For all its guilty memorials, Germany has never fully acknowledged its African genocide.

Bones aren’t always political. For vertebrate animals they lie unseen, supporting the muscle, holding the cartilage, and serving as a vessel for marrow. Bones also supply us with metaphors: “in one’s bones” alludes to one’s innermost feelings, while “to the bone” evokes a deep wound. Under the right conditions, some bones can even become fossils.

The Museum of Natural History in Berlin, Germany celebrates bones. Upon entering the museum one is presented with a spry graveyard of fossils, an obeisance for German scientific expeditions. Towering over thirteen meters high, the reconstructed bones of the Brachiosaurus brancai stand erect at the museum’s foyer, while piles of fossils cower in the shadows — fragments of the past revived by the rapt gaze of young visitors. Formerly known as the Brontosaurus, the Brachiosaurus brancai is an ossified Jurassic treasure. Between these walls, one can view an array of dinosaurs, the skeletons of birds of prey, the magnificent worlds of bees and wasps. Whether the collections are preserved in formaldehyde or the aftermath of fleshless remains, children are invited to imagine elegiac giants and Lilliputian insects meandering in emerald coppices.

Yet in reality, the museum is the resting place — though hopefully not the final one — for many African artifacts and remains. The Brachiosaurus brancai, as well as the Kentrosaurus aethiopicus (stegosaurus), Pterodactylus (pterodactyl), and certain fossilized corals and plants, were collected in Tanzania between 1909 and 1913. Reading the museum plaques, a careful observer will note brief references to the Tendaguru expedition, which led to the transfer of 225 tons of prehistoric fossils from Tanzania to Berlin — one consequence of German colonialism.

At the Medical History Museum at the Charité Hospital in Berlin, the bones are not as visible as they once were. In previous years, the skulls of the Herero and Nama people of present-day Namibia were catalogued and publicly displayed like the fragments of dinosaurs and primeval birds.

Germany is still grappling with the legacy of colonial violence in its former African colonies, recognizing the question of historical amends raised by this past. From 1884 to 1919, with the aid of administrators and scientists, the German Empire collected human skulls and primordial fossils from Deutsch-Südwestafrika (present-day Namibia) and Deutsch-Ostafrika (Burundi, Rwanda, and Tanzania). The skulls of Nama and Herero people were brought to Berlin and eventually housed at Charité. For the German scientists who appropriated them, these bones were enlisted to support their racist claims, a way of furnishing corporeal measurements to “objectively” verify their notions of white supremacy.

These bones lie at the very heart of debates about German colonial history. Namibian and Tanzanian activists like Mnyaka Sururu Mboro, the co-founder of Berlin Postkolonial, have argued vehemently for the repatriation of these remains and for the involvement of African communities in tracing the histories of these remains back to their origins.

_____

Museums are sites of contradictions, telling ambiguous tales about the origins and trajectories of their objects. Museum signage does not tell visitors how displays were acquired, whether collectors paid for objects, what purpose these objects served, and how their meaning continues to evolve.

Namibia and Tanzania were a living laboratory for the Imperial German Army, allowing for experiments with strategies of pacification and elimination that the Nazis would inherit. Here scientific language served as an apologia for genocide, as colonizers observed and experimented on African prisoners and the deceased. In their photo essay, “Visual Archive of Colonialism: Germany and Namibia,” George Steinmetz and Julia Hell describe the occluded aspects of Germany’s colonial history, a history often unexamined by German laypeople. When Germans began to collect African objects, the human remains and premodern fossils were originally fragmented, scattered. Now they are part of a growing constellation of museum curation. These materials were not transplanted to Berlin by chance, nor did Africans willingly give them away. Mass death, colonialism, and white supremacy made this displacement possible.

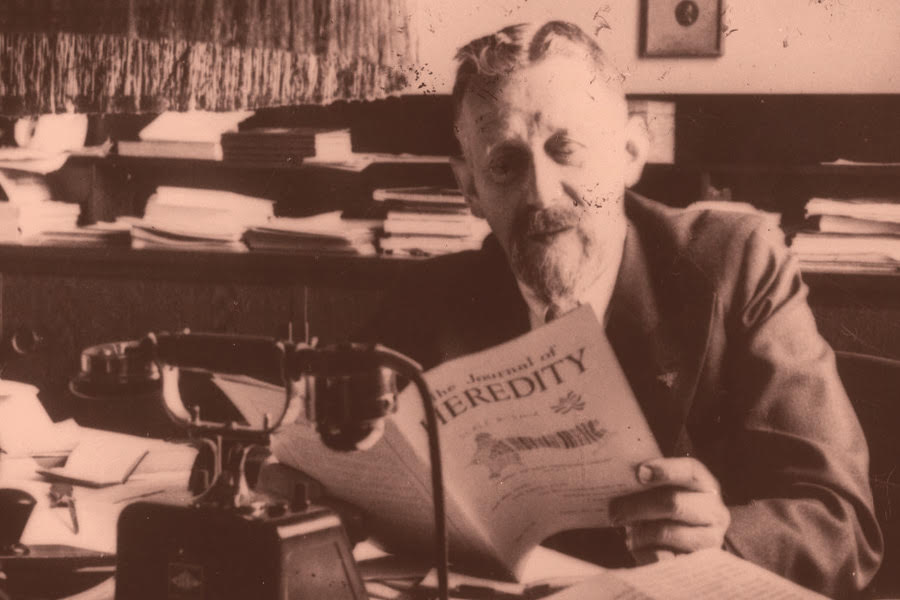

German scientists were agents of racial “science” directly linked to experimentation on African bodies in the early twentieth century. Eugen Fischer, the director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Anthropology, was involved in the campaign to measure and catalogue the skulls and physical features of African prisoners in Southwest Africa, which he hoped would prove the superiority of the Aryan race. He later served as a “racial hygienist” in the Third Reich. The zoologist Leopard Schultze worked with dead bodies, acquiring approximately three hundred skulls of deceased African prisoners from Namibia’s concentration camps. These two men were part of a network of scientists, officials, and administrators who later promoted the racist ideology of the Nazi regime.

Though the German government has yet to acknowledge these actions as genocide, the Imperial German Army committed massacres in their Southwest African and East African colonies during the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. Despite uprisings by the Herero, Nama, Maji Maji, and countless other groups, living humans, minerals, and bones were transplanted to Europe, making them inaccessible to most Namibians and Tanzanians.

German colonialism in Africa is underestimated at best, or, at worst, entirely unknown. The process of partitioning the African continent into European colonies and protectorates would come to be known as the “Scramble for Africa.” “Scramble” is a deceptive term, however, suggesting that the results were haphazardly produced, like the Lego structure of a five-year-old. In reality, the plan was judiciously executed by thirteen European powers in 1884 in the city of Berlin. Carving a vast continent into pieces, these European governments deftly exercised varying forms of violence on Africans, their blades already sharpened by prior European “civilizing” and military commissions.

From the late-nineteenth to the early-twentieth century, the Herero, the Nama, the Maji, and many other peoples excluded from German history textbooks were subjects of the German Empire. They were annexed to a European nation-state that transferred materials and goods, extracted gold and diamonds, and made alliances with the sovereign indigenous leaders. Apologists of German imperialism will say that this period was short-lived and less horrific than the plights of the British, French, or Spanish territories. Yet other voices understanding the core dimensions of imperialism would directly engage with Germany’s colonial aftermath and pave the way — as Hannah Arendt eloquently does in The Origins of Totalitarianism — towards connecting German colonialism with its fascist history.

German colonialism in Southwest and East Africa — as played out in Namibia and Tanzania — involved mineral extraction by imperialists, political resistance by African inhabitants, and the persecution of African dissidents by German administrators. While bones were shuffled and blood spilled, mineral resources were central to the colonial project. Like other European colonial powers in Africa, Germans acquired diamonds, gold, and platinum. This was made possible by a cast of characters who migrated from one colonial context to the next, often relying on enterprise and adventurism to enact their manifest destiny. For colonial Namibia, it was Adolf Lüderitz who laid the groundwork for German settlement, while for colonial Tanzania, Carl Peters advanced the German imperial charter.

Repatriation is central to undoing the damage of the past.”

Prior to official German colonial rule, Lüderitz, a German merchant, sought to protect German financial and political interests in Nama and Herero lands by investing in the right to mine for gold and diamonds. By acquiring approximately one-third of Namibian land — which would later become Deutsch-Südwestafrika — he would solidify European satellite rule. With £770 in gold coin and 260 rifles, Lüderitz, and eventually Germany, claimed jurisdiction over this land. The extent to which he paid for Nama and Herero land is contested, but we at least know he underpaid for territory worth far more in the European mercantile system.

German colonialists often laud Lüderitz for convincing the state to establish settlements and pursue gold mining. He did not live to see his colonial imagination fully realized, however. During an expedition in October 1886, he, his fellow settlers, and his boat, disappeared on the Orange River in Southern Namibia. Lüderitz did not materially profit from the land that he purchased, but the German state did when it eventually mined gold and diamonds in the colony. Twenty years after Lüderitz’s death, the Berlin-based German Colonial Society for Southwest Africa profited from the diamond mines Lüderitz was himself unable to find.

While different in size, scope, and strategy, Deutsch-Ostafrika involved similar ambitions for exploration and resource extraction. These began with the aspirations of one man. The Society for German Colonization endowed colonial administrator Carl Peters with the power to promote the interests of the German East Africa Company in Tanzania. As an explorer and Imperial High Commissioner, his brutality towards the local population included sexual crimes against indigenous women. A 1896 New York Times article describes an international scandal in the German Reichstag: the socialist August Bebel and many others accused Carl Peters of barbary for murdering Black people in colonial Tanzania. Over time, he was discredited by his colleagues, dying in the administrative ranks of Germany. However, his methods were celebrated two decades later by a rising star of fascism: Adolf Hitler.

By the late-nineteenth century, Namibians and Tanzanians were in open rebellion. In Namibia, the Khaua-Mbandjeru rebellion of 1896 was one of the first of a wave of coordinated resistance movements by the indigenous population of the region. In Tanzania, Abushiri ibn Salim al-Harthi and his comrades initiated the Abushiri revolt of 1888. The Arab and Black militia employed a range of tactics, from political negotiation to guerilla fighting. None of these methods aligned with the German Empire’s desire for absolute rule. Unsurprisingly, the Germans executed Abushiri by public hanging. Even more gravely, the militia’s defeat ensured that Tanganyika land would go through multiple transfers — from the hands of the indigenous population to the German East Africa Company, and eventually to the German imperial state.

The genocide of African people was at the heart of the German colonial project and the murderous policies of the Nazi regime. Before the Nazis constructed concentration camps that murdered European Jews, Romani, Black Germans, disabled people, sexual minorities, and communists, they built concentration camps in the rolling hills of Namibia for the Nama people. During the Maji Maji rebellion in Tanzania, German colonial administrators starved out up to three hundred thousand people. Between 1904 and 1908, one hundred thousand Nama and Herero people were murdered during the German Imperial Army’s campaign.

From the Caribbean and Latin America to Asia and Africa, people carry the colonial past in their bones. Namibia and Tanzania are no exception. Nevertheless, the global fight being waged now for reparations is deepening our sense of history and outlining a pathway to long-overdue amends.

_____

The debate on reparations is multifaceted, especially as its pendulum swings between the political and economic dimensions of the relationship between the formerly colonized and their former rulers. Amongst the African diaspora in North America, Latin America, and the Caribbean, there are millions of direct descendants of slaves, indigenous people, and Europeans. The 2020 US presidential elections have also re-enlivened the debate on reparations. Given the scale of historical tragedies, some argue that reparations must be global. Repatriation must be integral to reparations, especially in cases outside the transatlantic slave trade and African diaspora.

Early in the twentieth century, Marcus Garvey catalyzed a pan-American international debate on reparations and the term has long been used by Black nationalists and residents of former slave colonies in the Caribbean, Central America, and South America, as well as sub–Saharan African nation states. Reparation supporters have appealed to the League of Nations, the United Nations, the US Congress, the EU, and the British Parliament. The former president of Zaire (present-day Democratic Republic of Congo), Mobutu Sese Seko demanded the restitution of African arts before the UN General Assembly in 1973. Seko convinced the African Museum of Art in Belgium to return 144 artifacts. The Edo State government and the Benin royal court are demanding the creation of a museum in Benin for materials that were stolen during the British expedition of 1897. As Godwin Obaseki, executive governor of Edo State, puts it, “These works are our ambassadors. They represent who we are.”

Mass death is deemed “genocide” only when the victims are recognized as human. Beyond public recognition of this simple fact, how should perpetrators make amends? What happens when scientists are complicit in murder? Nearly eighty years after the first punches were thrown, the 1985 UN Whitaker Report on Genocide listed the German massacre of the Hereros as genocide alongside other twentieth-century massacres, from the 1915 Armenian genocide to the 1919 Ukranian pogrom against Jews. The German government, however, only acknowledged the Imperial Army’s massacre of the Nama & Herero people as genocide in 2015; they had previously classified the event as an atrocity. As Joshua Kwesi Aikins, an academic and political activist in the Afro-German movement, told me in an interview: “It is up to this generation to demand that Germany recognize violence.” There are reasons for Germany’s initial amnesia about these crimes, however: admission would warrant compensation.

Apologies for colonial violence are the first step, but they must extend into material, ongoing action. In Germany and beyond, the legacy of colonialism lives on in the names of streets and institutions. Renaming is one way to strike at the roots of this violent past. Activists with the Initiative of Black People in Germany have requested the renaming of streets in the African quarter: Adolf Lüderitz, Gustav Nachtigal, and Carl Peters. As I walked through Wedding, a working-class multiethnic neighborhood in northwestern Berlin, the tour guide reminded us that rather than erase history, residents want new street names that honor those whose lives were lost in German colonial rule: Maji Maji Boulevard, Anna Mungunda Boulevard, Cornelius Frederiks Street, and Bell Square.

The reparations project leads us back to the bones. At what point do we start to question what is on display, who is able to see it, how the gaze produces power? In the United States, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, in effect since 1990, aims to return cultural objects and remains to their original Native American homes. Thousands of miles away, Australian museums holding Aborigines’ human remains have begun repatriating materials to the descendants of the colonized. Across the world, the effects of colonial science are undeniable, but often they remain invisible: many Germans have gone their entire lives without knowing which objects were taken from Namibia and Tanzania. Scientists and museums must face their past. The Tendaguru expedition was not an innocent exploration — it was an act of violence.

The plight of remains has also been central to the reparation and restitution debate for Africans living on the continent. While the German government has returned two dozen skulls, they may have thousands more. The initiative to return the skulls originated with the Herero and Nama people themselves, who wanted control over their collective memory. When pressed by descendants in the Nama Traditional Leaders Association, the Stuttgart Museum in Germany returned a bible and whip that once belonged to Chief Hendrik Witbooi — a nineteenth-century anticolonial leader in Namibia. Herero and Nama representatives have also sued the German government. The scale of materials that were collected and the terms of settlement suggest, however, that the negotiations are an uneven affair.

The key question is how to disrupt the uncomfortable, uneven relationship between former colonial powers and their former subjects. Countries like Germany possess the memories, profits, and materials of former colonies but present them only with patronizing relationships and perfunctory international aid programs. Reparations is colonial accountability with teeth. We should reckon not only with economic recompense, but with lost materials and silenced stories. Taking control of the narrative could be one path towards the liberation of the oppressed.

Reparation can upend historical wrongs. When it works effectively, it acknowledges the humanity of the oppressed, allowing people to meet their economic and psychological needs. This means the ability to pay off inordinate debt fueled by lifetime bondage to colonial crimes, but it also means returning artifacts that have been stolen. Repatriation is central to undoing the damage of the past.

But there might be other avenues toward restitution, ones that more directly empower the formerly colonized. Several years before contributing to a report that calls for the restitution of African objects, Felwine Sarr argued in his book Afrotopia:

Africa has no one to catch up with. She must no longer run on the paths indicated to her, but walk briskly on the path she has chosen. Her status as the eldest daughter of humanity requires her to step out of the competition, this infantile age where nations are watching each other to know who has accumulated the most wealth, this frantic and irresponsible race that endangers the social and natural conditions of life.

For Sarr and others, reparations would mean a radical reimagining of the African continent. Reparations would allow the dispossessed and the displaced to make demands on their own terms, through collective action, beyond the nation-state and its control over cultural legacy and collective memory. Reparations will not take place in the museum corridors of Berlin’s Natural History Museum or the display case at the Medical History Museum alone. Only in a future beyond empire and capital can we properly lay our ancestral bones to rest.