Self-organization in the sagebrush, a romance.

Today in Sarsaparilla, Nevada, there would be a duel. The church bells were ringing. The skies had thundered the night before, soaking the ground with rain, so that Randy’s boots made wet suckling sounds in the soft mud as he strutted into place for the duel.

Randy Steel rested his thumb on the buckle of his brand new gun belt as he took up his spot on Main Street. The fine leather of the gun belt was itself a thing of beauty, but the buckle its true marvel: a gold, five-pointed star soldered onto an engraved silver backdrop. Randy shined it every morning to better enjoy his own reflection, taking it as a sign of his prowess as a bounty hunter.

Randy was in town because of a letter the town’s silver mine boss had sent him. The mining company had been having trouble with a redheaded firebrand of a woman by the name of Big Bad Butch Dynamite stealing payroll shipments; the boss said the company’s owner had pledged a not-trivial part of his considerable fortune to the man who could bring her in. Randy was in Sarsaparilla to collect that bounty.

If Randy were a smarter man, he might’ve noticed when he’d got to town that no one appeared to be wanting for their supposed backpay. In fact, there was a gaggle of miners outside the general store smoking fine North Carolina tobacco, which he knew didn’t run cheap this far west. Some of the miners even had belt buckles rivaling his own. But he was never one to put two and two together. Instead of pondering, he stepped into the saloon, hoping for whiskey, a woman, and maybe a lead on the whereabouts of Butch Dynamite to follow up on in the morning.

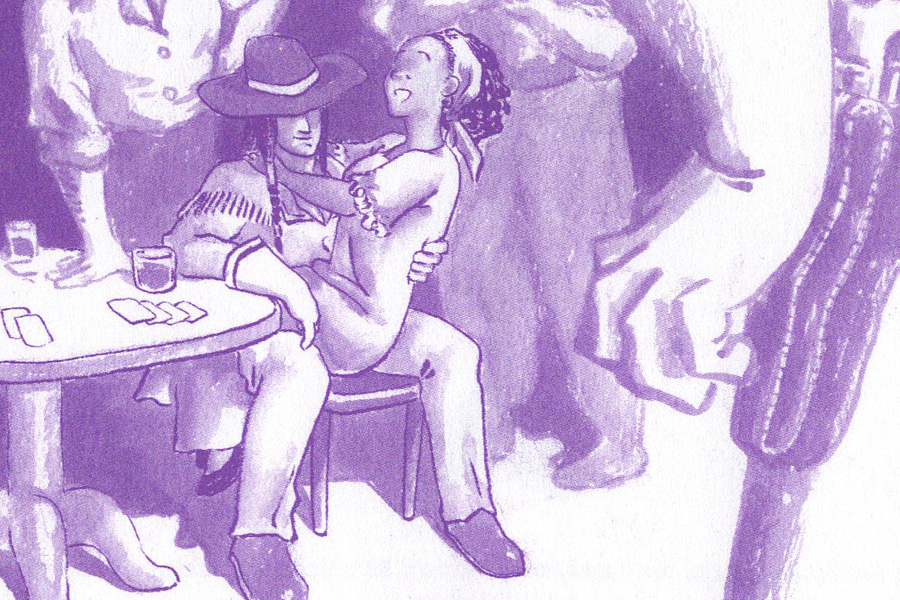

But once his eyes adjusted to the dark, there, at a card table full of gruff-looking ne’er-do-wells, sat Big Bad Butch Dynamite laying down a full house, a miner’s daughter in her lap. She was wanted for rustling, debauchery, public drunkenness, vagrancy, arson, sodomy, and the suspected murder of thirteen missing mission priests no one really seemed to miss at all. Butch looked up from her cards, a smoke hanging from her lip as effortlessly as a linen shirt on a line in a spring breeze. No man had seen fit to call her beautiful, and no man was fool enough to call her handsome — though word had it several women had done so quite successfully.

“Well, there you are, Randy,” she greeted him. “Have some trouble coming up through the foothills, partner? The Sierra Nevadas ain’t much made for flatlanders from Texas.”

Randy’s mouth hung open as he tried to put a sentence together. His blood boiled up and he moved in to arrest here then and there. But the miner’s daughter — looking like a fluffy mountain bluebird in her pale cornflower-colored dress, but with a bouquet of tight curls held back in a silk scarf — laughed and slapped her knee loud enough to be heard all the way to Cincinnati.

The young lady’s cackling made Randy blush, though he didn’t know if it was for the sake of her impropriety or his own embarrassment. Whatever it was, it made him stumble and he missed his chance. Then, Butch spoke.

“Don’t bother saying anything because we all know why you’re here and that you’re not exactly the brightest star in the sky,” she commanded. “You are a law man, after all. And yet I know you by reputation as a man of as much honor as any law man can manage. Now, I know you’re here to kill me, but I’m asking you a favor and I’m going to appeal to your sense of mercy if’n you got one.” The miner’s daughter held a sly, half-cocked smile as she stroked Butch’s hair, making eye contact that kept Randy unnerved.

“Let me have this night to savor, a final fruit before you turn me into plant food, bounty hunter,” Butch said. “All’s I’m sayin’ is, you get paid if you bring me in dead or alive, and you’re not bringin’ me in alive — and on top’a that, my friends here ain’t the fair-fightin’ types, neither.”

“So just give me this night, and then how’s about you show me if that fancy gun belt of yours,” she pointed at his crotch, “is just for show.” Randy looked down at his belt then back at Butch. “Meet me on Main Street when the church bells toll high noon,” she bade him.

Randy agreed, sensing both an opportunity and a threat. He’d much rather take on Butch one-on-one in the street than in a barroom brawl. He’d won a dozen duels in his day, and he was sure he could win another, especially if she had a night of hard drinking and lovemaking ahead. And, hell’s bells, it felt strange enough trying to apprehend a woman who refused to come peacefully, so a duel did offer a compromise with honor, so long as he left town with the body that’d get him paid.

_____

There he was — hand at his hip, boots in the mud, narrowing his eyes as the echo of the church bell’s final peal lifted away through the air like the steam off a stew pot. Butch held his gaze, half a smile cocked across her face.

Randy went for his gun. But in place of the familiar pearl handle, he heard a crack like a wagon axle snapping in place. His gun belt, six-shooter and all, dropped into the mud around his boots. His dungarees were still held in place by his non-gun belt, but Randy couldn’t help but feel as if he’d just dropped his britches around his ankles. Not that he’d never know it, but when he went for his gun, a bad weld on the back of his prized belt buckle had snapped, corroded as it was by the polish Randy used dutifully each morning.

Butch clucked her tongue and said, “Bless your heart.” Then, she shot him twice straight through the very organ she’d just sanctified.

Randy Steel was dead before he hit the ground.

_____

Because he died, he’d never learn that those brutes who’d been with Butch in the saloon weren’t her gang and they weren’t even playing poker. They were members of the miners council hosting a meeting to determine their next plan of action. And he would never know, though he might’ve guessed from that fine tobacco he smelled, that the miners’ and their families were still getting paid despite the quote-unquote missing payroll. Nor would he ever hear tell of Alma Freeman — the same miner’s daughter who had been sitting on Butch’s lap that night in the saloon — or the speech she gave that wiped the name of Sarsaparilla from the map.

Alma’s daddy had settled in the land that would become Sarsaparilla long before the mining had started and a little after he ran out of the South with his freedom. She’d grown up there alongside the mine, and all her life she’d seen clear streams turn nasty and watched the quails disappear — lately, she’d even noticed the sagebrush was taking on a funny brown color. The nearby tribe had tried to warn the town of what they were doing to the land, but the mine meant there were jobs, and even her daddy had taken one, miserable as it was.

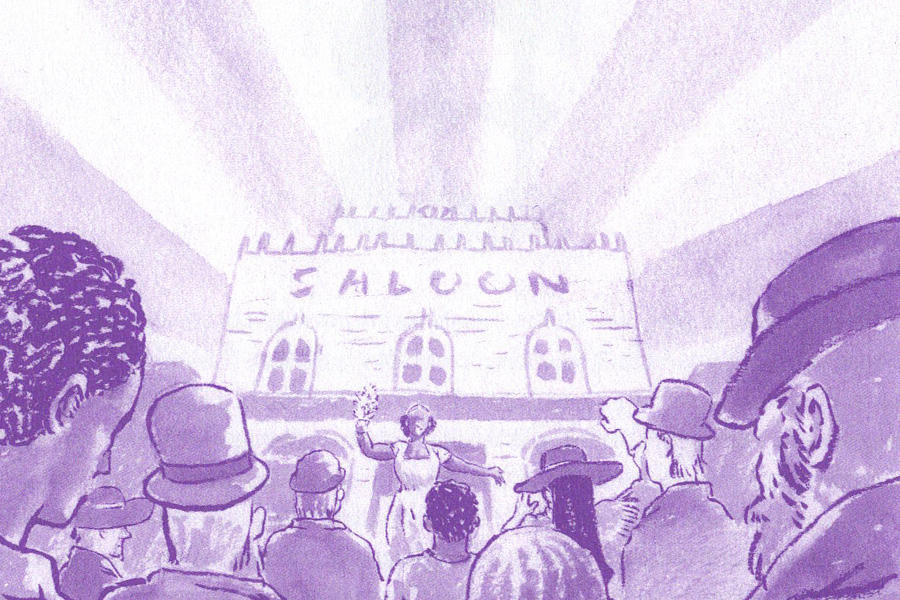

But then Butch came to town and, for no real reason anyone could tell, had stayed, spending her nights and days with Alma, who told her all about the mining company. What started as talks turned into sabotage and stolen payroll. It all escalated after Randy came to town. Butch was taking shots (literally) at company bigwigs and, given that she didn’t miss, there was a new concern: a dead boss meant no more payroll. And one sunny day a month later, a crowd had gathered in agitation, some of them mumbling Butch Dynamite’s name.

“I know y’all are wondering how we can make right by the mining company now,” Alma told the assembled town in the street outside the saloon.

Alma quieted the crowd, telling them, “The truth is I don’t know if we can make right, but I do know we’re killin’ them mountains by minin’ their guts out and someday when the veins run dry, we’ll be just a deserted old ghost town.” She let the weight of that fact sit on the crowd.

Then, she said, “Also, I know how we can save the town.”

You see, Alma’s daddy had been real insistent she learn to read because he never did, and she was as close a thing as the town had to a library. It was in a dusty old tome on botany that she’d read of an herb that could grow in rocky, arid dirt and still smelled sweeter than heaven itself.

“It’s this magical plant called lavender. It’s covered in purple flowers and has the scent of a fresh spring day,” Alma told the townfolk. “I’ve talked to the tribal folks who come through here about where we can grow it, so long as we agree to pay them tribute in perpetuity, so we’re gonna cut them in on the deal.”

Then, Alma held up an envelope and declared, “And I have here in my very own hand a letter from New York City about how much they’ll pay us to make the stuff into elixirs and soaps to clean their nasty asses!”

Butch cheered loudly. The rest of the crowd was skeptical but they had nowhere to go.

“We can make more on this than we ever did on them mines,” Alma said, assured by her own calculations and the late night talks she’d had with Butch while they held each other in the moonlight under the black willow tree on the bluff overlooking town. “Every rich lady from here to Prussia can’t get enough of the stuff, and we’re gonna be the ones to sell it to them!”

nd so it was that Sarsaparilla was organized into councils that oversaw the cultivation and distilling of lavender. The townsfolk participated in committees and subcommittees for farmers, stillers, mothers, young folks, old folks, black folks, brown folks, whores, and more. No individual working group was larger than ten people. They’d all agreed to limit sizes because the saloon only had twenty seats and it would’ve been rude to use more than half for any single meeting.

Alma coordinated all the various councils’ affairs. Butch ran security. Before long, she had organized guard duty among the former miners to keep the Pinkerton detectives the mining company had hired from messing with them. When the Pinkertons gave up, the company used its power in the statehouse down in Carson City to call up the National Guard.

But the Army captain they sent had just been passed over for a promotion, and he’d already been thinking long and hard about what it meant to be the government’s trigger finger on behalf of the fat cats tearing up the land. Alma had arranged for the townsfolk to meet the troops not with guns, but with lavender crowns and whiskey. When the captain rode up on the town, the smell from the lavender plants fermented his discontent with the government. And all of this together made a single tear drop from his eye. He’d never imagined such peaceful things nestled in among all the bloodshed.

The captain renounced his command then and there, and a fair share of deserters joined him while the rest of the soldiers went back home. Like many of the deserters, he ended up moving into town, settling down in a shack with another man who had been in the service with him. The handsome couple swore both their guns to Butch, should the need ever arise. The State Capitol’s military might was the company’s last gasp at trying to take back the town, and it had failed.

Before long, the townsfolk were shipping flowers, oils, and floral water out by the wagonful. Everyone settled into the simple, calm-smelling life they’d built together. The men who used to be miners could still afford North Carolina tobacco once in a while, but they didn’t mind the cheap stuff because they could take smoke breaks whenever they pleased, and with a little lavender bud rolled up in there it tasted sweeter than the fine stuff anyway. Meanwhile, everyone in town was allowed to take a bit of the harvest and universally agreed that their cleaning, especially their laundry, had never smelled better or been less stressful to do.

The days were hot and long, but they came with sweet nights that began with dramatic sunsets: purple skies over purple fields. It rained in spring, when it should, and the sun came hard all summer, as it should. The lavender plants grew under the town’s care, as if they, too, knew that things were good and wanted to do their best to keep it good. The sagebrush turned back to its old color, the streams seemed clearer, and Alma could swear there were more quails around again, like there had been when she was younger.

_____

Years later, alma sat with Butch one sunset under the black willow overlooking town. The miner’s daughter, now a matron in her own right, wore a yellow dress with ruffles at the neck while her paramour wore simple black denim well-worn around the edges. They were resting easy on a bench Butch had built on the spot after their knees started getting week on the climb up the hill from town.

“Do you remember the night we saw the future?” Alma asked.

“Is that a trick question?” Butch asked without looking up from the cigarette she was rolling; it was full of lavender.

“Maybe,” Alma said.

Then she continued, “But we were on this very spot many years ago, dozing in the moonlight. I said I wished all of us out here could just provide for ourselves and kick the mining company out.”

Alma looked out over the town, twice as big now and growing a family at a time as folks came round to be a part of it. She said, “You’d been kissin’ me like it was your last night on earth on account of that duel with that fool of a bounty hunter you had the next morning, but I couldn’t stop thinkin’ ’bout what I’d do if’n you got yourself killed.”

Butch gave her smoke a lick up the seam and rolled it shut. “Sorry to have foiled your plans, my dear,” she said, glancing sideways at Alma.

“Quicker with a joke than you are with that revolver,” Alma said, chuckling in spite of herself. “But that was exactly how you’ve always been, like when I told you I was worried that night and you told me, ‘If I were you, I’d be a lot more worried about what happens if I live.’”

“It made me realize I had to be worried about how I’d live after crying over your corpse in the mud. And that got me thinkin’ ’bout how the whole town would survive without a bit of muscle to hold the company off,” she continued. “I knew we needed a way to build our own world, and I spent weeks poring over my books for an answer.”

“As I recall, you left me all on my lonesome the day after I survived a duel to bury your nose in them things,” Butch said, exhaling the lavender smoke through her nose.

“And yet here I am, all these countless days later,” Alma chided. “Still sufferin’ your impertinence.”

Butch put her arm around Alma’s waist on the bench and pulled her close. Alma blushed like it was the first time she’d been embraced by this desperado of a woman.

“My point is, if it weren’t for you, I might never have taken this all on. We might never have been able to give these folks a life worth living not because a boss tells you what it’s worth by the hour, but just ’cause you can smell the lavender on the air,” Alma said. “I’m just real glad we got to do this, Butchie.”

“I love you, Alma,” Butch said.

“I love you, too,” Alma replied.

Then, Butch kissed Alma, and Alma felt so much behind it that she would’ve believed Butch had one last duel in the morning. But there was no duel tomorrow, nor were there any more bounty hunters or company men or Pinkertons ranging near town. Heck, there wasn’t even a Sarsaparilla anymore — for years, everyone had just called the town Lavender. The next one over was known as Sage, and the councils were spreading out from there.