The Oakland teachers’ strike fell short of some of its goals. To win it all, the new labor movement will have to get bigger, wilder, and more ambitious.

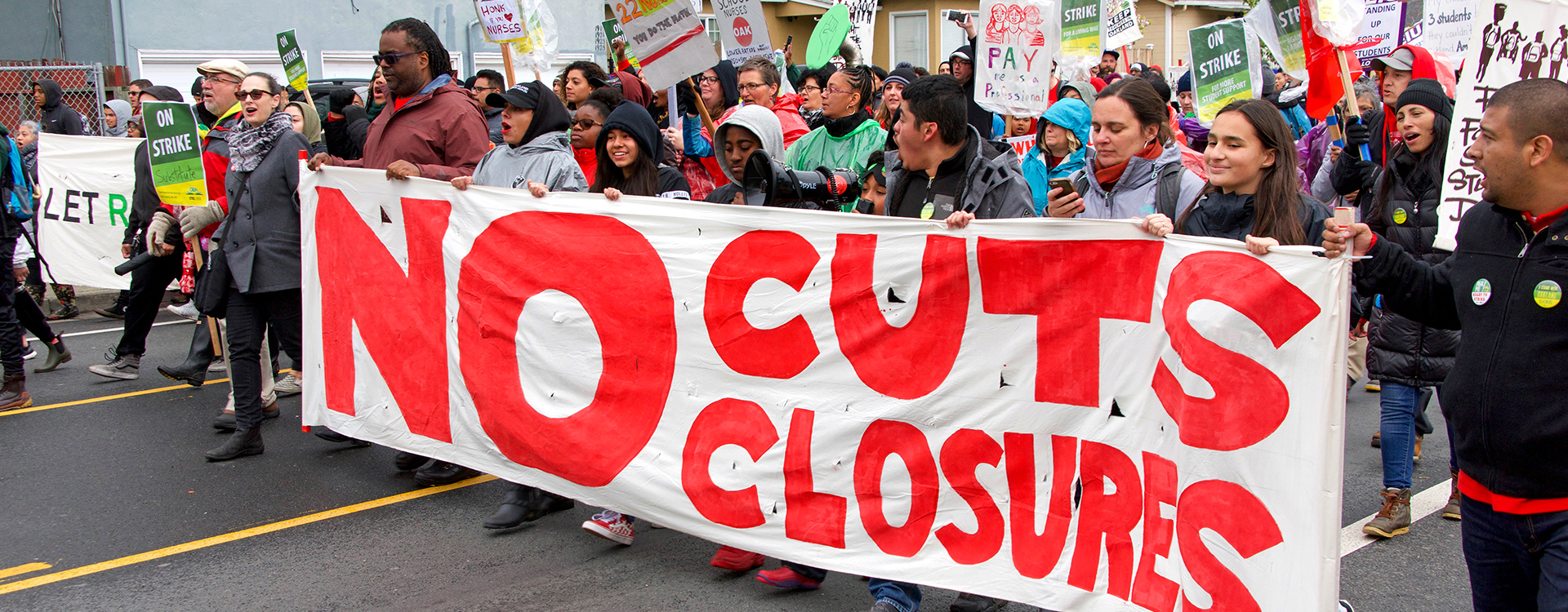

Oakland is the latest city to be hit by the wave of teachers’ strikes sweeping across the country. The strike in Oakland came to an end on Sunday with an ambiguous victory. A contract that fell short of expectations was approved by just 58 percent of the union membership. The strike raises a number of important questions about the relationship between the union and self-organization, between political demands and political power, and between victory and defeat that will likely come up again as the teachers strike wave continues.

Evaluating the Deal

Although the Oakland Education Association (OEA) declared the new contract a “historic victory,” 42 percent of teachers voted against it. Even among those who voted for it, many dislike the contract but worried that a continued strike might lack community support. What about the contract disappoints so many teachers? It falls short on each of three central demands.

First, it only includes a five-month moratorium on school closures. The Oakland school district still plans to close twenty-four of its eighty-six schools; a first step toward replacing public schools with private charters. A five-month moratorium barely covers the remainder of the current school year. In other words, it’s a symbolic gesture.

Second, the wage increase is modest. The contract gives teachers an eleven percent raise over four years, with most of the pay increases coming in the later years. In the Bay Area, where cost of living has been increasing by more than 4 percent a year, this raise still amounts to a pay cut in real terms. The union had initially demanded a 12 percent raise over three years.

Third, the contract decreases class sizes and increases the number of nurses and other support staff per student, but not by as much as teachers had desired.

If the strike had been faltering, this deal might have looked good. But the opposite was happening. Teachers were still participating en masse, student attendance during the strike hovered at nearly five percent, and there were plans to shut down the Oakland port in the coming week. The strike was still intensifying.

Independence of the Site Representatives

The OEA’s ability to coordinate community support and distribute information and supplies was immensely significant for the initial strength of the strike. At first, the union kept the teachers energized and encouraged them to take initiative. Over the course of the strike, though, the OEA’s role began to reverse, and by the end, the union was practically at odds with the teachers’ organization and drive.

As the strike developed, a new form of teacher self-organization emerged from within the union. At the daily meetings of the site representatives, or “site-reps”—one hundred twenty teachers who each represented about fifteen other teachers from their respective schools—began to guide the strategy of the strike independently of the union leadership.

At first, the site-reps simply approved more militant picketing tactics, which included a blockade of the central kitchen responsible for food distribution to all Oakland public schools. By the sixth day of the strike, they were coordinating a shutdown of the port. One teacher asked whether they needed the approval of the union leadership for this. The consensus: because the site-reps directly represent every teacher in the union, they are the union, and can take decisions independently.

The relationship between the site-reps and OEA leadership remained friendly—and for good reason. The teachers were escalating tactics without the legal or bureaucratic restrictions of the union, and the union was providing the structured support necessary for the day-to-day continuation of the strike. The relationship, at this point, was mutually beneficial.

It wouldn’t break down until the union leadership announced a tentative agreement with the district.

Blockading the School Board

On Friday, a week into the strike, about 3,000 teachers and supporters shut down a school board meeting that was expected to approve $22 million in budget cuts. Picket lines blockaded each of the twenty entrances to the building the meeting was to take place in. Right as board members began to arrive and attempted to enter the meeting, the union announced a tentative agreement with the district. Numerous officials in yellow vests encouraged the picketers to disperse and head to a press conference.

Then the unexpected happened. Some teachers did leave, but not one of the twenty picket lines dispersed. Every single one, independently, decided to continue holding the line. Board members were heckled and pushed from the site. One board member choked a teacher. A board members’ bodyguard fought with picketers. Many of the OEA officials wandered around looking befuddled. It was now a wildcat action.

Until this point, the pickets had largely stayed on the sidewalks. Now, they blocked traffic on the four intersections surrounding the meeting site, which covered a large block. Discussions took place in the streets, as teachers talked over the details of the proposed agreement. The consensus was clear, at least among those present: this agreement will not do.

By breaking with the union, at least for that afternoon, the strike transformed into something more powerful, more disruptive, and more encompassing. Students and workers from other unions articulated their demands alongside those of the teachers. It’s not clear whether or how this emergent dynamic would have persisted into the next week, had the strike continued.

With a Vote, the Strike Ends

The tentative agreement that was dismissed on the ground on Friday became a fact in the next morning’s news cycle. On social media, and to the community at large, the OEA proclaimed a victory two days before teachers actually voted on the contract. This left the teachers in a conundrum: after the OEA had already assured volunteers, parents, and students that every demand was won, how would they respond to a continuation of the strike? Would there still be the same popular support now that their own union had declared the important issues settled? The OEA, by declaring victory, surrendered the moral high ground the teachers had stood on, and they did so before the teachers themselves could weigh in on the contract.

The day before the vote, the site-reps met to discuss all that had happened. Only a handful of teachers actually supported the deal, but many worried that support for the strike would wane if they rejected it, particularly since victory had already been declared. This fear split the site-reps, who ended up supporting the deal by a narrow margin of fifty-three votes in favor to fifty against. Many teachers tried to organize for a “No” vote, particularly those from West and East Oakland who were most likely to see their schools closed before the contract benefits would materialize. When the official vote came on Sunday, the margin had expanded: 58 percent voted in favor of the deal.

Importance of Political Demands

The political character of the teachers strike wave distinguishes it from standard “bread and butter” strikes. Across the country, teachers have fought for more than their own immediate interests. Yes, they fought for higher wages and the preservation of their jobs. But they also fought for a vision of public education that serves the public. They demanded an education system that challenges racism. They picketed to keep more schools open across the city; for smaller class sizes, for greater access to schools. Through these demands, the teachers spoke to the city as a whole and drew the entire community into their fight. And it is the broader political aspects of the struggle that helped galvanize the teachers themselves, giving their strike a meaning and intensity it may have otherwise lacked.

That these strikes raise political demands also means they raise the question of political power. To achieve renewed investment in public schools or an end to private charters requires the exertion of power on the level of state and local governments. Striking teachers in Oakland may be able to stop plans to privatize Oakland schools, but can they increase state funding to the district, or win a statewide moratorium on charter schools? Yes and no. For West Virginia teachers, a statewide strike has become a political reflex. This has allowed them to have the upper hand in decisions made by the state government. Though a similar forcefulness is possible in California, teachers have a lot of work to do in order to make this the case. A strike confined to within a particular district, and limited to a contract negotiation, can’t achieve this type of political influence.

Within Oakland, however, a teachers strike can and did assert some political power. Teachers demanded an end to school closures, a demand that would normally fall outside the realm of negotiations. Teachers may have only won a symbolic concession, the five-month moratorium on closures, but even that concession shows that the broader political issue was at least on the table. As teachers head back to their classrooms, the fight against school closures continues. It’s not clear yet how it will play out, but one possible trajectory can be seen in the fight against school board budget cuts.

The school board meeting that was prevented from taking place during the strike was rescheduled for the day after the strike ended. The meeting was not shut down this time, and the school board proceeded with the planned budget cuts. The very contract that teachers had just won was used by the board to justify cuts made to other staff and to student programs. Many students and teachers spoke out against the cuts, but this didn’t stop the board from adopting them. If on Friday, during the single most intense moments of the strike, a new way of doing politics had seemed to emerge, by Monday, the energy of the strike was channeled back into the everyday working of politics.

What Will the Teachers’ Strike Leave Behind?

To learn from the strike, we should try to understand it in all its hopes and contradictions. The OEA both provided the necessary foundation for the strike and, in the end, limited it. The spirit of the union, embodied in the site-reps, at first depended on and then conflicted with the OEA leadership. The strike initiated new ways of organizing and new forms of power, but their persistence beyond the strike is as of yet uncertain.

The strike is over, and it leaves behind a contract, a more solid union, and more political will against the privatization of public education. These accomplishments, though, don’t just accumulate—they have to be fought for again and again, and the normal working of politics causes them to decay. Beyond this, the strike points toward the possibility of teachers becoming a new political force, able to exert the power of the strike to win demands outside the bounds of contract negotiations. How can we lay the foundations to build such a political force in a way that, over the course of struggle, won’t end up limiting our self-organization? As this new power emerges, how can teachers maintain and expand it? These are the questions posed by the Oakland teachers strike.