Treason to whiteness is loyalty to humanity.

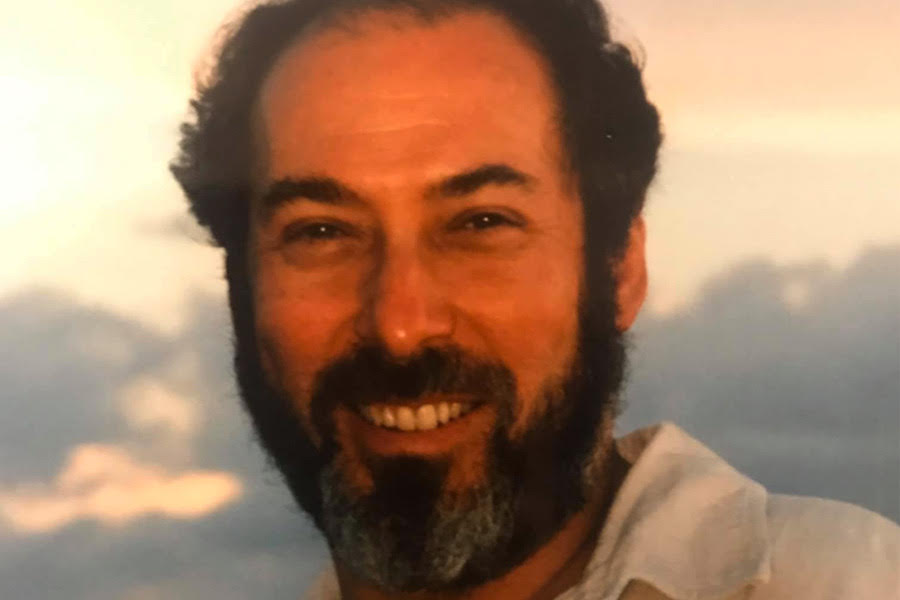

Noel Ignatiev, who died on November 9 at the age of seventy-eight, believed that emancipation from the misery and stupidity of capitalist society was not only possible but present in germinal form within the daily struggles of everyday working people. These beliefs guided his life’s work, and led him to place a particular emphasis on combating headfirst the disaster that white supremacy has visited upon all working people, including the white ones. “Labor in the white skin cannot be free,” he often quoted from Marx’s Capital, “where in the black it is branded.” In death as in life, Noel will be remembered as an autodidact steelworker, an eccentric genius, a groundbreaking theoretician, a firebrand historian, a lapidary cultural critic, an unlikely Harvard PhD, and a bitter enemy to white chauvinists everywhere, in whose scorn he basked with delight. Friends and family might remember Noel as a wisecracking Romeo, a loving father, a generous mentor, a gourmet cook, and a fierce adversary. Noel was all these things, but above all a revolutionary.

Noel became a steelworker to help instigate a revolution. He became a prominent theoretician of “whiteness” as part of a revolutionary project to abolish white supremacy and capitalism together. He studied history obsessively in order to draw from it lessons for revolutionaries. He paid scrupulous attention to the daily lives of the so-called “ordinary people” around him because he believed therein lay the key to instigating a revolution. While Noel was a dear friend of mine, I doubt I’d have heard from him quite so much if he didn’t imagine our relationship as somehow instrumentally connected to these goals. Noel died a stone-cold revolutionary. Until the very end he strove for nothing short of the abolition of capitalism through revolutionary struggle, by any means necessary. He got old, but unlike others of his generation didn’t discover with age the hidden wisdom of the progressive wing of the ruling class.

Noel was born in Philadelphia in 1940, into a working-class Communist Party family of Russian-Jewish émigrés struggling to make ends meet. He began his political life an avowed “anti-revisionist,” still believing in the revolutionary potential of the USSR and dedicated to upholding a distinctly Leninist conception of revolutionary Marxism against Nikita Kruschev’s 1956 disavowal of Stalin. Noel joined the Communist Party, USA in 1958 and gravitated toward its “ultra-left” faction, the Provisional Organizing Committee to Reconstitute the Marxist-Leninist Communist Party (POC). The POC offered for Noel the most viable option for advancing immediate revolution, grounded in the daily struggles of working people around him. Accordingly, Noel dropped out of college in 1961 to organize full time in factories, as he would continue to do for nearly twenty-five years. Cutting his teeth in hard-bitten Leninist microsects and arduous industrial labor organizing helped mold what already must have been a sharp and ferocious mind into a weapon dangerous to foe and friend alike. It also marked the beginning of a lifetime of movement experience and practical wisdom which he was always willing to share with younger comrades, even if we didn’t always want to listen.

I once confided in Noel, following my arrest at a demonstration, that I was having a hard time stomaching the wildly exaggerated sense of self-importance my comrades ascribed to our tiny group and the legal case we had stumbled into. With a smile, Noel recalled his own arrest while flyering for the POC fifty years earlier. Since joining POC, Noel had heard movement elders raving endlessly about the sophisticated police conspiracy against their tiny organization, summoning an image of impending dual power before which the state trembled. When he finally got cuffed for “disturbing the peace”—a law Noel would consistently flout for the remainder of his years—he learned the harsh truth: “They had no idea who we were,” he recalled, chuckling, “and they didn’t care.” Noel loved to recount the story of a Trotskyist he saw selling newspapers outside his factory, with the bold headline “The Working Class Demands Our Party.” Barely getting to the punchline without laughing, Noel would chortle: “And nobody was buying it!” I laughed every time, even though I’d heard the joke and lived it many times. Noel could grin, with a twinkle in his eye, at the tragicomic vainglory of revolutionary leftism, but in the next breath return to plotting our grand entry onto the stage of world history. How else can you spend a life in the movement without burning out or selling out?

Once a group of us younger comrades teased Noel about sticking with Stalinism for so long. He had been giving us shit all night, gleefully destroying some post-Marxist nonsense about “immaterial labor” by citing the first page of Capital off the top of his head, and we thought we had him at last. “Oh,” he replied, waving us off, “if you were all alive then, you would have been in the CP too, complaining about it just like we did.” When our little collective fell apart shortly thereafter, for reasons of ego and personality rather than coherent political disagreement, Noel called to cheer me up. “Say what you want about the Party,” he remarked, “but people didn’t just pack up and go home at the first disagreement like they do today.”

Noel didn’t voluntarily pack up and go home from POC. He was expelled in 1966 during one of the frenzies of self-examination such groups pass through when their relevance wanes. He soon came to count it as a blessing. “I think that the first fish that managed to crawl up onto dry land from the ocean slime,” he later wrote, “and discover a world of light and fresh breezes could not have been more shocked than I on being propelled from that cultish environment.” But Noel’s definitive break with Stalinism came not then, but when Don Hamerquist, another CP veteran, advanced a simple proposition. “Kruschev’s policies were not an abandonment of Stalin’s,” Hamerquist told him, “but a continuation of them.” In short, Stalin was not a Leninist revolutionary, but an architect of state capitalism. In telling me this, Noel was quick to clarify that Hamerquist did not in fact change Noel’s mind. His mind had already been made up, he assured me, he just hadn’t realized it. If this was ego – and I’ve surely never encountered a bigger one – it was equally rooted in Noel’s theory of how consciousness develops. “I’ve won every argument I’ve ever had,” he would often say, “but I never changed anyone’s mind.” For the revolutionary, this Wildean quip has enormous implications. Winning people over, Noel believed, is not a matter of sloganeering and evangelizing rote clichés, but of finding within people’s daily lives revolutionary premises they already agree with, but have not yet recognized as such.

The thorny and contradictory nature of working-class consciousness was a consistent preoccupation of Noel’s work, as he demonstrated an all-too-rare ability to face with sober senses the enormous evil the working class was capable of while simultaneously holding in mind its ability to save the world. In 1967, Noel and his mentor Theodore Allen co-authored the germinal essay “The White Blindspot.” At the time, major left organizations advanced a line characterized by the slogan, “black and white, unite and fight,” meaning that differences should be set aside in the name of some abstract common struggle. Pointing to the structural white supremacy baked into the workplace by hundreds of years of US history, Noel and Allen argued that any struggle that did not address white supremacy head-on, lining up behind the demands of the workers on the lowest racialized tier, was bound to reinforce the racial division of labor, to the ruin of any strategic program for actual unity. Drawing from W.E.B. DuBois’s classic Black Reconstruction in America— a book Noel told me “every American radical ought to have their face rubbed in”—the duo formulated the concept of “white-skin privilege” to indicate the perks offered to white workers by the US ruling class, in exchange for which the former foreswear all meaningful solidarity with their non-white coworkers, and bind themselves instead in a self-defeating alliance with the white ruling class. The task of the revolutionary, they argued, is to break this alliance.

Older and more experienced than the average student activist of the late 1960s, Noel became an important member of the New Left, serving as a national officer in Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) in 1969. He subsequently emerged as a powerful voice amid its dissolution, first within the Revolutionary Youth Movement (RYM), and then as one of the leaders of the Revolutionary Youth Movement II (RYM II), a split from the faction of RYM that became the Weathermen. Noel penned a legendary polemic against the nascent Weathermen, entitled “Without a Science of Navigation We Cannot Sail in Stormy Seas,” which addresses with remarkable lucidity questions that continue to plague the left and in places reads as if it were written last week.

“Politics,” Noel would often say, “is not arguing with people you disagree with, but finding people you agree with, getting together, and doing things.”

Beyond the polemic at which he exceled, Noel’s adult life was defined by practical work at the point of production. In late 1969 Noel, Hamerquist, and a small group of former RYM II cadre and other Chicago-area radicals formed the Sojourner Truth Organization (STO), a group dedicated in its early years to revolutionary factory organizing. STO drew upon and developed the theses offered in “The White Blindspot,” alongside the organizational theory of Antonio Gramsci, the praxis of C.L.R. James’s Johnson-Forest Tendency (JFT), and the radical organizational experiments of Detroit’s League of Revolutionary Black Workers (LRBW). Following these influences, STO developed novel forms of independent shop-floor organizing while actively contesting the white supremacy intrinsic to factories, trade unions, and the broader capitalist society.

Honoring the true spirit of Lenin, STO based their practice not on inherited scripture and rehashed platitudes from different times and places, but concrete engagement with the particular circumstances in which they lived. And like the League, STO thus dispensed with any lingering romantic notions about labor unions as revolutionary instruments:

Unions are a necessary development out of workers’ spontaneous struggles against their oppression. While many of those who fought and died to build unions were moved by far loftier aspirations . . . unions have emerged as institutions which channel workers’ discontent into paths which are compatible with bourgeois rule. Most important of these is the widely recognized complicity of US unions in maintaining and promoting national and sexual divisions in the working class.

Just as the League had to work outside union officialdom to contest white supremacy and advance a revolutionary strategy, so too did STO push for independent and experimental worker-led initiatives outside the structures of union officialdom, as part of a coherent revolutionary strategy. My favorite offering from STO’s numerous workplace publications, which to be clear were largely serious affairs, was the candidacy of “Filthy Billy,” a trashcan, for shop steward. He was, his campaign literature declared, “the can-do can-didate.” Similarly, Noel told me he was always opposed to automatic dues checkoffs, a sacred cow of reformist unionism to this day. “I just liked to see my union rep every now and then,” he told me, chuckling at the fact that union officials had to come to seek him out to collect.

This spirit of playful subversion accented a serious commitment to workplace militancy that declined prefigurative “movement-building” in favor of a militant minoritarian praxis, inspired by the nineteenth-century abolitionist movement against slavery. Noel tirelessly argued that the abolitionists presented a better model for revolution in the United States than the revolutions in Russia or anywhere else. In a recent and indispensable reflection on revolutionary strategy, Noel called their approach “creative provocation.” According to this strategy, the biggest problem facing a small group is not how to attract the masses into its ranks, but how to best make its modest forces reverberate throughout society with maximum impact. “Politics,” Noel would often say, “is not arguing with people you disagree with, but finding people you agree with, getting together, and doing things.” Political action is therefore not a matter of convincing people of your point of view, but orchestrating the circumstances under which they can take action together. It’s no coincidence that Noel lived his life in emulation of John Brown, who he claimed was perhaps the only white person to ever completely transcend whiteness.

Noel hung on to the industrial strategy until 1984, shouting the words of James and Marx over the clanging and whirring of the machines on the slowly depopulating shop floor. Thankfully, by his own telling, at least one factory where Noel worked for some years, US Steel, never got an honest day’s work out of him. Instead he roamed from station to station, toolkit in hand, agitating and listening, with careful attention, to the revolutionary potential of even the most banal workaday gripe. By the time he was receiving vile threats on the internet, he told me, he’d become used to it from decades of reading cowardly invectives anonymously scrawled on the men’s room walls of the factories where he daily defied the color line. I also knew he got a kick out of it. Noel believed that a white person can judge their antiracist praxis not by how many nonwhite friends they have but by how many enemies they’d made of white racists.

In the mid-eighties, when factory employment became untenable and STO was on the wane, Noel charmed his way into a Harvard graduate program, despite never having completed his bachelor’s degree. When a nasty back injury ended my own (thankfully shorter) blue-collar career and I entered a doctoral program, I asked Noel if he had any trouble making this transition himself. “It was the easiest thing I ever did in my life!” he boomed, offended by the question. “The professors were afraid of me!” I didn’t doubt it. He recalled sitting in a smooth leather chair in a cozy student lounge, listening to jazz performed live by his classmates, and thinking to himself there was absolutely no way he’d ever go back. “If the guys back in Gary, Indiana knew how good I have it here,” he recalled musing, “the entire steel industry would come to a halt!”

Though the early days of STO were the period Noel considered his most effective political work, he is best known, loved, and reviled for his writing and editing of the journal Race Traitor. Below a banner proclaiming “treason to whiteness is loyalty to humanity,” Noel and STO fellow-traveler John Garvey produced sixteen volumes of provocative theory and analysis geared toward the practical abolition of “whiteness,” therein theorized as a social pact foreclosing solidarity based on common humanity. Noel contemporaneously released the classic historical study, How the Irish Became White, popularizing for a wide audience the history and theory which he and Allen had espoused for decades. Noel’s work from this era, and its significant cultural reverberations, influenced an entire generation of activists and thinkers, popularizing the then-fringe notion that race was a “social construct” determined by a confluence of political and economic forces. It also led to an unfortunate trend within so-called “white studies,” of clinging to whiteness and white identity rather than taking it apart in practice. The point of studying whiteness, Noel never tired of pointing out, was to abolish it. Needless to say, an entire academic field reifying “whiteness” drove Noel as nuts as the “privilege checking” industrial complex which owed some of its origins to “The White Blindspot.” Noel fought both opportunistic trends tooth and nail in the pages of Race Traitor

Throughout his years working on the magazine, Noel remained very active in revolutionary organizing, offering sage advice to younger organizers, and making himself available for whatever the struggle demanded of him. His final project was Hard Crackers: Chronicles of Everyday Life, a journal we conceived and edited together along with a motley, multigenerational crew of revolutionaries Noel had assembled over fifty years of class struggle. By focusing on stories that capture contradictions at the core of American life, Hard Crackers demonstrated the commitment to the revolutionary potential of everyday working class life that had oriented Noel since the beginning. “American society is a ticking time bomb,” an editorial statement declared with Noel’s characteristic flair, “and attentiveness to daily lives is absolutely essential for those who would like to imagine how to act purposefully to change the world.”

In his political and personal lives, which often overlapped, Noel possessed an irresistible charisma. Like a lunar body that alternatively pulls or repels others into its orbit with a great force but with ultimate indifference to the collisions and chaos it catalyzes, Noel’s strengths were also his weaknesses. The indefatigable adherence to clarity of principles which propelled his projects for decades simultaneously became the source of a kind petulance, or badgering, or sometimes, bullying. Noel’s thirst for conflict could not be slaked; if he finally won you over or just wore you down, he’d change his position just to keep the fight going. For a long time I told myself that this was probably what it was like to hang out with Lenin, and just tried to just roll with it. Recently, however, I had to tell Noel, to his great disappointment, that unlike him I actually did not enjoy arguing. He complied with a grumble, but not before trying to pick a fight about it!

While this foible surely helped him through decades of hardscrabble sectarian dogfighting, dangerous political work in factories, and the death threats at which he laughed until his final days, it was of less help when running our blog. And it became more serious when it coupled with his isolation from the movement activity that nourished his best work, and led to a contrarian spirit which sometimes verged on outright trolling. While I will forever cherish the honor of working with Noel on Hard Crackers, and seeing my name alongside his on the masthead of a publication, I must confess that every time a new post went up on the blog, my stomach sank. While Noel likely had more faith in “ordinary people” than I did, believing as he did that they have no need whatsoever for seemingly any of the left organizations existing in our moment, I nonetheless retain practical and personal affinity with much of the actually-existing left, to whom Noel delighted in offering one big, flaming middle finger after another. This tendency was particularly noxious on Facebook, where rhetoric becomes inflated in inverse proportion to substance and political stakes. The several times I broached the issue with him, suggesting that his time could be better spent writing about the US Civil War, or attending to his memoirs, or doing fucking anything besides taking all comers all day long online, I felt a bit like Engels must have trying to convince Marx to set aside his own outraged essays about this or that benighted contemporary and finish his goddamned books already.

A mutual friend put it best: “Noel was an institution, and what institution aren’t we critical of?” The older I get the more I appreciate how these big personalities and monumental egos that every leftist loves to hate and hates to love are an essential part of political organizing, no matter how much we wish they weren’t. Through charisma, coercion, or the amazing power of sheer bullshit, they hold combustible compounds together for as long as possible before the whole thing blows sky high. All the while they provide consistency, clarity, and focus. They anchor projects for years as countless others come and go with the passing wind. They challenge us to be stronger, and wiser, and better, and if we fail, they are strong and better and wiser for us. And when the going gets tough, they are the first ones to get punched in the face, figuratively and sometimes literally, and it helps that many, like Noel, seem to enjoy it. Usually we have to kill them in the end, and something tells me Noel would have been fine with that too, if the ravages of time hadn’t done the job first.

Noel’s legacy is impossible to capture in one place, and I’m grateful that both his friends and enemies are weighing in to provide a robust picture of the enduring impact he has made on the world. I only wish to add that at a moment when both the far-right and many on the left are hard at work fortifying and defending the walls between the so-called races, whether under the guise of “culture,” “experience,” or “biology,” the approach Noel advanced in word and deed throughout his entire life furnishes us the tools to take race seriously while also taking it apart. While Noel’s death leaves a terrible void in my life and the lives of countless others, perhaps there is a silver lining: Noel is now being talked about more than he has been in decades, at the moment when a Race Traitor revival stands long overdue, striking as it does an arduous path between the Scylla of race blindness and the Charybdis of race fetishism.

A few years back, on a long drive from Western Massachusetts to Brooklyn, I asked Noel a question that sometimes keeps me up at night, as civil society across the globe unravels at a pace matched only by the degeneration of the the very ecosystem upon which human life depends, and as the messiah of working-class revolution patiently idles in the wings of the world stage.

“What if there’s nothing underneath it?” I asked.

“What do you mean,” he replied.

“What if there’s no future society underneath ours?”

He paused, as if he’d never given the question any thought.

“Well,” he said at last, with a twinkle in his eye, “I guess we’d be in real trouble!”

We laughed heartily.

Further Reading

Noel Ignatin and Ted Allen, “The White Blindspot“

Noel Ignatin, “Without a Science of Navigation We Cannot Sail the Stormy Seas”

Noel Ignatiev, “Creative Provocation: Strategy for Revolution”

Michael Staudenmaier, Truth and Revolution: A History of the Sojourner Truth Organization, 1969-1986