Hip-hop on horseback, against Billboard apartheid

Country and hip-hop are the last two indigenously American genres standing. No cultural tradition is purely indigenous, and elements of each can be traced back to Africa, to Scotland, to the Caribbean, and so on, but the claim is clear enough. The syntheses happened in the United States, and both genres in different ways signify “America.” Not only do they retain their vitality, they have for some time existed in parallel, best enemies buoyed and constrained by authenticity, selling in similar volume and, most importantly, retaining the kind of committed audiences that have allowed them to weather the digital storms and market restructurings—not unaffected, not unchanged, but more or less intact.

This is already to assume that we know what genres are, about which I am still unsure. They are fucked in general, and especially in the realm of music, where matters are especially confused by the regular treatment of “pop” as genre rather than marker of popularity, a category self-evidently able to include any genre if it sells enough. As long as someone out there is willing to say “that song is more pop than rock” and someone else is willing to pretend those syllables have any meaning, it will be difficult to reach any clarity.

This confusion about pop is possible in the first place because genres are already at once musicological, ideological, and market categories. The idea that sounds make genres and the idea that genres have worldviews are not mutually exclusive, and much of the non-conscious work of genre goes to aligning these two ideas until they seem like one, allowing the resulting products to seek their proper markets in a way that seems natural. There can and indeed finally must be some variations, some seeming challenges to the format, that both demonstrate supposed aesthetic autonomy and allow for genres not to change, exactly, but to modulate themselves in accord with modulations of the world in which they have meaning, all the while not being so innovative as to lose their claims on the audience and its sense of authenticity, which is to say, its ideological presuppositions.

The ideological presuppositions of hip-hop and country are, as with all mature genres, too elaborate to detail in less than a book or maybe a library. But the most basic of them are clear and crude: the sibling genres are dramatically raced, black and white. This is not to say that all artists obey the racial distribution, much less all fans. Nonetheless, racial ideology sets the basic terms for authenticity in each genre, and thus the convention through which songs can seek markets through airplay, streaming categorizations, music store placement, review venues, and so on.

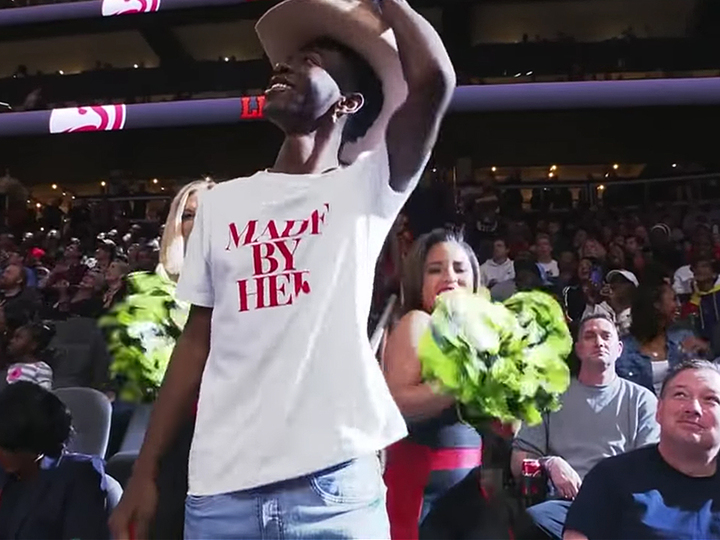

This is the longstanding genre dynamic into which “Old Town Road” enters. Confabulated from easily available samples and a charismatic vocal in the I’m-only-sort-of-singing style that bridges Soundcloud rap with Drake, the product of a Tweetdecker/semiprofessional troll using for the moment the name Lil Nas X, it has caused a sensation by going viral online, which now—unlike a decade ago— means that it can be measured for the authoritative Billboard charts. But which charts? That is the question.

Lil Nas X, born Montero Lamar Hill, has described the song as “country trap” and that appellation (or “trap country”) has mostly stuck for adequately online music types. It supposedly has a trap beat if you believe there is such a thing (there isn’t, there are just beats that trap songs use). It also has a banjo, which we could pretend is country but, you know, isn’t; you can tell because the sampled banjo comes from a Nine Inch Nails song no one has ever supposed to be anything but alternative rock whatever the fuck that is.

In any case, “trap country” does not exist as a keyword out there on the interfaces. Not yet, at least. The artist tagged the song as “country” for digital services and, when it took off, it appeared for one week on Billboard’s country chart more or less automatically. This set off a war between the robots and the industry politburo, in some ways recapitulating the drama of the early nineties, when Billboard—which had formerly ranked each chart according to often-impressionistic reports from selected record store buyers or managers—shifted to digital sales data provided by SoundScan. This transformed the industry, in no small part because quasi-objective data revealed the massive popularity of country music. Garth Brooks, up until then a well-regarded modern country singer, woke up one day to discover he was the most popular musical artist on the planet. He remains the highest selling artist of the SoundScan era.

However, the assignment of songs to given charts remains the prerogative of Billboard’s central committee, even in the streaming era. After its first week as a robot-generated country hit, “Old Town Road” was removed from said chart in a rare but not unprecedented move, ostensibly because, while it “incorporates references to country and cowboy imagery,” it “does not embrace enough elements of today’s country music to chart in its current version.” This claim gestures toward the reality of genre but no one really believes that the media outlet charged with both assessing and assuring the music industry’s profitability is being run by genre theorists, hence the exasperated lol that arose from millions of listeners who understood full well that the exclusion, despite disavowals, derived from the fact that the artist is black and goes by the name Lil Nas X, and because the song’s rhythm track and collage character signify black music, hip-hop in particular. It was shifted instead to “R&B/Hip-Hop Songs” where it promptly hit #1, reaching that peak as well on the Hot 100. It now holds the record for the most streamed song in a single week ever. Lil Nas X is motherfucking Garth Brooks, at least for now.

Nonetheless the exclusion caused predictable outcry about race, the industry, and the broader culture’s habits of racial segregation, along with the ongoing asymmetry of aesthetic appropriation. In the first instance the anger behind this outcry is inarguably justified; the history of musical genre in the United States is among other things the history of racial gatekeeping and the false objectivity of white power. But certain things complicate this story. One of them is that it is hard to construct a history of charts, markets, and genre wherein country is a privileged form simply for its whiteness. Instead, it shares with hip-hop a history of exclusion. The Billboard braintrust once possessed a longstanding hostility to country music, which before the SoundScan era was often sequestered on its own chart and not allowed onto the Hot 100, a status it shared with early hip-hop. We remember well how aggressively early MTV, Billboard’s chief competitor as a market maker in the eighties and nineties, suppressed black music, particularly R&B/hip-hop; it is rarely noted that it also suppressed country music more or less entirely. Here we might wish to ask the question left over from above, that of why record stores so dramatically underreported country sales in the pre-SoundScan era? They were selling three Garth records for any other given title in 1990 and when they got on the phone with Billboard they were all like, man, Depeche Mode’s Violator is crushing it.

Race doesn’t get us very far in answering this question. Neither does gender, given country’s tragic marketing preference for male artists. But class goes a long way. Without making any claims about the actual character of performers or fans, it seems inarguable that country music is haunted by the specter of the working class, and this again clarifies its historical parallel with hip-hop: raced in opposition, they are classed in concert — the twin musics of the white and black proletariat. Again, this reflects reality imperfectly; it is nonetheless entirely fixed in the aesthetic unconscious.

None of this tells us much about “Old Town Road” and perhaps that is appropriate. It is not clear how much there is to say about the song, which is witty and catchy and remarkably slight, as if its main goal was not to be a song but to be just enough of a song to work as a provocation. Born in Atlanta, Lil Nas X’s lyrics are about having taken his hip-hop body to the scene of the rural, the agrarian, so that as a matter of geographical and cultural force, as a matter of the labor that he does, it becomes country, “ridin’ on a tractor, lean all in my bladder.” Through this magic the lyrics (and arguably the music) are not about being country but about being country contra hip-hop, “ridin’ on a horse, you can whip your Porsche.”

“‘Old Town Road’ succeeds by trolling the entire fantasy.”

The rerelease with a hook and a verse sung by Billy Ray Cyrus doesn’t mean to offer a fuller song but a fuller provocation, an added dimension to the troll. (Please forgive me, this is the part where I coin the term trollbilly). The presence of Cyrus seems to say, you want proof of genre, here is an actual emissary, one who got famous behind the novelty country hit “Achy Breaky Heart” which just happened to be released a year into the SoundScan era and thus was able to hit not just #1 on the Country charts but #4 on the Hot 100. But Cyrus’s role is not to provide proof of genre, it is to fuck it up even more.

Cyrus delivers a verse that is maybe about, hmm, being hip-hop, “Bubble hard in the double R, flashing the rings with the window cracked”—no, wait, that’s Jay-Z from 1998. Billy Ray, born in Flatwoods, KY, has it like this: “baby’s got a habit, diamond rings and Fendi sports bras, ridin’ down Rodeo in my Maserati sports car.” The “Rodeo” gesture is genius, obviously, and I am too lazy to figure out where it is borrowed from; wherever it originates, it surely works better here. In a perfect inversion of Nas X’s verse, this is hip-hop contra country, which persists as a ghost, “got no stress, I been through all that, I’m like the Marlboro Man so I kick on back.” His country roots have prepared him to be a downtown don. But this comes at a cost; the life left behind for LA bling rises up as a nostalgia that leads us back to the hook, “wish I could roll on back to that old town road, I wanna riiiiiiiide till I can’t no more.” It would make even more sense if Miley sang it.

It obviously won’t do to say it’s a hip-hop or country song as if such a statement could have any inner truth. It is a song, rather, whose entire project is to set loose the simultaneous opposition and relation between the two genres. But here we might notice that this, uhh, unity-in-contradiction of the two genres is mediated, both in the song and more widely, by the relationship between city and country, another longstanding axis of racial and proletarian difference both real and ideological. We have now more or less arrived at the fantasy life of American genre, wherein the two great indigenous forms signify an entire arrangement of the nation in which black urban and white rural life are set against each other. No matter that this circumstance has never truly existed; it remains the dream of the nation, the nightmare from which we cannot awaken, freezing into place the two endlessly debated, endlessly ignored political communities, the black proletariat warehoused as surplus in the cores of deindustrialized cities, and the much-bruited “white working class” sharpening their resentments out in Trump country. The musical genre system more broadly has succeeded by mobilizing this world picture. “Old Town Road” succeeds by trolling the entire fantasy.

But there is an underlying puzzle, or difficulty. The country/city system has been breaking down and has transformed both genres. When it became clear, in the nineties, that the majority of hip-hop fans were to be found in largely white suburbs, the genre was compelled to make the leap from invoking country themes of the wild, wild west to actually internalizing a greater number of white artists led by Eminem and Kid Rock, both of whom were required to perform (speciously or not) their membership in the white underclass of “trailer trash” while demonstrating some degree of admiration for black authenticity, and both of whom would go on to outsell their non-white counterparts. Kid Rock’s turn to country-rock and then musical retirement basically looks from here like he just couldn’t stand to not be racist.

The collapse of the country/city binary had in some ways even more dramatic effects on country, which had depended far more explicitly on the opposition to structure the entire the genre—a trajectory that peaks with Hank Williams Jr.’s terrifying, racist, and epochal “A Country Boy Can Survive.” The prepper anthem imagines a city life of bloodless technical-managerial types unable to defend themselves from criminal predation by the urban underclass; against this, the basic subsistence skills imparted by agrarian life prepare rural whites for a world lurching toward apocalypse (Williams would remake it, now with more xenophobia, as “America Can Survive” shortly after 9/11). The song offers a world with three positions: white intellectual labor, black social refuse, and white manual labor. Only one of them will keep you alive in the social collapse to come, the song is at pains to tell us. It reached #2 on the country charts in 1982 while — as if by magic—never appearing on the Hot 100.

“Between equal genres the market decides.”

Within a decade, it would become clear that country’s main markets were also in the suburbs. Lacking the easy opposition of the high rise and the hollow, country has since then scrambled to find new locations for its old virtues, setting more and more songs, for example, at the beach or on the water. Solving the same problem in inverted form, it increasingly issues forth songs insisting that cities can be country too, in the manner of ultra-butch Brantley Gilbert’s 2011 “Country Must Be Country Wide,” a song insisting that “there’s cowboys and hillbillies, farm towns to big cities” before quoting, no surprise, “A Country Boy Can Survive.” Country has also tried, fitfully but for more than twenty years, to incorporate elements of hip-hop: in some regard by taking on hip-hop production techniques and sounds; sometimes by bringing in name-brand rappers to deliver guest verses; occasionally via “country rappers” both black and white such as Cowboy Troy and Bubba Sparxxx; more commonly by featuring rhythmically spoken interludes by white singers like Jason Aldean; and most often by letting post-rural acts like Florida Georgia Line rhapsodize, in anodyne New Country tracks, about how much they like certain hip-hop artists.

If both of these genre reformations respond to the inexorable power of market changes, they are not equal. Country approaches these as fundamentally demographic or geographical challenges that can be addressed gesturally, with blackness allowed to appear in secondary and subordinated fashion. Hip-hop, which unlike country music is not just a successful musical genre but the orienting form of black art in the United States, understands this challenge as metaphysical.

To understand the intensity of the drama, it may be useful to look to a series of recent films. After all, Lil Nas X insists his life is a movie. Get Out, BlacKkKlansman, and Sorry To Bother You, mainstays of the New Black Cinema, are distinct and even disparate in their thinking; they are also the exact same film. Well, that is an exaggeration, but they share an extraordinary and central feature. Jordan Peele’s Get Out, per its central plot device, features visibly black characters whose speech is nonetheless the speech of the wealthy whites who have purchased these black bodies as dwellings. In Spike Lee’s BlacKkKlansman, the black cop who is the film’s hero passes himself off, over the phone, as a white racist. And Sorry To Bother You, directed by the great hip-hop artist Boots Riley, features a side character played by Danny Glover — once a leader in the Black Student Union at San Francisco State that, along with the Third World Liberation Front and others, led a five-month strike to establish the first Ethic Studies Program in the nation — literally instructs black co-worker Lakeith Stanfield on how to “use your white voice” toward greater success as a telemarketer. The lead’s virtuosic leveraging of the voice sets the terms for the film, as he ascends quite literally into the penthouse of super-sellers, and thereby finds himself at once newly wealthy and at odds with an ethnically and racially diverse labor movement which nonetheless intimates that blackness is the truth of proletarian life and vice versa.

“Old Town Road,” then, emerges in a contemporary moment when there is an ongoing crisis that finds its cultural expression in the insistent and self-replicating figure of a white voice coming from a black body. In the films this figure has multiple, overlapping meanings: pure possessive whiteness; whiteness as the key to class mobility; the need, in BlacKkKlansman’s unfortunate vision, for militant blackness to take up with white state power, too weak to defend itself on its own against white racists. The red thread might be something like this: from the era of chattel slavery down to the present, there is a continuous threat that black people will be so abjected by direct and structural violence, by the race-class nexus (and by gender too, as Claudia Jones would be the first to remind us), that they will have to become white, will have to take whiteness into themselves and perform it for the white world, just to exist, if that is existence — and that this ongoing threat is again at an inflection point, as the various racisms and xenophobias ascend globally. Lee is the only one who doesn’t seem aware that the white voice coming from a black body holds this horror, is itself horror for the subjects of slavery, Jim Crow, and the Emanuel AME church shooting. This explains much about its screenplay earning the Oscar for Lee; it captures something central about the black cultural drama of the moment but for laughs and for white audiences.

“Old Town Road” does not feature this figure, and in some regard it can’t, given the media differences between cinema and songs. But it matters that the films’ conceit, their leveraging of crisis around a very contemporary efflorescence in American racism, is aural. Among other things, it insists that race isn’t phenotypical but social, a matter of what is heard, and how that is subject to disturbance. “Old Town Road” mobilizes something like the same disturbance, in a trivial sense with the black singer signifying country and the white singer signifying hip-hop, with the musical track making sure we encounter that reversal in a state of confusion. More significantly if less explicitly, it makes sure that we hear a white genre coming out of a black body—and can it be any surprise that this elicits particularly intense reactions just now?

The song insists that race is social and also deadly, that the social is deadly always and forever and a whole lot right now. But something about “Old Town Road” is also for laughs. It is not the parodically “country” lyrics, exactly, self-parody being anyway a storied country tradition. It is instead something like the giddy rush of transformations within such a slight track. It swiftly sets loose the chain or array wherein style (both form and content) is an imperfect proxy for genre, genre is an imperfect but open proxy for race, genre is also an imperfect but secret proxy for class, and the song will not let the listener settle into any of the calcified ideological positions. It insists that genre too is social while drawing forth not simply the antagonism but the unsayable unity of country and hip-hop. They stand as strange equals and for a moment there is no way of knowing which is which, though the brief sonic experience cannot evade its material conditions. Between equal genres the market decides.

All of this is a lot to lay on a song that is little more than a budget lope and minimal hook, studiously insistent on being nothing in particular. Its listeners are nothing and must be everything.

.