succeeded, Postone claims, it would have been woefully inadequate. In the eyes of such Marxists, “socialism is seen as a new mode of politically administering and economically regulating the same industrial mode of production to which capitalism gave rise.” But this leaves traditional Marxists unable to address what people find intolerable about both capitalism and actually-existing socialism. For Postone, Marxism must “develop a critique of the grounds of unfreedom from the standpoint of general human emancipation,” a critique directed at the domination of the factory and production alongside the inequalities of the market and distribution. Rather than proposing to graft a new mode of distribution onto existing structures, an authentically emancipatory Marxist critique would reorganize the entirety of society, seeking out the roots of unfreedom in the material organization of our lives. In this way, Postone lays the groundwork for a critique of capitalism that is more in keeping with the political spirit of the late twentieth century, and particularly the “new social movements” – feminist, antiracist, ecological – which offered a challenge to capitalism no mere reform of distribution could address. Equal pay, for example, may go some distance in addressing racism but is incapable of overcoming the racialized hierarchies of the workplace and social life. In response to the manifest inadequacy of traditional Marxism, Postone aims with no false modesty to reconstruct Marxist theory so that it is adequate to the task it has set for itself.

LeGuin is also very much a thinker of these new social movements, developing visions of human emancipation shaped, at a profound level, by the tumult of the 1960s and 1970s. Her desire to produce a utopia adequate to the desires of these movements is what gives her literary work its maximalist power, driving her to produce in The Dispossessed a glimpse of a classless society beyond the family and patriarchy, beyond the hierarchical logics of race, and beyond the violent norms of heterosexuality. In Postone’s case, the result is a theory that also leaves no aspect of the present world unquestioned. Traditional Marxism, he argues, has made labor the basis rather than the object of its critique, affirming it as a universal aspect of the human condition. A revolution that aims to emancipate labor rather than abolish it will end up perpetuating the proletarian condition. Returning to workers the entirety of the wealth they produce will not end their unfreedom, if this still means that people have no say over the conditions of their own life.

Traditional Marxism finds it impossible to imagine the self-abolition of the proletarian class because it treats labor as a category outside of history, rather than one produced by capitalism itself. By making labor into a category of capitalism, Postone does not mean to make the nonsensical claim that previous societies have never involved labor, but rather that these societies did not conceive of what we call labor as labor, as expressions of an undifferentiated productive capacity. This conception only arises with the general commodification of human activity, once work becomes something bought and sold on the open market. Peasants did not conceive of their work in the fields as fundamentally separate from work in the kitchen garden, from work fixing their domicile, taking care of children, or hunting game. Nor was the line between these activities and play or diversion so firmly drawn. Postone, therefore, attempts to denaturalize and estrange labor in much the same way that LeGuin denaturalizes prison in the passage described previously. Why is it that spending time with a child in one context might be something you do for fun, in another a familial obligation, and in yet another paid work? What would it mean to live in a society in which nothing people did took the form of labor, but merely appeared as a spectrum of voluntary activity, some of it pleasant, some of it tedious, but none of it a job?

This is a useful standard by which to judge the ambiguous utopia of The Dispossessed. The lack of “free development” Shevek experiences is, in part, the result of an opposition between the work he feels called to do – theoretical physics – and work he is expected if not exactly required to do. While no one is forced to work on Anarres – residents can refuse work and still have access to food, housing and everything else, and may even choose to live on their own, as hermits – Shevek and others feel a moral obligation to contribute, given the fragility of life on the planet. They receive assignments from the central planning board that arrive seemingly without much consideration of individual ability and desire. There are weekly rotations of maintenance work that everyone does and which Shevek enjoys, but he resents having to participate in the occasional expeditionary work campaigns that last for months on end, such as when he travels to the driest region to plant trees as part of a geoengineering project. But even on this trip, the resentment mellows and Shevek acknowledges that it is “queer how proud you felt of what you got done this way – all together – what satisfaction it gave.” LeGuin might seem confused or at the least ambivalent on this point. Does the injunction to work arise as part of natural necessity, given by the desert conditions of the planet? Or is it the result of excessive moralism and petrified bureaucracy? Perhaps the book is saying that we can only know what natural necessity is once we’ve gotten rid of moralism and bureaucracy, institutions which preserve, in ghostly form, the opposition between work and non-work that Postone suggests is an impediment to human flourishing. In doing so, both works make it possible to conceive, if only negatively, of truly free development.

The most startlingly original chapters of Postone’s book speak to the question of development, both capitalist and otherwise. Historical development itself, Postone argues, arises only with capitalism. Other human societies underwent processes of change and transformation, to be certain, but only capitalism displays a “directional” dynamic, a sense of history as progress (though as we know this progress rarely means that things get better for most people in any unambiguous way). This is primarily because the organization of capitalist society requires constant increases in the productivity of labor, achieved through the use of new technologies and techniques. This technological transformation becomes the basis for economic growth, which is the form of directional development capitalism recognizes and, in fact, requires. But such development is anything but free. No one chooses it: owners and firms must constantly improve their technology or go out of business. The result is that growth has an “accelerating, boundless, runaway form over which people have no control.”

This unfree development has its origins in a paradox Postone explains lucidly: technology increases the “material wealth” of society massively, constantly expanding the number of commodities which a single worker can generate. What matters for capitalists, however, is not wealth but “value,” which, following Marx, is measured in terms of human labor time. Making workers more productive does not increase labor time, however. If I work eight hours and produce ten times as many goods as I did the day before when I worked eight hours, I’ve still only worked eight hours. Aside from population growth and the lengthening of work days, human labor time never increases, no matter how productive society becomes. Thus in value terms, the process of accumulating more material wealth through increases in productivity leads to no real increase in output. Capitalists, impelled by the market to capture more value, frantically increase productivity but the overall results are moot. The dynamic, therefore, is not one of “progress” but in fact better described as a treadmill. History has a direction, but it does not lead anywhere. The number of commodities produced and the amount of resources used, per person, rises precipitously, corresponding to an ongoing, runaway destruction of the environment, but for the working class very little changes: growth does not result in less work, nor does it mean some gradual progress toward emancipation. The more things change, the more they stay the same.

Postone offers this reading of the underlying “trajectory” of capitalism in order to deepen his critique of those anti-capitalisms that aim merely to re-distribute the fruits of industry. Runaway growth cannot be countered by a change in property relations. Even if workers owned the machinery and received the full share of the product generated by it, as long as they were still compelled to generate constant growth, they would have no effective control over the direction of history and their own lives. The free development of each and all requires an overcoming of the logic of growth, at least inasmuch as growth implies automatic, compelled increases in productivity. Growth, furthermore, depends upon a distinction between work-time and non-work time, as it focuses on the efficiencies of labor to the exclusion of all else. One way to abolish growth, then, would be to overcome the division between work-time and non-work time.

__________________________

Postone and LeGuin chart the locations of the two monsters, Scylla and Charybdis, between which revolution must pass, in order to arrive at the shores of an authentically free and classless society. Postone demonstrates that growth will always mean unfree development, with humans subordinated to an economy that proceeds automatically rather than in accord with their needs; LeGuin, for her part, shows that a steady-state system is no solution, either, as it lacks the dynamism, open-endedness and futurity which people value and desire. We need, then, a development without growth, a history without progress. Shevek, as we know, feels stymied by the unchanging character of Anarrestian communism, and one might think, initially, that he wants something like progress, the passage from one scientific innovation to the next. But his theoretical framework, simultaneism, cuts against such ways of thinking about time. Shevek notes with wry satisfaction that the design for the ansible has been accomplished before Shevek’s necessary theoretical work is complete: “engineers,” he says, are thus “themselves proof of the existence of causal reversibility.” The inventor of the ansible, he continues, “has his effect built before [Shevek has] provided the cause.” It is thus impossible to fit Shevek’s discovery into a narrative of cumulative, successive innovation and technological advancement.

“What would it mean to live in a society in which nothing people did took the form of labor, but merely appeared as a spectrum of voluntary activity, some of it pleasant, some of it tedious, but none of it a job?”

In capitalism, structures of technological advancement are the precondition of development, but in the Hainish universe, those civilizations that have the most powerful technologies use them sparingly, and organize everyday life in a manner that looks, from our perspective, to be highly traditional, based on handicraft, ritual, and religion. In such societies, scientists might spend their mornings building gates with hand tools and their afternoons working on machines for teleportation. The most highly technologically mediated societies, conversely, tend to encounter problems of resource depletion and pollution. Free development for each and all implies voluntary change, but this need not mean a constant technical transformation of the built environment and everyday life. In the Hainish universe, human society has moved in directions that can only be understood, from the standpoint of technological growth, as movement backwards or sideways, branching out in innumerable directions.

Few today believe in progress as an inevitable law of human history. Whereas capitalism could once convince many that the future looked bright, such assurances are now hollow. The future as most imagine it is rising seas and wildfire, refugees at the borders and unemployed in the streets, killer drones and total surveillance. We lack any ability to imagine utopia, ambiguous or otherwise. That’s why we need thinkers like Postone and Le Guin, who show us a future that is not the outgrowth of history but its overcoming, a future that is progress without progress, a future no longer dependent upon the progressivism, productivism, and statism which so many of their contemporaries took for granted. Progress brought with it, for the left, a notion that communism was inevitable. We can no longer rely on such certainties. The most we can say is that it’s possible. This is what Postone and LeGuin show us. Not only what it could be but how.

The book shields of Oakland disappeared for a few weeks after the picture above was taken. But they reappeared briefly the night the police evicted the Occupy Oakland encampment, invading it from all sides, gassing everyone, and arresting the people unlucky enough to get out. Some people grabbed the shields from whichever tent they had been stashed in and crouched behind them, trading projectiles with the police until the situation was hopeless. The shields reappeared again a week later on the night of the “General Strike,” in which the encampments shut down the port and most of the downtown. As darkness fell and the riot began, you’d occasionally see a masked kid crouched behind one of the shields, throwing a rock at an advancing line of police. The books had been absorbed by the collective, and no longer appeared as an orderly front, as the head of a march moving in a certain direction. The riot moved in many directions at once, along many lines of advance, and LeGuin with it. I didn’t see her shield that night, but I knew it could turn up at any moment.