A right-wing wave has swept the globe in recent years. The largest country in Latin America may be next.

On October 7, in the first round of the presidential election, Brazilian voters nearly elected Jair Bolsonaro, the rabidly misogynist, racist, anti-poor, and homophobic former Army parachutist who sinisterly sings the praises of the military dictatorship of his youth. This Sunday (October 28) Brazilians voters will go to the polls again in a run-off election pitting Bolsonaro against Fernando Haddad, whose Workers’ Party has controlled Brazil for most of the last 15 years. In recent polling Bolsonaro leads Haddad 59 percent to 41 percent. If elected, he promises to arm citizens, install the military in the streets, seize land from indigenous communities and black quilombos, throw open the Amazon to mineral and resource extraction, and otherwise enforce a brutal austerity program. Many observers foresee a heightened possibility for return to military dictatorship. Most or all of Bolsonaro’s cabinet will be made up of generals and the possibility for an autogolpe, or “self-coup,” has already been hinted at by his running mate, far-right former general Hamilton Mourão.

With Bolsonaro, Brazil follows in the footsteps of nations around the world, where far right, neo-fascist, and authoritarian leaders have seized power on outrage fueled by economic and political crisis. Centrist elites have lost the confidence of large parts of the world’s population as the global economy has declined. For many years, this decline was mitigated by austerity policies and the liberation of finance, freeing up corporations to move factories around the world like chess pieces. Governments competed with each other to see which of them was most willing to drive its citizens into penury and its environment into total collapse. Since the 2007-08 crisis, however, the global economy has shown itself resistant to these methods for jumpstarting growth, discrediting the centrist neoliberal politicians associated with them. In some places, this has meant an opening for the left. But in India and the Philippines, Hungary and Turkey, not to mention the US, a new crop of authoritarian leaders has seized on the opportunity presented by crisis to exploit a rising skepticism about democracy. In economic doldrums since the end of the 2003-10 commodity boom, Brazil is ripe for such a plunge to the illiberal right.

Bolsonaro has been an extremist, though mostly marginal presence in Brazilian politics since the 1990s. His public profile grew in 2011 when he began to appear frequently on the television show CQC, proffering outrageous statements about the LGBT community, Afro-Brazilians, and women. Brazil has strict laws about verbal aggression against minorities and in 2015 Bolsonaro was fined 150,000 Brazilian Reals (around 40,000 US dollars) for statements on the program. However, in 2014, he received the highest number of votes of any state representative from Rio de Janeiro. After almost thirty years as a state representative in which he had successfully proposed only two laws, Bolsonaro’s dark star was on the rise. He was accompanied by a new far right formation including the bancada de bala, de boi, and evangélica or the bullet, pro-agribusiness, and evangelical caucuses.

Bolsonaro was not the frontrunner at the beginning of this election cycle. Once again it was former president Lula Inácio da Silva. In 2014, Brazilian elites orchestrated a soft coup, using trumped-up, legalist charges against Lula’s successor, Dilma Rousseff. They were helped by Brazil’s large media conglomerates such as Globo. While the Lula and Dilma governments were far from radical—mixing pro-business policies with increases in social programs– Brazilian capitalists and political elites retook power and had Dilma removed. This stratagem backfired, as Dilma’s successor, the conservative Michel Temer, has become the most unpopular politician in Brazilian history. As of June 2018 his approval rating was 3 percent, with an 82 percent disapproval rating.

Lula was the candidate with the best chance of filling this vacuum. Despite the corruption investigations that had embroiled him and his party, Lula was still the most popular politician in Brazil. Even as late as August, Lula held a 20 point lead over Bolsonaro. Fearing yet another win by Lula, elites turned once again to “lawfare,” or the use of legal procedure for explicit political ends. They jailed him and removed him from the race, placing him in solitary confinement and barring him from speaking with the press. Less than a month before the first round of elections, his legal options exhausted, Lula named his running mate Haddad as his party’s presidential candidate.

If Bolsonaro is the candidate of capital, he is also the candidate of crisis. Highly unpopular measures that even the Temer government could not pass are back on the table, including the privatization of Petrobras and deep cuts to social security. Bolsonaro’s platform is notoriously vague and he has avoided most presidential debates (he was stabbed at a campaign rally on September 6 and uses this as an excuse). Some outlets have compared the candidate to Trump, but Bolsonaro has not run by paying lip service to economic nationalism and he lacks the US President’s media savvy. Along with austerity economics, Bolsonaro brings a super-charged commitment to violence, which he will certainly need if he wants to force the working class and poor, already devastated by the end of the boom years of 2003-2010, to endure more cuts. Bolsonaro has proposed sending the police into the slums, or “favelas,” with “carte blanche,” and in the two weeks since the first round of voting, his supporters have engaged in hundreds of acts of political violence, including several outright killings. Bolsonaro is famous for his double-handed gun finger gesture, a symbol mimicked by his followers in photos on social media: a man become weapon, the leader as death-dispenser, both violent permission and homicidal promise.

“Many observers foresee a heightened possibility for return to military dictatorship.”

Instead of Lula’s, the vacuum was Bolsonaro’s to fill, but the parachutist needed some help before he could glide into the presidential palace. At the beginning of the campaign, Bolsonaro’s economic policies were similar to those held by the military dictatorship that controlled Brazil from 1964 to 1985: a belief in an interventionist state and protections for national industrial development. These were not the kind of pro-austerity policies to get national and global capitalists on board, nor likely to earn the favor of the IMF and other international organizations. Still trailing Lula, Bolsonaro tacked, bringing on as economic advisor University of Chicago-trained Paulo Guedes, who taught at the University of Chile during the dictatorship of Pinochet. Media outlets allowed him to slightly soften his image and circulated numerous unverified falsehoods. The U.S. foreign policy establishment, Wall Street, and Brazilian capital all threw their support behind Bolsonaro, who became the candidate of capital. The Wall Street Journal editorial board endorsed him as the “Brazilian swamp drainer.”

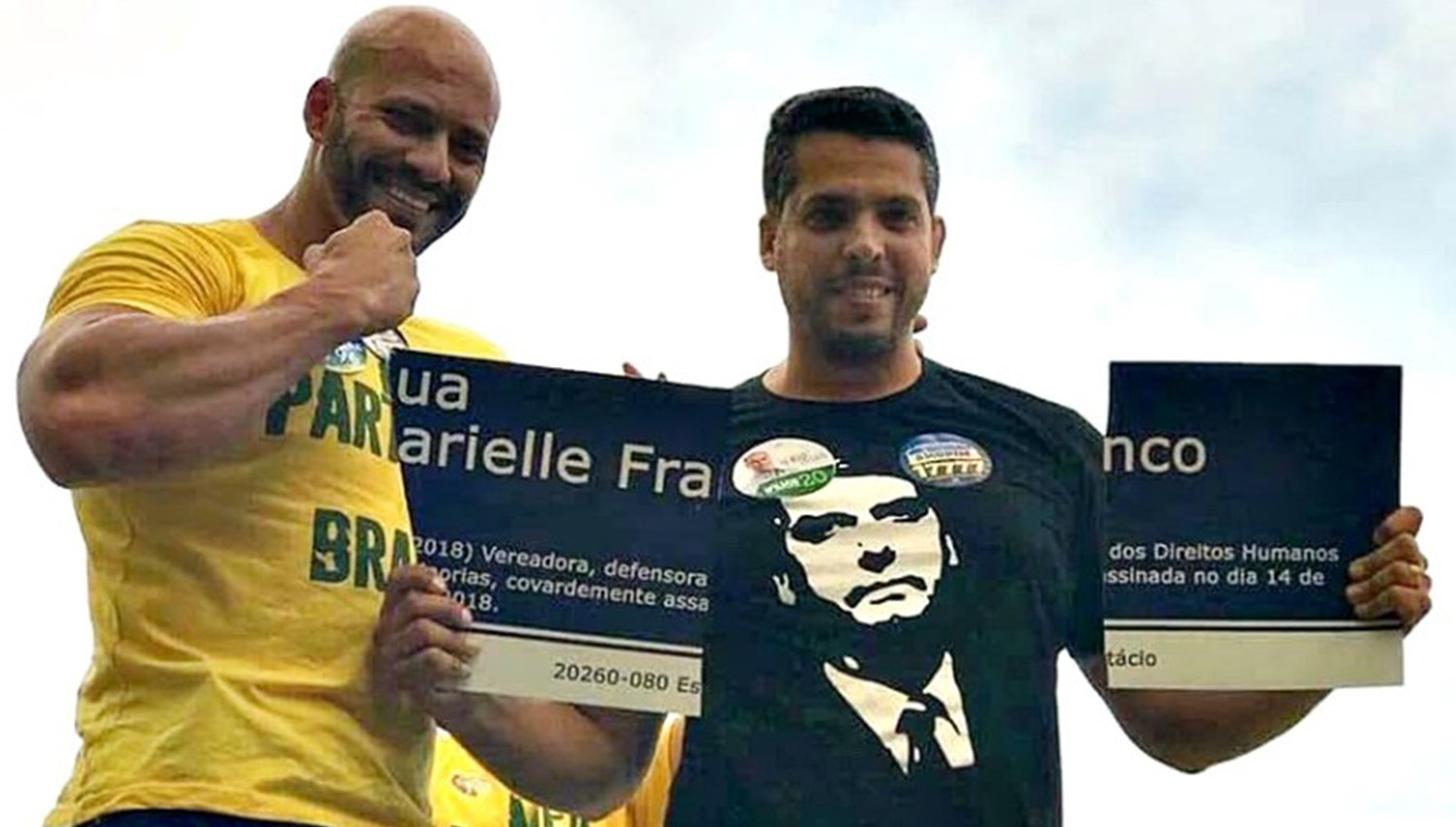

How did such a candidate achieve such backing? How did the Brazilian electorate get behind a candidate who declared that a fellow congresswoman didn’t deserve to be raped because she’s “very ugly,” who repeatedly refers to Afro-Brazilians as animals, who dedicated his impeachment vote of Dilma to the military figure who ran the center where she was tortured, who stated he will put a “final end” to all “activisms” in Brazil? How did Bolsonaro’s tiny Partido Social Liberal (PSL) exceed their polling numbers and win the second most seats in the legislature? How did candidate Rodrigo Amorim, who infamously posted on social media photos where he is defacing the memorial plaque of murdered Rio de Janeiro city councilor and black feminist Marielle Franco, become the largest vote getter among state representatives in Rio de Janeiro this year?

Beyond the current political and economic crisis, there are several other contexts which are important for understanding the emergence of a new far-right and neo-fascist movement in Brazil. First, like the United States, Brazil is a former slave society. Five million or roughly 45 percent of all slaves brought to the Americas came to Brazil, which in 1888 was the last country to abolish slavery. Like the United States, it is deeply racist, with a long history of institutional racism. Second, after the end of the dictatorship and the “transition to democracy” in 1985, Brazil never substantially modified its juridical framework. The security apparatus the dictatorship built was never dismantled, and members of the dictatorship who participated in killings and torture were never brought to justice. During the economic downturn and crisis of the 1980s and 1990s, police-linked death squads proliferated, terrorizing marginal communities into submission. These combined histories of racism and militarized public security have produced a Brazil with an extraordinary number of police killings per capita. The incomplete data tell us that police killed just over five thousand Brazilians last year. There is widespread support, even in marginalized communities, for the idea that “bandido bom é bandido morto” (a good criminal is a dead one).

“This fake news messaging…has included claims that Haddad, while governor of São Paulo, handed out baby bottles with fake penises as teats and that, once elected, he will render children property of the state, empowered to decide their gender by administrative decree.”

Bolsonaro has also taken advantage of two more recent developments: social media and the rise of evangelicals. Bolsonaro’s campaign consulted with Steve Bannon and has used a Cambridge-Analytica-style approach spamming outrageously fake news at key groups via social media. He has relied in particular on WhatsApp. Last week it was revealed that Brazilian “entrepreneurs” had created an illegal slush fund to help pay for pro-Bolsonaro fake news blasts on WhatsApp. The Superior Electoral Court is currently investigating but it is unclear if they will take action before the election. This fake news messaging, much of it deeply patriarchal, trans- and homo-phobic, has included claims that Haddad, while governor of São Paulo, handed out baby bottles with fake penises as teats and that, once elected, he will render children property of the state, empowered to decide their gender by administrative decree. Many of these messages are aimed specifically at evangelicals—a group which has grown from 9 percent of the total population in 1991 to 20 percent in 2010. While politically active for a number of years, evangelicals have turned into a key constituency in this political cycle. Evangelical and far-right groups have begun to work together to stage political events, burning effigies of Judith Butler outside of one of her talks in São Paulo, for example, and petitioning museums to cancel exhibitions of queer art work.

Polling has demonstrated that support for Bolsonaro is strongly inflected by gender and race, but also very significantly by income. Of those making five to ten times the minimum wage, 51 percent supported Bolsonaro in polling before the first round of the elections. Among those making more than ten times the minimum wage, his support was 44 percent. Bolsonaro represents a class project, as demonstrated by his deep support among the middle and upper classes who want their property and profits secured.

The most likely outcome of Sunday’s election is a Bolsonaro win. Exactly how bad things will get once he takes power is anyone’s guess, but the reality is that almost any nightmare is possible. For the first time in almost forty years, the far right will have taken control of a large Latin American country. Bolsonaro’s rise has not gone unchecked, however, and any nightmare, no matter how terrible, can be dispelled by the light of day. Women have mobilized in large numbers against Bolsonaro, organizing many events, including the massive Ele Não (Not Him) protests on September 29 and October 20. Afro-Brazilians, indigenous communities, anarchists, and students have also begun to organize. Any successful resistance to Bolsonaro and the far right must by necessity draw upon and deepen the autonomous struggles and uprisings seen since 2013, and break the hold that Lula’s Worker’s Party exerts upon the Brazilian left. Anti-state and anti-capitalist autonomists will also have to bear in mind the limiting effects of the crisis. Unlike the 1960s, when the military dictatorship was able to ride the postwar boom to economic growth, Bolsonaro’s government will be a government of austerity. Here there is a potential weakness but also an additional danger. If his government cannot supply any kind of economic stability, it may lose its luster for some non-core supporters, especially if confronted and pressured by a strong or at least visible and vocal autonomist movement. The danger is that, without an economic revival, austerity can only stay ahead of dissent through state-linked and permitted violence or a military takeover. Both are nightmares which will be difficult to wake from and which Bolsonaro’s government is terrifying well-positioned to enact.