The revival of feminism as mass movement is a key feature of the Trump era. Will it be a feminism for elites or a revolutionary feminism from below?

In April 2017 I traveled to New York to attend a weekend conference, and found myself quite happily clustering panel by panel with a group of feminists, some of whom I’d known for years, others whom I’d heard about but never met. That spring felt like a particularly confusing time to be a feminist—six months before the “Weinstein effect” took hold, when we did not yet know we were in the moment of #MeToo. Sexual abuse was not the topic of conversation that weekend, but as in many such contexts, it lingered in the air.

Instead we discussed liberal feminism’s moment. A month earlier, International Women’s Day uncovered huge repositories of conflict among contemporary feminisms, primarily between the Hillary Clinton-inflected mainstream feminism featured in the Women’s March and more anti-capitalist undercurrents. Many of us had faced intimidation from local chapters of the Women’s March as we organized in conjunction with the International Women’s Strike on March 8. In some cases, chapters called police or threatened to, aiming to remove explicitly anti-capitalist organizing from International Women’s Strike events affiliated with the Women’s March. While pink pussy hats spread across the country, a territory-war over feminism emerged.

One prominent debate was over the “women” of the Women’s March. For many conservative feminisms of the moment this “women” not only excludes trans-women, but aggressively pushes issues of race and class out of the picture. As many of us complained, this contingent of contemporary feminism seemed far too willing to embrace the apologism of #NotAllMen, protecting heterosexual culture from the thorough interrogation it clearly calls for.

This moment of liberal feminism had a few clear characteristics. Ideologically, we understood this as Lean In feminism—a vision of equality that might also be described as a feminist version of the corporate work ethic. Lean In promises a feminism of having it all: achieving self-worth through professionalization and motherhood. It’s about working twice as hard as everyone else so that you can be called a super woman. It entails not complaining, and smiling through all the indignities. Presumably, this also includes the kinds of casualized sexual harassment in workplaces everywhere that #MeToo has made public. During one of our conversations that weekend, a woman I’d long admired, with deep roots in the women’s liberation movement, spoke about such instances of harassment as hazing she’d endured in workplaces as well as political organizations throughout her life. To participate in a certain organization, she recalled, she was asked to give multiple men blowjobs.

Six months later, these kinds of stories were proliferating by the minute. Within twenty-four hours of actress Alyssa Milano’s famed tweet using the hashtag on October 15, the #MeToo hashtag had been tweeted more than half a milliontimes. Accompanying it were stories of extreme trauma, severe abuse, horrific assaults. But there were also, increasingly, stories of everyday, seemingly unnoticeable mistreatments and interactions that had, in fact, always been noticed, despite the silence.

The weeks that followed were profoundly empowering, destabilizing, illuminating, threatening. Finally, the kinds of conversations so many of us had been having for years—in small gatherings, private spaces, brief asides—were happening publicly and unapologetically. Suddenly, the kind of solidarity I’d experienced among feminists on long weekends had broadened exponentially. After a lifetime of inconsequential outrage, this sense of consequentiality was quite captivating.

To so many in those autumn months of 2017, it appeared that a feminism of some sort was on the rise. But the crises could not be forgotten for long. I came to wonder throughout those months: was #MeToo the result of Lean In, or the end of it?

The Silent Ceilings

The idea of leadership in #MeToo has been troubled at a few critical points. In December 2017, TIME Magazine named Person of the Year the “Silence Breakers,” selecting an elite group of women as movement figureheads. Along with Alyssa Milano were celebrities Ashley Judd, Rose McGowan, Taylor Swift, and Selma Blair. In addition, the Silence Breakers included State Senator Sara Gelser, Parliament member Terry Reintke, former FOX News contributors Megyn Kelly and Wendy Walsh, entrepreneur Lindsay Meyer, University of Rochester professors Celeste Kidd and Jessica Cantlon. Breaking apart this pattern of mostly white professional women were figures like Tarana Burke, an African American civil rights activist and nonprofit organizer, who began using the phrase “Me Too” for a social justice campaign against sexual abuse in 2006.

If we were to name a leader of #MeToo, it would surely be Burke. For eleven years before the celebrities started tweeting, Burke had been hard at work as a community organizer. “Initially I panicked,” she told the New York Times five days after Alyssa Milano’s tweet. “I felt a sense of dread, because something that was part of my life’s work was going to be co-opted and taken from me and used for a purpose that I hadn’t originally intended.” But this panic soon diffused, as Burke wenton to explain. She doesn’t want to own #MeToo. “It is bigger than me and bigger than Alyssa Milano. Neither one of us should be centered in this work. This is about survivors.”

“What exactly is authentic about this remarkable monster who can simultaneously speak truth and not cause pain, be honest but not inappropriate, speak up but not seek attention, communicate delicately but not seem negative?”

The possibility of a leaderless movement was certainly the inspiration for TIME’s tribute to the Silence Breakers. Yet as critics would point out, the issue was less about survivors than our cultural fascination with celebrities. #MeToo, some would claim, boiled down to our pathetic desire to feel that we have something in common with Gwyneth Paltrow or Angelina Jolie, that there is a “we” that includes both us and them.

I think that these critiques of the celebrity focus of #MeToo nearly get it, but nonetheless miss the point. It’s not that they’re entirely unwarranted. Certainly we see magazines like TIME marketizing the celebrity features of #MeToo. Yet there are other reasons why the entertainment industry has been so prominently featured in this phenomenon. First, and most importantly, entertainment has greater susceptibility to popular opinion than any other industry. In addition, film actresses and pop stars have the economic privilege not only to vocalize experiences of harassment, discrimination, and assault, but to incorporate these experiences into their branding. Even so, and just as Burke suggests, it’s about a lot more than that.

While celebrity is what many of TIME’s Silence Breakers hold in common, what binds them together is an ideology of feminist empowerment indistinct from the Lean In work ethic. Ostensibly leaderless, this vision of #MeToo captured the lurking crisis—the slow, totalizing absorption of feminism by this array of shiny, professional white women.

These were glass-ceiling breakers, ready to break their silence next. And it’s here that we start to see how #MeToo is, and has always been, two things at once: a rupture with the core tenets of Lean In, and a perpetuation of its fundamental silences. Buried in TIME’s list of celebrities, institutional elite, and corporate and political leaders are some striking exceptions, comprising most of the women of color. Sandra Pezqueda, a former dishwasher; Juana Melara, a housekeeper; and Isabel Pascual, a strawberry picker, each push us toward a different vision of #MeToo—not the spectacularized tabloid material of Weinstein’s monstrosities, but the everyday, unspeakable nightmare of sexual abuse that characterizes so many jobs in the workforce. Among the two anonymous profiles in the TIME issue were a twenty-eight-year-old hospital worker and a twenty-two-year-old former office assistant. In addition, the issue includes a brief profile of the Plaza Hotel Plaintiffs—Veronica Owusu, Gabrielle Eubank, Crystal Washington, Dana Lewis, Paige Rodriguez, Sergeline Bernadeau, and Kristina Antonova, who filed a lawsuit against Fairmont Hotels & Resorts for “normalizing and trivializing sexual assault” among employees. These stories tell us much about #MeToo as a social movement situated, for better or worse in the workplace.

Leaning into What?

The workplace has been at the foreground of feminist struggles since the 1970s, the site not only of some of the greatest achievements of the legacy of women’s liberation but also its greatest shortcomings. Along with reproductive rights, the mainstream feminist conception of equality has been measured by salaries, promotions, and employee diversity. During the 1980s and 1990s, this equal-opportunity-oriented version of feminist politics increasingly transformed feminism into a corporate work ethic: a feminism for which equality is not a given, but a hope realized by hard work.

Perhaps needless to say, such promise is entirely false. Though most jobs do entail hard work, only for a privileged few do they offer us any real fulfillment, let alone empowerment or equality. Taking apart the fantasy of a “trickle-down feminism,” Dawn Foster in Lean Out rightly observes that “corporate feminism seeks to exhibit extremely rich women, not as symbols of our increasingly unequal society and distribution of wealth, but as saviours of womanhood: because they have succeeded, now you can too.”

Appealing precisely to this trickle-down fantasy, the professional self-help book has been an inexhaustible wellspring for corporate feminist branding in the years following the 2008-09 financial crisis. Published in 2013, Facebook CEO Sheryl Sandberg’s Lean In imparts a narrative of “the will to lead,” modeling a feminism of corporate ladder-climbing and finding a “seat at the table.” For more than a year, Lean In was a New York Times best-seller, and has by now sold nearly five million copies worldwide. Co-authored by Murphy Brown writer Nell Scovell, it’s engineered to appeal to a popular readership, offering vaguely spiritual mantras for internally overcoming gender inequality in the workplace. Lean in, corporate feminism tells us: into gender discrimination or worse, into the enabling of perpetual abuse.

Without directly engaging sexual harassment in the workplace, Sandberg transmits a set of cryptic messages about “seeking and speaking your truth” on the way towards professional empowerment. On the one hand, she empathizes with her reader:

For many women, speaking honestly in a professional environment carries an additional set of fears: Fear of not being considered a team player. Fear of seeming negative or nagging. Fear that constructive criticism will come across as just plain old criticism. Fear that by speaking up, we will call attention to ourselves, which might open us up to attack.

Yet on the other hand, she imparts to her reader a set of warnings:

Communication works best when we combine appropriateness with authenticity, finding that sweet spot where opinions are not brutally honest but delicately honest. Speaking truthfully without hurting feelings comes naturally to some and is an acquired skill for others.

Throughout Lean In, the responsibility is placed on the professional woman (implicitly white) to individually surmount structural inequality, drawing from a repertoire of impossible skills. What exactly is authentic about this remarkable monster who can simultaneously speak truth and not cause pain, be honest but not inappropriate, speak up but not seek attention, communicate delicately but not seem negative? This impossible figure is crowded with parasites, eating away at her as she is asked to grapple with what Sandberg describes as “internal obstacles,” without a thought for systemic change.

While there are elements of #MeToo that are consistent with Lean In, this unruly abundance of shared experiences cannot be easily contained by the corporate feminist trap of “speaking your truth,” no matter how much it resonates. The problem with Sandberg’s idea of communication is obvious in so many of the stories of workplace discrimination that have emerged in the last year—where the responsibility to effectively communicate has been placed entirely on the worker, rather than on the abuser or the workplace itself. But leaving systemic abuse to be managed internally was never the point of #MeToo. However confused this phenomenon might appear as a social movement, there has been a persistent and unified struggle to collectively share stories and refuse the forces that silence—and this includes the corporate feminist mandate to lean in. Pushing back against this mandate, as Sara Ahmed suggests, complaint becomes a feminist practice. But this is part of the confusion: what does pushing back look like if we don’t stop leaning in?

If we are to make sense of the political possibilities of #MeToo, Ahmed’s explorations of complaint provide a helpful roadmap, filled with cautions, memories, and markers of feminist collectivity:

If you try to stop harassment you come up against what enables that harassment. The accusations that are thrown out; they might seem pointless and careless but they are pointed and careful. They are part of a system; a system works by making it costly to expose how a system works.

Providing her readers with direction, Ahmed imagines a complaint erased from memory as an unused path: “it is harder to follow, becoming faint, becoming fainter, until it disappears. You can hardly see the sign for the trees. A complaint can be covered by new growth; new policies; new statements of commitment; action plans, reports.”

More than another shattered glass ceiling of corporate feminism, #MeToo emerged as a swarm of paths and pathmaking. It is not without a history. It did not come out of nowhere. There are no leaders, no town halls, no encampments, no blockades. Rather, it is a mass mobilization of stories and storytelling, bringing political visibility to work that has always taken place in the privacy of conversations and small gatherings, hiding from public view. Feminist collectivity—while resisting the mandate to always internalize—has been forged largely in secret, as a result of these barriers.

Following the Paths

Much of #MeToo is about undoing silence, overcoming the pressure to absorb and conceal experiences of sexual abuse. While corporate feminism tells us to embrace mistreatment—even twisting it into a source of strength—#MeToo has challenged these assumptions, at times bringing visibility to the abuse that is the seamless fabric of our everyday lives.

Capitalism invisibilizes the infinite forms of exploitation that make it possible on a global scale, creating what Noel Burch and Allan Sekula have called globalization’s “forgotten spaces,” explored in their incredible 2010 documentary about the shipping industry’s control and abuse of the ocean. The agricultural fields are among these forgotten spaces. More than half of the fruit, vegetables, and nuts consumed in the US are grown in the agricultural fields of California, where workers are continually and horrifically raped, assaulted, harassed, threatened, and degraded by their supervisors. The majority of agriculture workers are undocumented, so there are no reliable statistics on sexual abuse in the industry. And what prevents so many workers from reporting rape and harassment is exactly what makes them vulnerable to the most extreme abuse.

Out of the three million migrant and seasonal farmworkers in the US, the federal government estimates that 60 percent are undocumented. Farmworker advocates, however, suggest that the number is much higher. Other unknowns include the number of young children at work in the fields, how much workers are paid, how often they are paid, and what they must endure in order to be paid. While many farms expect workers to adapt to unpredictable payment, they require them to pay for their own food, water, and often charge them daily for transportation. In a 2014 lawsuit against the farm Tapia-Ortiz, C&C, seven workers made public details of their working conditions: ten- to twelve-hour days, sometimes without pay, or pay only upon satisfaction of additional conditions; no breaks; no accessible bathrooms or shelter; extreme heat; limited access to food and water; pesticide-related health-problems.

According to the USDA, something like 70 percent of produce grown in the US is covered with dangerous pesticide residues. What are the other secret toxicities lining our strawberries and spinach?

Five years ago, stories of the “pandemic” in agriculture began to circulate. Along with several investigative pieces from popular media outlets, the 2013 documentary Rape in the Fields (PBS Frontline) brought mainstream attention to this crisis. There is little concrete data about sexual abuse in the industry, but the stories made available, obviously only one small part of the horror, are utterly devastating.

Many supervisors treat the freedom to serially abuse workers as an invisible clause in their job description. Supervisors rape women routinely, using weapons like knives or guns. This abuse includes not only habitual violent rape, but threats of withheld wages or even worse, deportation. A 28-year old worker describes being raped when her boss moved her from one part of the crop to another. Another woman recounts her boss raping her on the way to work and later harassing her at gunpoint. Children of farmworkers begin to worry about being raped from an early age. “Rape is one of my biggest fears,” says the 12-year old daughter of an Immokalee, Florida tomato-picker. “I’m haunted by the idea of it.”

The vast majority of these stories are anonymous. Together, these stories ask us to believe, without needing names. In so many of these cases, only the most horrific conditions have impelled women to come forward with testimonies. One woman is Angela Mendoza, featured in Rape in the Fields. In Mendoza’s powerful interview, she describes bringing her fifteen-year-old daughter Jacqueline to work at Evans Fruit—located in Washington’s Yakima Valley—in the summer of 2006. The foreman of the farm, Juan Marin, had a growing reputation for harassment and assault. Mendoza recalls, “He turned to my daughter, looking her up and down. ‘What a lovely daughter you have. Where have you been hiding her?’” The harassment got worse and worse, until one day, she explains, she found Marin grabbing her daughter forcefully by the shoulders. He was “grinding on her from behind, grinding his penis against my daughter!” This was the last straw, she said. “I was filled with courage.” The Mendozas filed complaints with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and quit their jobs at the farm. While the EEOC received a growing number of complaints against Evans Fruit, Jacqueline was murdered in an unrelated incident. Grieving her daughter, Angela Mendoza later found that she was dropped from the case. The story she lives to tell should haunt us. Imagine the sheer desperation she felt, bringing her daughter to work there in the first place.

Based on what we have heard from survivors, who took tremendous risks to provide testimonies, it seems clear enough that women are raped at work on a regular basis at most farms throughout the agriculture industry. It is not a matter of bad actors. These supervisors are rapists in an industry rooted in systemic violence. And just as the supervisors are not exceptional, neither is the industry. It is part of a much larger problem, with different crisis points and thresholds of intensity.

Workforce by workforce, #MeToo allows us to see this landscape of exploitation and vulnerability as a singular thing, something people everywhere face. This is in large part promising. But in imagining this systemic violence as a shared problem, it must be clear that our risks are not equal.

I worry about this embrace of our shared struggles “as women” in the moment of #MeToo for this reason, among others. The “we” conjured by today’s mainstream feminism is quite alluring—its mantras “enough!” and “time’s up” speak to collective traumas and frustrations, opening up so many possibilities. But this “we” seems to flatten these crucial differences into a white professional universality.

So far in #MeToo, workplace dynamics have been the most legible site of abuse—far more legible than the “private” acts which comprise the majority of reported and unreported cases of sexual violence. Yet the opportunity to highlight the class dynamics of sexual abuse—in so many allegations, a matter of workplace hierarchy—is continually missed with this insistence on a shared “womanhood.” We should not forget the ways in which the problem is gendered, but we also can’t lose sight of the ways in which the problem manifests in such varied forms, across so many contexts, in the vastness of capitalist exploitation. Between the Hollywood actress raped in the hotel room and the hotel worker who must clean the room afterward there are connective tissues of gendered violence. But the actress will be heard, unlike the hotel worker, because more is at stake in #MeToo than their gender.

Beyond the Workplace

Lately more jobs are looking less like jobs. This is the case throughout a number of industries, now increasingly reliant on an at-home or freelance workforce, in the new paradigm of “flexibility.” In this sense, the gig worker is a emblematic figure: supposedly self-managing and autonomous, yet living precariously, from short-term contract to short-term contract in an endless hunt for more work. For many young people today, facing a grim job market and historic rates of debt, gig work appears infinitely available through “side-hustle” apps, yet nonetheless greets them with endless risks.

“The act of telling your story is its own trauma. To survive abuse you must fight to forget, until you must fight to remember.”

Back in 2015, lots of gig workers were talking about the fate of Benjamin Golden, the Taco Bell executive who assaulted his Uber driver, Edward Caban. When a dashcam video went viral, Taco Bell fired Golden, but the real-life fears of many workers in the gig economy were hardly eased. Every day workers use apps like Uber or Lyft to find customers, often experiencing assaults in their own vehicle. Workers who use apps like DoorDash, TaskRabbit, or Handy risk much by going into the homes of customers. Stories of assault and harassment are rampant. But the boundaries are more confusing.

As “flexible” self-managers, gig workers are simultaneously their own bosses, subject to the whims of each customer. Dependent on good customer ratings, gig workers are far more likely to smile through casual acts of harassment because “the customer’s always right.” And when their work feels unsafe, gig workers are often unsure about the reporting process. Technically independent contractors, their supposed autonomy puts them in a state of constant endangerment.

The false intimacy of strangers in the so-called “sharing economy” is surely a dystopian aspect of our times, disfiguring some of the clear workplace hierarchies that, in many #MeToo allegations, illuminate the violence of power.

Perhaps nowhere are these contradictions more apparent than in the case of Uber. Since the company’s launch in 2009, drivers have experienced routine harassment and assault, while many of the media stories that initially circulated focused on the threat of predatory drivers, rather than customers. Of course, these forms of predation are by no means mutually exclusive. Structurally, however, we see a clear difference in how cases are addressed. It is extremely easy to get an Uber driver removed from the app, and over 1oo drivers have been accused of sexual assault, including incidents of kidnapping. But it is also extremely easy for drivers to be subject to such violence, and there are hardly any means for their protection. Compare this to the reaction after former Uber engineer Susan Fowler wrote a public blogpost about her experiences of sexual harassment and discrimination in the company. Immediately, CEO Travis Kalanick announced an “urgent investigation.” Since then, Fowler has been hailed as the woman who would “topple down Uber” and listed among the Silence Breakers in TIME, becoming one of the many white professionals foregrounded by the corporate feminist wing of#MeToo. While twenty Uber staff members were fired, and Kalanick took an indefinite leave of absence, the working conditions of the company’s roughly one and a half million drivers remain the same.

The complexities we encounter in the figure of the gig worker pose to us a set of problems about the contemporary workplace. Where does the workplace begin and end? When are you and aren’t you working? What does it mean when your home is your workplace? Is the Airbnb “host” who is raped by her “guest” to be blamed for “hosting” her rapist? A question like this troubles our thinking, getting us closer to the reality of sexual violence in our everyday life.

Six out of ten sexual assaults take place not in a traditional workplace but in the victim’s home or the home of a friend or relative. One in seven victims of sexual assault is under the age of six. And at least 12 percent of rape victims are afraid of reporting their rapist. A quarter of reported rapes are committed by a current or former partner. In cases of molestation, 34 percent of sexual perpetrators are family members.

The “workplace”—whatever its boundaries—is merely the anteroom of this unbounded nightmare.

Beyond #MeToo

Over the last year I’ve often thought back to those early months of 2017 spent wondering about the futures of feminism with other feminists. In our conversations we saw the crisis so vividly. Today, it would seem, the problem remains unchanged: the political monopoly of Lean In over mainstream feminism. While we might speculate that it was precisely the outrage of white professional women that brought us all the political possibilities of #MeToo, this outrage now predictably seeks to control and recuperate ‘feminism’ and give us yet another version of an ethically reformed capitalism with “woke” corporations.

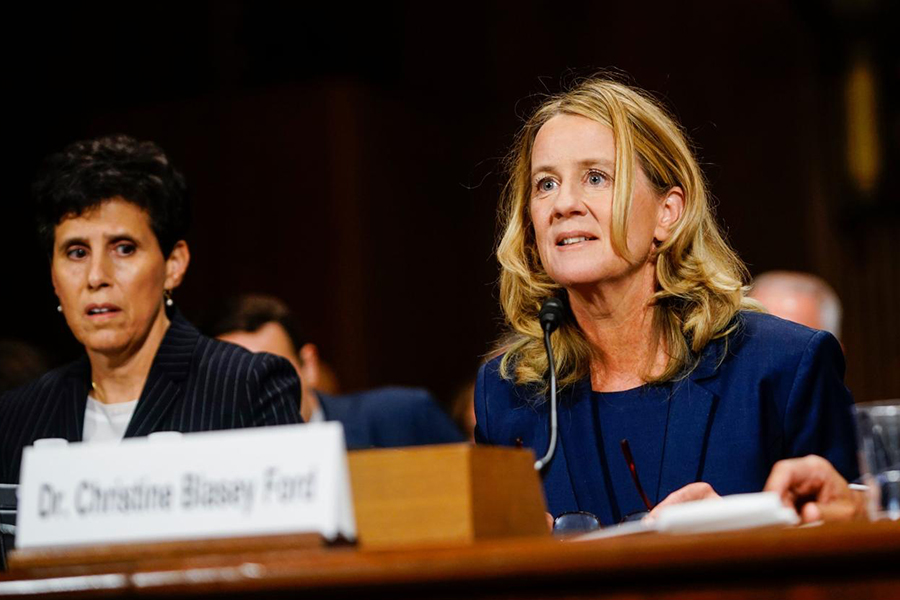

If #MeToo and the resistance to sexual abuse is to have a future, then it will have to be more than a white professional workplace struggle. But it’s hard to imagine getting out of this bind with Lean In, as we watch Dr. Christine Blasey Ford’s testimony recuperated by Republican congressmen. On September 27, so many ached as Ford—such a precise distillation of feminine empowerment and professional achievement—brought this logic to its limit, leaning into, almost self-sacrificially, the collective trauma of her testimony. Composed, highly competent, and well-armed against gaslighting in her position as a mental health specialist, Ford could not be more credible and believable in the eyes of this system. Witnessing her public discreditation should demonstrate to all of us that we won’t be believed, either—and that to keep having to prove it might not be the point anymore, if it ever was.

Like many of our stories, Ford’s has been exhaustively unheard and retold. The act of telling your story is its own trauma. To survive abuse you must fight to forget, until you must fight to remember. When you have to substantiate that you’ve been harmed, all healing you’ve achieved will be methodically held against you: whatever distance you can create from trauma provides material for speculation and endless disputes.

These disputes are happening everywhere, so that men like Kavanaugh can secure their power, while men like Trump caution us to reflect on this “scary time for young men.”

Disputes are even happening among labor organizers. A graduate student union organizer recently described to me her failed attempts to file a grievance against a professor for sexual harassment, due to pressures from other union members. Whereas fellow organizers in her union, she complained, would champ at the bit for a dozen or so hours of overtime to start up the grievance process, many were wary of pursuing a sexual harassment case, and some refused because of that particular professor’s affiliation with the members’ dissertation committees. Here and elsewhere, gender obstructs the relatively transparent labor politics of these cases, even for those best positioned (and most eager) to find opportunities to politicize the workplace.

And disputes are happening among feminists, too. I am not alone in experiencing multiple heartbreaks this year, discovering on more than a few instances that feminists who’d modeled for me a critique of sexual violence were willing to make so many exceptions to their feminist practice in order to maintain social capital and access to institutional power. I’ve discovered that the imperative to lean in, to grin and bear it, runs deep among even its harshest critics.

I keep hearing about how confusing everything is in the era of #MeToo, how messy things have become. As if it all came out of nowhere, like some kind of magic. But so much of what has been brought to the surface isn’t, in fact, so incomprehensible. So much of it is actually quite obvious: where there is power, there is abuse.

At its best, we get from this moment a map of how power works. Let’s do something with it.