Emptying the detention centers is more important now than ever.

On a late March weekend, dozens of cars approached the Hudson County Correctional Facility complex in New Jersey, which doubles as an immigrant detention center. Bumper to bumper, hazard lights flashing, the vehicles slowly circled the jail as drivers chanted from their windows and blasted their horns. This was Never Again Action’s first in-vehicle protest outside an ICE concentration camp. The spread of coronavirus has neutralized our ability to safely gather and protest shoulder to shoulder, but the need to free every person held in a detention center has never been more critical. We needed to calibrate solidarity with social distancing. So we got in our cars.

We came together out of a sense of urgency and fear: several staff members at detention centers across northern New Jersey have now been diagnosed with COVID-19; the first two ICE detainees in the nation to test positive are held in the state. The bodies of those locked inside are sites of intersection for numerous injustices at once. Held in cages by the cruel vagaries of border fascism, they are vulnerable to illness and likely will not receive adequate medical attention. Some are locked in solitary confinement twenty-four hours a day. Immigrant detainees are in the midst of an extreme crisis, and people at all four New Jersey ICE camps have gone on hunger strike to protest their cruel conditions.

Never Again Action, the Jewish-led national movement born last summer in New Jersey, is chiefly animated by a conviction that we not let the worst of history repeat itself. As a pandemic threatens the already-imperiled lives of persecuted communities, we do well to reflect on the fate met by Anne Frank. She died not in a gas chamber, but of an infectious disease contracted in a concentration camp. Ten people have already died in ICE custody this year, already outpacing 2019’s death toll. Preventable illnesses recur: complications due to septic shock, unattended heart attacks, untreated withdrawal symptoms. Here in Hudson County, Carlos Bonilla repeatedly begged for medical treatment while in ICE detention; instead of receiving proper care, he died of internal bleeding in June 2017.

Many of us have protested the cruelty of Trump’s immigration policies in the streets for years now, gathering en masse outside of detention centers and ICE offices around the country. But the COVID-19 pandemic poses new and unforeseen problems for street-based protest. As organizers, we knew that we could not allow our message to disappear from the public sphere during this moment. Too many immigrants’ lives are at risk. But New Jersey is on state-mandated lockdown, and the demands of safety and community care around infection prevention should not be flouted. So instead of using the combined strength of our bodies and voices to disrupt, we used our cars and their horns.

This reimagining of public protest builds on models of local activism that have long prioritized reaching detainees with audible messages of support and solidarity. When Brooklyn pizza-delivery worker Pablo Villavicencio was taken by ICE agents to Hudson County Correctional Facility in 2018, we swiftly organized a protest in the street outside the jail with a dual purpose: to call attention to his plight, and to offer comfort to him and others trapped inside (he was ultimately released, with enormous public attention likely playing a helpful role). At a 2019 rally in Newark for then-twenty-year-old Jose Hernandez Velasquez, who was beaten by guards and thrown into solitary confinement, a coalition led by immigrant advocacy groups Wind of the Spirit, Unidad Latina en Acción NJ, and others joined a “day-laborer band” in singing loud serenades to those inside. The history of noise demonstrations outside prisons and jails long predates our current movement, and it is within this legacy of prisoner solidarity and abolitionism that we continue to sing out to those trapped behind concrete walls.

Continued public pressure is particularly urgent in North Jersey, where all four of the state’s ICE detention centers are located. While the smallest center, in a city called Elizabeth, is run by the predatory carceral profiteer CoreCivic, all three others are located inside county jails — an arrangement created by Democratic county-level political machines eager to cash in on the detention and deportation apparatus that took shape under the Clinton administration, expanded under Obama, and exploded in the Trump years.

Agreements to cash in on ICE detention in Essex, Hudson, and Bergen counties predated Trump, but his vicious new policies coincided with bail reform in New Jersey, which took effect just as he entered office. A chance to rethink the carceral state by downsizing capacity was squandered, as newly empty beds created by inmate reductions were immediately refilled with immigrant detainees. This brought tens of millions of dollars into each county, and within a short period all three county jails became immigrant detention centers by majority.

Local activists fought this ICE complicity at every step, but liberal unwillingness to challenge the Obama administration made left-wing organizing difficult. Since Trump assumed office in 2017, though, renewed protest has rocked North Jersey. The national Never Again Action movement began in Elizabeth, and groups including North Jersey DSA, Cosecha, Resist the Deportation Machine, AFSC-Immigrant Rights Program, and SOMA Action, among others, have maintained relentless pressure on public officials such as Essex County Executive Joseph DiVincenzo, who once proudly touted the lower taxes afforded by extracting county revenue from caged bodies.

Despite this, the lure of ICE revenue has repeatedly outweighed public demands to end collaboration. For years, detainees have chronicled the abominable conditions inside New Jersey detention centers while public officials brushed them off. During October 2018 hearings in Hudson County, members of the Queer Detainee Empowerment Project described sexual abuse inside the facility and even named the official to whom they had reported it, who was in the hearing room. But Hudson freeholders renewed the contract regardless, and by every indication, have simply decided to bury the allegations. In Essex, reports from NYU Law School, Human Rights First, and other groups have documented horrendous conditions relating to food, health, and the basic dignity of detainees for years — but when activists met with county officials, they simply denied the reports. Only when the Department of Homeland Security itself issued a scathing report showing images of moldy bread, spoiled meat, and bloody chicken leaking in a refrigerator did the county move to do anything — namely, create a fangless civilian oversight body that has yet to begin operations.

As the novel coronavirus continues to deliver new threats and reorganize our priorities, carceral spaces have become especially lethal chokepoints of contagion. Forced into close proximity and unable to move freely, detainees and inmates are uniquely vulnerable to the inevitable spread’s potentially deadly consequences — a situation enabled as much by years of neglect, denial, and greed from New Jersey Democrats as by ICE’s brutality. As official responses lag, immigrants’ rights organizations around the country are struggling to deal with the new perils faced by ICE’s victims during the pandemic. As ever, a diversity of tactics is needed, from legal assistance, to petitioning political leaders, to organizing bail funds, to seeking ways to stop ICE agents attempting to carry out their vile raids. We believe that continuing to protest outside detention centers remains crucial—to reach out to those inside, and to give no respite to those who cage them.

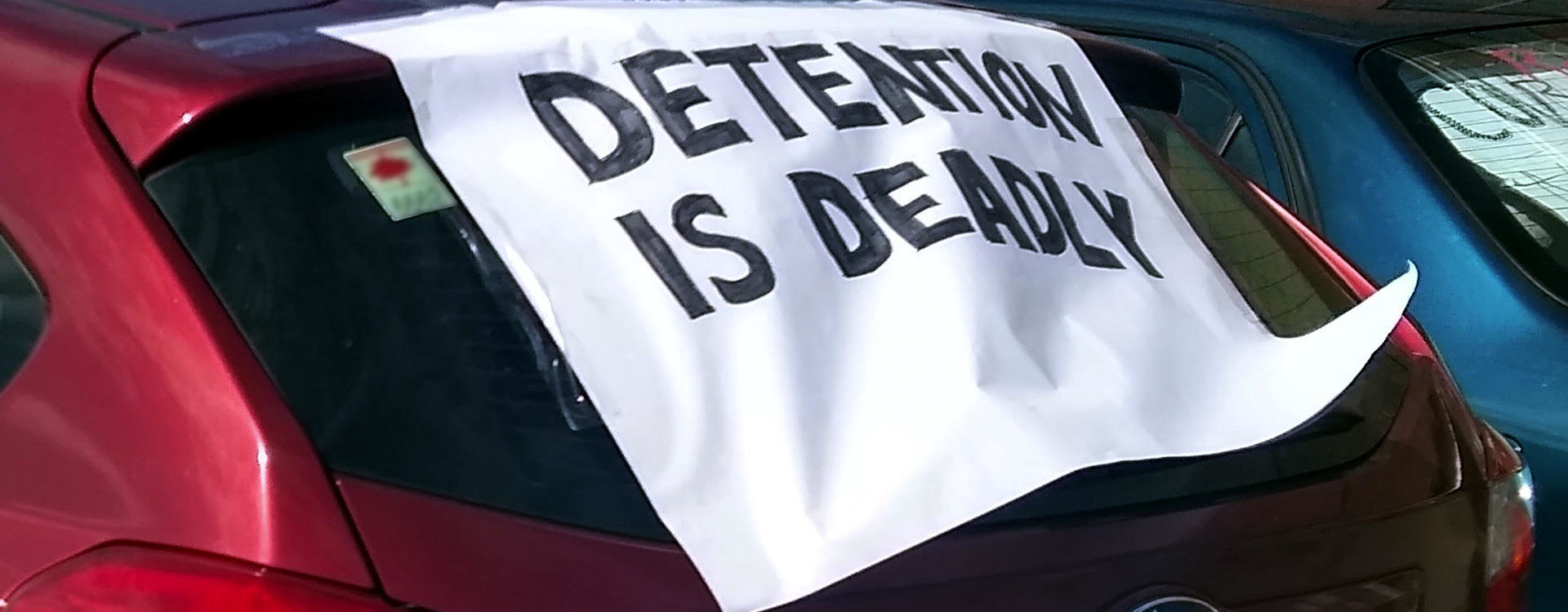

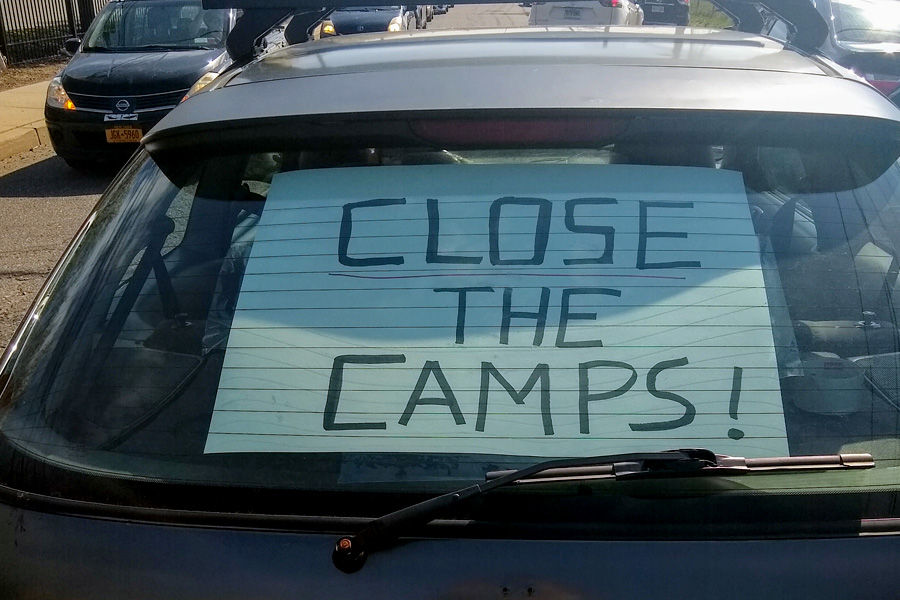

Following our first in-car demonstration, we were struck by a number of practical observations. For one thing, it was difficult to communicate, as group texts were impossible to keep up with while driving. To compensate for this, a number of leaders were appointed to guide the convoy. Comrades from places like Jersey City and New York without cars had no way to participate, since car shares aren’t an option while adhering to “social distancing” directives. We recognize, too, the grim irony in this atomized form of protest, reliant on the car, a symbol of American individualism, mobility for some, and environmental devastation — the very operations undergirding the violences that immigration detainees face. Yet there is power in the fact that we can commit to our continued struggle while keeping each other safe. Participants rose to the challenge with creative conviction, strapping megaphones to their roofs, taping signs inside their doors, and sitting on the edges of their windows to record the protest. And, since the police did not want to get within six feet of us, we were able to take disruptive actions like blocking roads without fear of legal consequence or threat of physical harm.

It is urgent that ICE detainees, as well as jail and prison inmates, be released immediately. New Jersey has already taken a leading national role in jail releases, but it is still just a start, not a conclusion. We need full decarceration and sanctuary for our immigrant neighbors. We will be back, honking and obstructing until we can block streets and doors with our bodies again, ensuring that social distancing does not halt our work but is instead merely a new and hopefully brief chapter in the work of our movement.