The only cure is to change the world.

For more than three decades, I took part in a variety of one-on-one therapies and group therapies. The aim was for me to share what was on my mind or in my life with a therapist who would respond with suggestions or critiques that would help fix me. Struggling with anorexia and anorexic thinking, I would, for instance, say I was fat. More often than not, I was told I was not fat; then the therapist would ask what I really thought, which was a mystifying question. I had just said what I really thought. From my therapist’s responses, I eventually came to understand that what I thought—I’m fat—was wrong, that the therapist didn’t understand or empathize with me, and that she was growing impatient.

Over the years, I began unconsciously to intuit what the therapist wanted me to say—I would talk, for example, about my specific day-to-day problems, such as what to eat, so the therapist could then feed me the culture’s sanctioned solutions to these problems. I want to be clear: I didn’t know I was doing this. I had so completely absorbed my many therapists’ reactions and responses to me that I had, in a sense, become trained in behaving how they wanted me to behave. Rather than working to discover what was happening below the surface of my reactions, beliefs, and thoughts, and thus gaining access to who I was and then learning to embody this person, I was becoming more and more skilled at intuiting what other people wanted or expected from me and meeting these expectations. What I was learning from my therapists I was also learning from the dominant culture: it was not okay to talk about how I felt about myself and my being in the world.

I often wonder how different our understanding of anorexia would be if the treatment of it were different. As it stands, the main treatment for anorexia is institutionalization, during which patients are subjected to both a series of rules governing them and a structuring of their every hour, beginning at five in the morning with a mandatory weigh in. Imposing such hyper-control and surveillance can’t possibly be a means of healing an illness that by definition originates in hyper-control and hyper-vigilance. This treatment imparts a powerful message: it tells us that anorexics, more often than not girls and young women, are thinking and behaving incorrectly. It asserts that these girls and young women need to be trained through disciplinary force to behave correctly so that they can conform to the culture from which they’ve strayed.

“In this form of nonhierarchical, mutual care, staff did not wear uniforms, duties and responsibilities were shared by every member of the community, and everyone’s input was taken into consideration.”

This style of treatment also has much in common with the way most people suffering from mental illness are treated: they are medicalized by being placed in an institution and/or through the medications they are forced to take, medications with consequential side-effects that influence their day-to-day living and can also shorten their life spans. Further, the anorexic or bipolar, the depressive or anxiety sufferer, is treated by medical professionals who for the most part do not suffer from such illnesses and who speak from the point of view of authority. People with mental illnesses are viewed as if they are an aberration—their doctors or therapists represent what is “normal” and what the patient ought to aim at becoming. In other words, treatment is based on the idea that there is a right way and a wrong way to be, and the treatment offered is rooted in the socially enforced belief that the patient is “wrong” and that her treatment is the means by which she will un-become wrong, will become right. Then she can be seamlessly assimilated into the dominant culture.

____

The Saint-Alban hospital, in the small village of Saint-Alban-sur-Limagnole in central France, was run by François Tosquelles, a Catalan psychiatrist and the creator of Institutional Psychotherapy (IP). Influenced by psychoanalysis and communitarian ideals, Institutional Psychotherapy aims at healing two forms of alienation: the alienation resulting from living with a mental illness and the alienation of living in a capitalist society.

IP came about for a number of reasons. As the historian Camille Robcis explains:

First, [the doctors and medical staff at the hospital] were appalled by the state of psychiatric hospitals during [World War II]. In France, 40,000 psychiatric patients died from food shortage, rationing, and harsh living conditions. As we now know, these deaths were not only due to hunger and cold, but also to a specific policy of extermination geared towards the mentally ill that the Nazi State promoted, and the Vichy regime silently endorsed. Many of the doctors who ended up at Saint-Alban during or right after the war had fled fascism, participated in the Resistance, or been imprisoned in concentration camps. They observed a similar “totalitarian” or “concentrationist” spirit within the psychiatric hospital, refused to be complicit, and called for more humane practice.

At Saint-Alban, everyone’s input mattered in equal measure—Marius Bonnet, a nurse at the hospital, asserted, “everyone on the staff intervened in the system of psychotherapy. If a gardener proposed an idea, a patient would answer him that it was bad. When I think back at this period, I often wonder: in Saint-Alban, who was curing who?” In this form of nonhierarchical, mutual care, staff did not wear uniforms, duties and responsibilities were shared by every member of the community, and everyone’s input was taken into consideration. This egalitarian practice suggests that although, technically, the setting in which the participants find themselves was ostensibly for the healing of the “patients,” in truth, everyone living in the dominant culture had internalized the culture’s desires and ideologies and needed to be “healed” by the ways of being and being together that Saint-Alban offered.

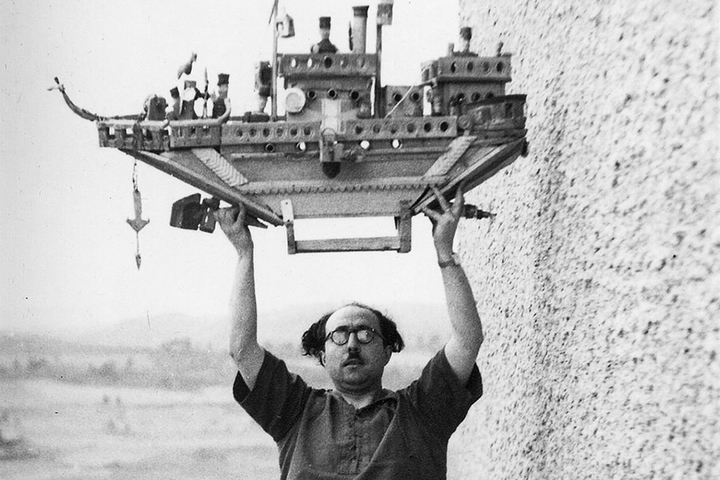

Tosquelles, one of the first members of POUM, a Spanish, Communist, anti-Stalinist political party, fought with the republicans against the fascists before escaping to France, where he was interned in a concentration camp for Spanish refugees. There, he set up communities to help heal the inhabitants of the camp. This work made clear to Tosquelles both that psychiatry could be practiced anywhere and that psychiatric work was intrinsically linked with the critical work of “disoccupying” the mind.

Marx and Freud were crucial figures in Tosquelles’s work. Placing these two thinkers at the core of his thought rooted Tosquelles’s practice in both activism and psychiatry. Indeed, Tosquelles brought two texts with him as he escaped the fascist regime: Jacques Lacan’s 1932 thesis on psychosis, and Hermann Simon’s theory of “more active” therapy based on his psychiatric work in an asylum in Germany. In his work, Simon focused on the importance of patients being active, not so that they are kept busy, as is so often the case in modern psychiatric institutions, but to help patients realize a sense of freedom. As Tosquelles explained, “the point” of providing activities and responsibilities for the patients “was not to ‘make patients work’ to alleviate this or that symptom but, rather, to make the patients and the staff work to cure the institution.” Attempting to cure the institution and not the patient, Tosquelles and Institutional Psychotherapy engage in revolutionary work—they act on their understanding that institutions are microcosms of the culture and communities at large; therefore, to heal the microcosms of a culture is to begin the work of “dis-occupying” an entire culture, healing it from the ways it has been infiltrated by capitalism and power.

During World War II, many artists, thinkers, and activists found a home at Saint-Alban, including psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Jean Oury, who greatly influenced the work of Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari and Frantz Fanon, who utilized a number of the hospital’s principles in his later psychiatric work in Algeria. The idea of a community of activists, thinkers, and artists among the hospital staff and patients was an integral part of the collective, interdisciplinary Saint-Alban experiment. This coming together was accidental rather than planned. The hospital became a haven for those in transit during the war, a refuge for patients and nomadic or exiled artists, writers, and thinkers. Saint-Alban Hospital evolved with the community of creators and thinkers who visited, and this evolution set the tone for the work to come: the creation and maintenance of a communal, collaborative, multidisciplinary, and non-hierarchal haven. This mode of being was carried on into the work of those who transitioned through the hospital, and many aspects of Saint-Alban can be seen in later, similar projects.

Jean Oury, who had interned at Saint-Alban in 1947, went on to found the clinic at La Borde. Oury was born in 1924 and raised in a working-class family in a suburb of Paris. In 1953, he bought the castle Chateau La Borde in Cour-Cheverny, an hour from Paris. Oury planned to open an asylum that, he hoped, would be true to the word’s meaning. Asylum derives from the Latin asylum, “sanctuary,” from the Greek asylon, “refuge.” The term seeking asylum suggests seeking safety from persecution. That Oury bought a chateau and not a hospital, prison, school, or apartment complex is noteworthy. The French word chateau is a “large French country house or castle.” And the word castle derives from the late Old English castel, which means “village” and later, “a large building, typically of the medieval period, fortified against attack with thick walls, battlements, towers, and in many cases a moat.” This idea of an asylum as both village and fortress is particularly apt to the projects of Saint-Alban and La Borde because it suggests both a refuge and a home.

_____

It is strange to me how psychoanalysis, which was foundational at both Saint-Alban and La Borde, has been for the most part shut out of contemporary psychiatric and psychological discourses. Aspects of psychoanalysis, such as the work of Lacan, can still be found in academia, and Freud’s teachings still figure, somewhat, in literature studies. Psychoanalysis is still practiced, but the time commitment it requires, its inevitable slowness and its lack of immediate results, is in stark contrast to the model of efficiency that cognitive and pharmaceutical companies offer. When, for example, I practiced cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) with a CBT therapist, I experienced immediate relief from my thinking. But the intervention was short—the therapy dealt only with my surface symptoms and not with why I had developed these symptoms. When for a period of several years I took anti-depressants to deal with my anxiety, the medication helped, but only with the symptoms of my anxiety. Most notably, I suffered from recurring and severe anxiety whenever I had to teach a class. The anxiety took the form of a pronounced self-consciousness: as I was standing before the class I was aware of myself standing before the class; I was aware of my every movement and word, and, at the same time, I was acutely aware of my fear. It’s true that on the medication I was less anxious, but as time passed and my body became conditioned to the medication, my doctor had to increase my dose to manage my symptoms until we eventually maxed out. As with my CBT therapist, the doctor and I never addressed why I was anxious to begin with.

Short-term, results-based psychological therapies and pharmaceutical therapies have taken precedence in the treatment of both psychosis and neurosis, and they separate and label—they simplify by reduction. They share the basic premise that there is something wrong with the patient, something that can—and should—be fixed quickly. These reductive, dominant therapies are the result of what Herbert Marcuse identifies as the reduction of an individual’s thought processes to desires introjected by the state/capitalism. In One-Dimensional Man, Marcuse describes this shift in terms of language:

[T]he defense laboratories and the executive offices, the governments and the machines, the time-keepers and managers, the efficiency experts and the political beauty parlors (which provide the leaders with the appropriate make-up) speak a different language and, for the time being, they seem to have the last word. It is the word that orders and organizes, that induces people to do, to buy, and to accept.

The language Marcuse identifies is legalistic and mimics the way capitalism commodifies, devours, assimilates, and then reduces everything to a base value. In other words, Marcuse describes the language of calculation and (e)valuation—he asserts how language is used to determine and fix the worth of humans and their lives. When, for example, I am asked where I work or what I’ve published, what I am really being asked is, what is the sum total of my cultural and financial currency? In the culture Marcuse identifies, questions are asked not out of curiosity but rather as inverted declaratives.

The language of this culture is an externalization of a kind of thinking that Marcuse says arises from the “Language of Total Administration,” a thinking reduced to a means of quantifying value: “People depend for their living on bosses and politicians and jobs and neighbors who make them speak and mean as they do; they are compelled by societal necessity, to identify the ‘thing’ (including their own person, mind, feeling) with its functions.”

This language of “Total Administration” is internalized by everyone in the culture it creates and maintains, beginning with children who become obsessed with their individual worth in relation to other children. Self-comparison becomes an intrinsic—though learned—habit of self-improvement as a means of commodifying yourself in all aspects of your life. This consumable language is devoid of resonance, of residue, and it resists metaphor or symbolism. It only assesses and labels or conveys what the culture considers digestible facts. The result is a language consisting of holes in which what cannot be explained in one or two succinct, tagline-like sentences is discarded, forgotten. Thus people and concepts that cannot be easily consumed remain outside the language of culture.

When I show my students a poem that articulates the details of poverty or describes a working-class home, they see nothing. Or, rather, they instinctively see a non-descript home because they have not seen and cannot seem to see the homes of poor or working-class people. They have not seen or heard or read images or accounts or narratives of the working-class or poor, who reside in a culturally sanctioned blind spot. The primary instances of poverty that middle- and upper-class people may be familiar with are from media representation, which tends to mean that people don’t recognize the working class or poor unless they appear as characters they recognize from these representations. This raises the question of linear economic progress, which is the fantasy of capitalism. The contemporary blindness to poverty is not isolated—often when people with materially secure lives in the culture of Total Administration encounter a member of the working class or someone living in poverty, they don’t actually recognize them. I’ve been astounded by how often middle-class people I know say they never see working-class people—and yet they must regularly encounter cab drivers and subway and train workers, postal workers, waitresses, nurses, and nannies. This strange case of not seeing results from the lives and experiences of the working class and poor not being part of the culturally sanctioned language or images of the cultural imaginary, and these cultural absences conveniently erase the working class and poor people as real people who exist in the culture that erases them.

An alternative to the Language of Total Administration, with its fissures and erasures, is a language that is inhabitable or embodied. This is the language of fullness, of complex cross-lines, and grey space. This is a language of different speeds and rhythms, of hesitations and silences that accommodate the movements of a wide range of thinking and speaking. This language is the language of La Borde and Saint-Alban. It includes everyone and everything. It listens to everyone, taking in everyone’s point of view and input with equal measure.

_____

At La Borde, patients had free rein of the chateau as well as the grounds; they were able to walk anywhere, exploring as they wished. This freedom of movement is of extreme importance—psychiatric wards and hospitals are by definition institutional, sharing more in common with prisons and locked psychiatric facilities than with Saint-Alban and La Borde, which are essentially communities. As at Saint-Alban, the patients at La Borde shared responsibilities with the staff and participated in communal meetings. Felix Guattari, who was invited by Oury to serve as co-director, created what was called “the grid,” a system that allowed for everyone’s duties and responsibilities to be switched at random. The patients participated in the running of La Borde, the staff drew blood and performed other duties usually performed the doctors and nurses, and the doctors and nurses washed dishes. The objective of the clinic was not to “cure” the patient but to encourage each individual to participate in her own self-creation as if she were an artist.

In 1996 the filmmaker Nicolas Philbert made a beautiful documentary of La Borde titled Every Little Thing. What is most striking to me about the film is the inability to discern the patients from the staff. In fact, like all the staff, Guattari lived at La Borde with his wife, their daughter, and their two sons. The space given to the patients—to walk wherever they wished, to take on a multitude of jobs of various hierarchical values—was a space also given to the doctors, nurses, and other staff, and as I watched people moving through the space of La Borde and its grounds, I recognized that space is necessary to move and think and, ultimately, heal. In our current world, space is a luxury, and it is not afforded the poor, the migrant, the incarcerated, the elderly, and the sick.

La Borde was based on the principle that psychotics cannot be treated until the entire infrastructure of psychiatry is changed. For Guattari, the goal of Institutional Psychotherapy was to learn alongside the patients a new way of relating to the world. In essence, La Borde was a mutual think-tank, a community of learning. In “La Borde: A Clinic Unlike Any Other,” Guattari wrote:

It was then that I learned about psychosis and the impact that institutional work could have on it. These two aspects are profoundly interconnected, because psychotic traits are essentially disfigured in the context of traditional prison systems. Psychosis shows its true face only in a collective life developed around it within appropriate institutions, a face that is certainly not one of strangeness or violence, as one all too often believes, but one of a different relation to the world.

Guattari’s idea is both refreshing and profound. He suggests that when a person experiences psychosis, her psychosis changes according to her surroundings and, therefore, treating her with fear by locking her up, keeping her in restraints, overmedicating her, and exposing her to other methods of suppression only serves to change her psychosis to a psychosis of fear and paranoia. Who, psychotic or not, in the same situation wouldn’t also feel terror and paranoia? Indeed, there is a legitimate reason to be paranoid and afraid. Further, the shock of being treated inhumanly, the sense of alienation and of betrayal, and, perhaps paramountly, the realization that humans can and do treat other humans in this way, is itself shocking and traumatizing. It is a shock and trauma that alters the psyche, changing the personality of the person who undergoes it. Conversely, Guattari saw that giving that same patient space—both psychic and mental and physical space—and refusing to oppress her through traditional forms of psychiatric treatment, changes her psychosis once again. Guittari recognizes the person with psychosis and relates to her as one person recognizing another, rather than as a figure of authority imposing his power on a patient. And through this recognition, Guattari shows the patient that he perceives she has a different way of experiencing the world, without suggesting to her that her way is inferior to his or to the dominant, culturally accepted forms of experience and experiencing.

Guattari makes explicit the connection between labeling patients and then, based on these labels, segregating variously labeled groups from one another in a hierarchical system. He writes:

Unfortunately, in France and many other countries, official orientation is toward reinforcing segregation: the chronically ill are placed in establishments for the “long-term,” which means, in fact, leaving them to crouch in isolation and inactivity; acute cases get special services as do alcoholics, drug users, Alzheimer’s patients, etc. Our experience at La Borde has shown us, on the contrary, that a mixture of different nosographic categories and regular encounters between different age groups could constitute nonnegligible therapeutic vectors. Segregative attitudes form a whole: those one encounters among mental illnesses; those that isolate the mentally ill from the “normal” world; those one finds with respect to “problem children”; those that relegate the old to a sort of geriatric ghetto all participate in the same continuum where one finds racism, xenophobia, and the rejection of cultural and existential differences.

Guattari did not believe, as did some others from the anti-psychiatry movement with which he was affiliated, that mental illnesses were a myth; rather, he argued that the power structures inherent in the way psychiatry is practiced in the West are problematic due to their tendencies toward oppression, and that these forms of oppression are detrimental to patients. During Guattari’s lifetime, oppressive treatments included electro-shock therapy, insulin coma therapy, and brain lobotomies. Current oppressive treatments include over-medication, the use of medication to subdue patients, restraints, solitary confinement, and forced hospitalizations. In addition, adults are given “time outs” and are punished by having their “privileges” revoked. The power structure inherent in the treatment of the mentally ill, with its tendency toward infantilization, is also detrimental to patients.

____

La Borde is still open today. And its history and ongoing work lead me to ask questions about the one-on-one and group therapies I have undergone: What if I had simply been listened to? What if I could have spoken my mind, said my thoughts aloud, without fear of offending or shocking my listeners? What if I had been encouraged to develop my own language for my experiences of being in the world? What if, instead of someone paid to “fix” me, I had had a witness and a place in which to say anything I wanted, and when I said something that was particularly odd or surprising or contradictory or seemingly new in my own language—which is not the same as my culture’s language—the listener made a comment, a comment that did not submerge my words or otherwise make me feel erased? What if this particularity was not erased but instead was illuminated?

For the last two years I’ve been in psychoanalysis, the foundational therapy at Saint-Alban and La Borde, and the experience has led me to a language and thinking that resists the “Language of Total Administration.” This resistance is precisely the power Tosquelles saw in psychoanalysis: it offers a means to undo the damage done to our thinking and our psyches as a result of living in the post-war era that was rapidly transforming into a capitalist culture. As Marcuse points out, when you live in such a culture, it’s difficult, if not impossible, to discern the difference between your own desires and the desires introjected into you by your culture. We are structured through the “Language of Total Administration” and the desires it allows us to articulate and meet.

From psychoanalysis’s beginning, Freud’s main interest was rooted in the idea of repression—psychoanalysis offers a means to access what is being repressed, both on an individual level and a cultural one. In other words, psychoanalysis provides a means to remove cultural ideologies and desires, or what Marcuse calls “false needs,” from the unconscious. Marcuse writes:

We may distinguish both true and false needs. “False” are those which are superimposed upon the individual by particular social interests in his repression: the needs which perpetuate toil, aggression, misery, and injustice. Their satisfaction might be most gratifying to the individual, but this happiness is not a condition which has to be maintained and protected if it serves to arrest the development of the ability (his own and others) to recognize the disease of the whole and grasp the chances of curing the disease. The result then is euphoria in unhappiness. Most of the prevailing needs to relax, to have fun, to behave and consume in accordance with the advertisements, to love and hate what others love and hate, belong to this category of false needs.

It’s interesting to me that false needs include the “needs to relax, to have fun,” as well as the need to “hate” what others hate. What troubles me is that we behave and think according to rules and structures. And yet, these values and ideologies are not “natural” or innate but, rather, have been created and then introjected into us. That these dictates remain invisible to us—that we can no longer discern what desires or beliefs are ours and which belong to other people or institutions—is deeply disconcerting.

Marcuse argues that the antidote is twofold: first, we must be aware of the introjection and repression of these “false” needs; and second, we must replace them with “true” needs:

All liberation depends on the consciousness of servitude, and the emergence of this consciousness is always hampered by the predominance of needs and satisfactions which, to a great extent, have become the individual’s own. The process always replaces one system of conditioning with another; the optimum goal is the replacement of false needs by true ones, the abandonment of repressive satisfaction.

Lacanian psychoanalysis, in particular, provides a means to liberate ourselves—our minds—from desires and ideologies introjected into us from the outside. To begin with, as Samo Tomšič asserts in The Capitalist Unconscious, “Lacan maintained that, in relation to his audience and to the analytic community, he assumed the position of the analysand.” In psychoanalysis, the analysand is the patient, the one undergoing analysis, and the analyst is the therapist, the one helping the analysand through the process of her analysis. The words analyst and analysand sound and look similar, and this is not a mistake. The work of the analyst and the analysand is collaborative—the two are a team. This stance differs markedly from the more common role of the therapist as an authority figure, giving out his clinical interpretations of the patient to the patient. The non-psychoanalytic psychiatrist is a doctor who diagnoses the ill patient and fixes her through prescriptive therapeutic means that the doctor determines. This power dynamic can also occur in psychoanalysis, but an awareness about its potential to occur and steps to remedy its occurrence are part of the psychoanalytic process.

In a Lacanian psychoanalytic relationship, the analysand speaks, verbalizing whatever comes into her mind, and the analyst makes punctuations or small interruptions, akin to gaps or ruptures, in response to her speaking. Lacan believed that the analyst cannot translate the analysand’s words and that any punctuation from the analyst ought only function through “cuts”—questions or small comments where the analyst notes a place of tension or a slip that may have occurred in the analysand’s stream of consciousness narration.

In my own analysis, these “cuts” occur only a few times during a forty-five-minute session and serve to make me engage in what I call a “turn.” When, for example, I make a “slip,” saying one word when I (think I) mean an altogether different one, my analyst might repeat the word to “underline” or otherwise mark it. Through this marking, I’m able to see a small break in a narrative that I’d become so accustomed to that I was no longer able to see my way out of it. This “small break” is a slip my unconscious is trying to communicate to me. By punctuating moments where these slips appear in my speech and in my thinking, my analyst helps me to recognize them as they occur.

These slips occur all the time, not just in my analysis. A week or so ago I was early for my psychoanalytic appointment, so I chose to walk a block out of my way to pass time. When I came to the street of my analyst’s office, I was surprised to find construction where just a few days before there had been none. When I arrived at the building that houses my analyst’s office, I was confused. It was the correct number—9—but the building before me wasn’t his building. I felt fear: If this wasn’t his office, where was it? Then I felt confusion: If this isn’t his office, where is it? I stood before the building for a moment or two until it occurred to me that I was on the wrong street. I was on 3rd Street, and I was certain his office was on this street. I was running out of time, so I went with my intuition, which said his office must be on 5th Street, and when I arrived at number 9 on 5th Street, his office was before me.

The next session, as I was stepping out of the subway station, I noticed I’d received a voicemail from my analyst. When I listened to it, I heard him asking if everything was all right. He explained that he was waiting in his office, that it was already 6:38 p.m. I realized immediately my mistake. Though I’d been certain my appointment was at 7 p.m., certain my appointment was at 7 p.m. every Monday evening, it wasn’t. It never had been. It was always at six. During my next session, I wondered out loud about these instances of being lost. I thought aloud not in an attempt to “fix” the problem of my lateness or to come to a certain conclusion about why I had gotten lost. During the session, as I was allowing myself this playful relation to language, my analyst said, “You feel dislocated?” When he said “dislocated,” the word simply fit. And yet, “dislocated” only points to the enigmatic quality of what happened and what continues to unfold. His suggestion was neither an attempt at a solution nor at labeling but, rather, a diversion, a new direction that spoke to me and that I wanted to pursue.

The closest analogy to psychoanalysis that I can think of is writing. When I write, I type what I’m thinking. And in this way, I find what I mean. I think not finding my analyst’s office when I know exactly where it is was a cut or glitch in my own psyche: some part of me, a part inaccessible to me, was sending me a message. The message was something about nomadism and homelessness—about feeling “dislocated” in the world. The confusions I experienced might be read as commentary on my analysis in general, which is to say my life in general: I feel dislocated and I’m trying to find my home.

As a mute child and an adult who has internalized the cultural directive to keep quiet and not to speak up, psychoanalysis and the regular practice of thinking out loud for the past two years have altered my psyche in ways I am only now beginning to recognize. I am bringing thinking and the intellect into my body by putting my thoughts, as they arrive in my head, immediately into words. Speaking freely whatever comes to mind in an environment where whatever I say remains unjudged and not reacted to allows me to speak myself into being.

One concrete result of this practice is that I am now more able to speak in my daily life. When I was speechless in the second grade and the teacher yelled at me to speak, I couldn’t because I was filled with terror. In psychoanalysis, my words, words that are usually trapped inside my head or throat, are encouraged. However I speak is fine. I tend to think in complex sentences and this, then, is how the words come out of my mouth. Speaking in analysis has revealed to me that outside of analysis I am essentially afraid of speaking and of being while I speak. And when I’m placed in a situation where I feel scrutinized, where I feel I’m expected to make mistakes, that I am being watched for mistakes, I tend to unravel. My grammar breaks down. In psychoanalysis, by contrast, my language is embodied. As a result, I am able to work through finding the best word for experiences I previously was unable to articulate. It is messy, obsessive, and animated. My speaking in analysis is my mind at work: free of judgment and the fear of being corrected, fixed, or otherwise “improved.” Over time this practice teaches me that my mind, and thus myself, is mine. Mine to mold, mine to use, and mine to protect.

_____

“Thinking out loud,” the very premise of psychoanalysis, is, indeed, a necessary practice for thinking critically or even thinking at all. Hannah Arendt argues in The Life of the Mind that “the active way of life is ‘laborious,’ the contemplative way is sheer quietness; the active one goes on in public, the contemplative one in the ‘desert.’” These meditations arose from Arendt’s experience witnessing the Adolf Eichmann trial, the trail in Jerusalem of the former Nazi responsible for, among other crimes, the mass deportation of Jews from across Europe to concentration camps. After attending the trials and reporting on them for the New Yorker magazine, Arendt concluded that “There was no sign in [Eichmann] of firm ideological convictions or of specific evil motives, and the only notable characteristic one could detect in his past behavior during the trial and throughout the pre-trial police examination was something entirely negative: it was not stupidity but thoughtlessness.” This experience and the conclusions Arendt drew by thinking about it led to her considerations of thinking itself: What is thinking? Where are we when we engage in the practice of thinking? What happens when we do not think, when we do not actively pursue a life of the mind?

Tosquelles’s own experience living in a concentration camp illuminated the connections between fascism, totalitarianism, and the mind, influencing his work at Saint-Alban. Describing this connection, Robcis writes of Saint-Alban during the war:

The staff, the nuns, and the doctors who worked at Saint-Alban sought to subsist and feed their patients by hoarding extra food with the help of the local population. Alongside the efforts to secure nourishment, various doctors at Saint-Alban began to question and rethink the practice and theoretical bases of psychiatric care. As the war and fascism had made particularly evident, occupation was not just a physical condition: it was also a state of mind.

The result of Saint-Alban—the hospital as experimental site of healing that forwent hierarchies and preconceived beliefs—planted the seed of revolutionary thought in the work of those who participated, and proved that the assumed need to segregate those who could not or would not adhere to cultural norms was a faulty one. The importance of breaking down walls, both figuratively and literally, was paramount in the work of de-occupying the body and mind.

Originally published in Disquieting: Essays on Silence (Book*hug, 2019). We are grateful to Book*hug for permission to reprint.