Canada wants new migrant prisons but is facing resistance.

Over the past year, the struggle to stop the construction of a new migrant prison in Laval, Quebec has received an increase in mainstream media coverage and growing buzz around movement spaces in Montreal. While this has helped spread the word about the proposed new construction, little has been written about the context it emerges from.

When discussing Canada’s current migrant prisons, there’s often confusion about how to refer to them. The government has used many names for them—immigration holding centers, migrant detention centers, immigration prevention centers—but regardless of the government’s branding, they are prisons. Run by the Canadian Border Services Agency (CBSA) and staffed by private security (in Laval, they use Garda), these prisons detain migrants indefinitely and without charge.

Today Canada has three federal migrant prisons: one in Toronto; one in the Vancouver airport; and one in Laval, the largest in the country. In addition to these facilities, the CBSA has deals with provincial governments that allow them to imprison migrants in provincial jails. In Ontario, for example, most imprisoned migrants are held in provincial jails, while in Quebec, most are imprisoned in Laval. In 2017, Canada detained close to six thousand migrants between both types of facilities, including 162 minors.

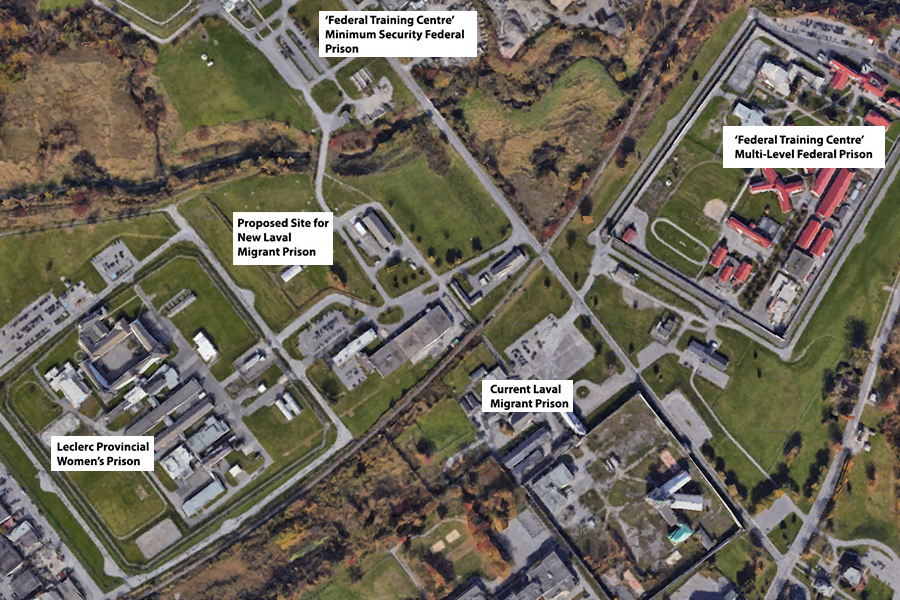

The proposed prison is planned to occupy an empty field next to the current Laval facility and eventually replace it. The new building will hold 158 migrants and refugees, about 15 more than the existing facility. Both the current prison and the proposed site of the new prison are located on a street called Montée Saint-François, in an area that houses several other prisons.

This new facility is just one part of a $138 million plan the National Immigration Detention Framework (NIDF), that the government announced in 2016 following a period of sustained resistance against the imprisonment of migrants.

While struggles against migrant detention have gone on for years, 2011 saw migrants detained by the CBSA organize hunger strikes in provincial jails across Ontario. These strikes continued periodically over the next several years, with over 180 migrants participating in 2013. Building on these actions, a new hunger strike was carried out in 2016, with mobilizations around the country in solidarity. There was a lot of pressure on the government to respond to this wave of agitation, especially after the death of several migrants in CBSA custody during the same period. Over 60 detained migrants participated in the 2016 strike, which amplified years of mobilizations and received a high level of outside support.

The government’s response to this pressure was the NIDF plan. But instead of ceding to the hunger strikers’ demands, most of the budget was dedicated to building two new migrant prisons—one is in Surrey, British Columbia, scheduled to open in a few months and replaces the CBSA’s Vancouver airport facility; the other is the proposed new prison in Laval. They would strengthen the same detention system the strikers were fighting against.

A year after the NIDF was announced, the government hired two architecture firms, Lemay and Groupe A, to design the new Laval prison. A look at the documents the government provided to these firms (and published online) clarifies the objectives behind constructing a new facility in Laval. The government specifically requires that the barbed wire fencing around the prison be covered in foliage to limit the “harshness of look,” that the iron bars over the windows be “as inconspicuous as possible to the outside public,” and that the children’s area be bordered by what they call a “visual abatement” to make sure that no one outside can see the imprisoned children. Essentially, it’s the same prison with a nicer-looking façade.

The National Immigration Detention Framework also sets aside money for something the government calls Alternatives to Detention (ATD). These programs only make up about 4 percent of the budget, but have been a central part of its marketing as a supposedly humane approach. In reality, these “alternatives” are simply existing carceral technologies pulled from different corners of the criminal justice system. They include electronic ankle bracelet monitors, electronic monitoring through cell phones, the creation of halfway houses, and a parole or probation-like program for migrants. Previously, the only options were detaining or releasing people under limited conditions, but these new methods allow the government to expand its capacity for surveillance and control of migrants outside prisons.

“Essentially, it’s the same prison with a nicer-looking façade.”

Many migrants detained in Ontario went back on hunger strike following the announcement of the NIDF, but the government continued to ignore their demands, instead using the call for better conditions as an opportunity to further expand the regime of migrant detention. In fact, the number of migrants detained by the CBSA increased by over 30 percent in 2017, the first year that the NIDF took effect, and the government pledged to also increase deportations by over 30 percent. The public image of the NIDF as a more humane approach to migrant detention allowed the government to shift attention away from the question of why migrants are being put in prison in the first place, a question many people started asking during the 2016 hunger strikes in Ontario.

After the announcement that the government was going to build new migrant prisons and expand the deportation apparatus by implementing the ATD, resistance outside the prison walls started to heat up, particularly in Quebec. Organizing began when members of Solidarity Across Borders (SAB), who had either been detained or had family members detained in the current Laval facility, came together to discuss opposition to the new prison. But the most recent wave of action started in February 2019, when a group called Ni Frontières, Ni Prisons organized a demonstration in Montreal against Lemay, one of the aforementioned architecture firms designing the new building. Over a hundred people marched to Lemay’s headquarters, where a wide range of people gave speeches, including people who had been incarcerated in the current Laval prison, and people from the local housing committee who drew connections between Lemay and the ongoing gentrification of the neighborhood.

Around the same time, the government began requesting bids for the prison’s construction contracts. Companies wishing to bid were asked to show up for a site visit to ask questions of the CBSA and see the location. On February 20, about 25 people blocked the road leading to the site, preventing the visit from happening. A few days later, Ni Frontières, Ni Prisons launched a call-in campaign targeting the companies publicly bidding on the construction contract. Supporters were asked to call, fax, or email the companies and tell them not to bid on the contract. Callers reported frustrated responses from the companies, which pleaded with people to stop calling and to take their information off the internet. Following these actions, the CBSA extended the bidding period, putting the project two months behind schedule.

In April, Solidarity Across Borders held a demonstration at the current Laval migrant prison to commemorate the one-year anniversary of the violent deportation of Lucy Granados, a member of the Non-Status Women’s Collective. Demonstrators marched to the site of the new prison where speeches were given urging SAB members to “push back against this project, to fight, and to ensure that it never sees the light of day.”

Together, Solidarity Across Borders and Ni Frontières, Ni Prisons have spent the past year organizing dozens of information sessions in collaboration with groups across Montreal and Laval, building a wide network of opposition. On May 14, Solidarity Across Borders released a statement signed by over 80 organizations opposing the new migrant prison: “We want a world without prisons or colonial borders; a world in which people can decide where to move and where to stay; a world based on mutual aid, not fear, precarity, and exploitation.” Signers pledged to “work in our own ways to stop” construction.

Reflecting this attitude, a campaign of sabotage has simultaneously been carried out against companies involved in the new prison’s construction process, starting in April 2018 when a group calling themselves the “anti-construction crew” released thousands of crickets into Lemay’s headquarters in Montreal.

These actions have heightened in 2019. In January, a company called Loiselle, which was involved in soil remediation of the new construction site, saw its headquarters covered in spray paint with slogans denouncing the migrant prison. This past March, two condo projects developed in collaboration with Lemay were attacked; one had its windows smashed and the other was covered in paint. And in April, Lemay’s headquarters were locked overnight. Locks were glued, doors were u-locked together, and electronic keypads permitting access by key cards were destroyed. Lemay’s garage doors were blocked by a combination of spike strips and smoke bombs rigged to go off when the doors opened. Communiques about both attacks condemned the company’s involvement in designing the new prison.

On May 1, the Convergences des Luttes Anti-Capitalistes (CLAC) held a special “No Borders” May Day demonstration, which also marched to Lemay’s headquarters. Organizers handed out flyers highlighting Lemay’s role in profiting off the new migrant prison, while multiple people threw projectiles and broke most of the windows on the primary entrance to the building.

Actions have continued into the summer, including the anonymous torching of the car of Lemay’s vice president, the planting of 490kg of oats, peas, and fava beans across the proposed site of the new prison, the destruction of a vehicle owned by Englobe, the company that oversaw the site evaluation process, a Solidarity Across Borders press conference at the site after the general contractor, Tisseur Inc. was announced, and most recently an on-site public picnic where participants hit a piñata decorated in the designs for the new prison.

Recent media attention around immigration has largely focused on the American context, with the Canadian government’s own approach to migrant exclusion receiving far less scrutiny. Media conversations about Canada and migration have largely focused on the Liberal government’s admission of Syrian refugees, or on asylum seekers crossing the border on foot from the US. Though it might be tempting to place the growing struggle against the new Laval prison for migrants in this context, the Canadian government’s migrant prisons predate both of these trends; in fact, the story of Canada’s border enforcement stretches over centuries.

“But just like “humane” prisons, we’ve seen alternatives to detention before and what they actually mean is more people under new forms of state control, for even longer periods of time.”

Canada’s borders were largely established to enclose the territory it stole from Indigenous peoples and to regulate the labor force within those territories. Canada’s prisons emerged alongside those borders, and have been a part of the ongoing genocide against Indigenous peoples ever since. The earliest jails held runaway slaves (both Black and Indigenous), and a hundred years ago, the department charged with overseeing migration was called the Office of Immigration and Colonization, which rounded up and deported tens of thousands of unemployed migrants during the Great Depression. The way Canada has enforced its borders has changed over time, but the role these borders play in controlling labor has remained, and this control has always been enforced along racial lines. Canada’s contemporary economy relies more and more on the existence of a large pool of precarious, highly exploitable workers from the Global South, and current policies around migration reflect Canada’s interest in maintaining that labor pool.

The transition to policy that facilitated this type of economic structure began in the 1960s, when Canada shifted away from its previous explicitly race-based migration policy. The replacement of the simplistic, “whites only” system with a more complex exclusionary framework, with tighter internal border control measures including multi-tiered status and migrant detention, led to a significant expansion of the deportation apparatus by the 1990s.

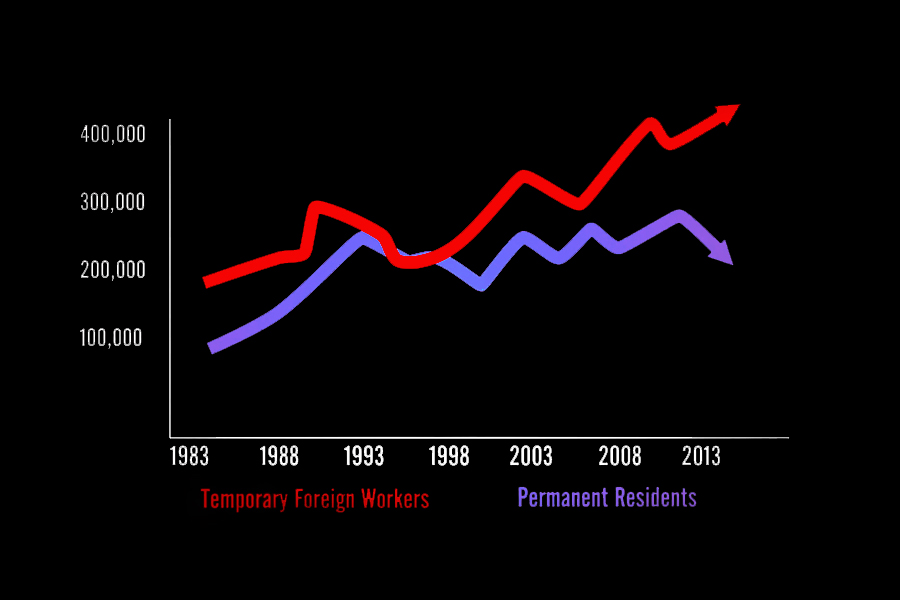

In 1966, the Canadian government also created the Seasonal Agricultural Workers Program, the first program to grant temporary status to migrant workers. Over the next few decades, migrants began receiving temporary status at higher and higher rates. Since then, this tendency has escalated. Between 2002 and 2012, the number of temporary migrant workers admitted into Canada tripled. Today, over two-thirds of people granted status to live and work here each year receive some form of temporary status. Most will never have the option to stay permanently, and their status is tied to the whims of their employer. Programs like this have become integral to Canada’s role in maintaining the flow of wealth from the Global South to the Global North. Migrant workers are accepted by Canada in great numbers, have their labor exploited at extreme levels, and generate huge sums of money for the Canadian economy, before they are either kicked out or forced into attempting to remain clandestinely.

Over the past decades, various forms of permanent status have only become harder to attain. Between 2000 and 2008, the percentage of migrants granted Canadian citizenship dropped from 79 percent to 26 percent. Refugee status, permanent residency, and family sponsoring programs have all tightened up significantly. While in some senses the border may seem more permeable, with more people entering on visitor visas than ever before, the internal infrastructure to deport and detain migrants has been significantly expanded and emboldened.

As temporary status becomes ever more pervasive, as more refugee and permanent residency applications are denied, Canada’s deportation apparatus continues to expand. From 2010 to 2013 alone, the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA)’s “immigration enforcement” budget doubled in size. The modern deportation apparatus effectively works as a mechanism to enforce the growing precariousness of labor, hunting down migrants once their status has expired or been denied.

The CBSA is currently able to detain, at the discretion of its employees, any migrant going through the immigration and refugee process, including children. Anyone deemed to pose the risk of not showing up for a hearing or deportation can be imprisoned. This can include people denied refugee status, people detained upon arrival (while their applications are being processed), migrants facing deportation, workers who’ve acted outside the terms of their visas, people held on “security grounds”, and many others.

The violence of Canada’s border enforcement stands in stark contrast to the government’s marketing of the National Immigration Detention Framework (NIDF). But it’s not as if the idea of more “humane” carceral strategies is anything new. Ever since the Quakers introduced the concept of incarceration as a replacement for public corporal punishment, Canadian prisons have always claimed to be humane and rehabilitative. Historically, just as with the NIDF, this branding becomes more pronounced after moments of resistance inside the prison system. Commissioners come in, make recommendations, and things get even more “rehabilitative” for a period of time.

“Alternatives to detention and more humane prisons are only a gateway to prison expansion.”

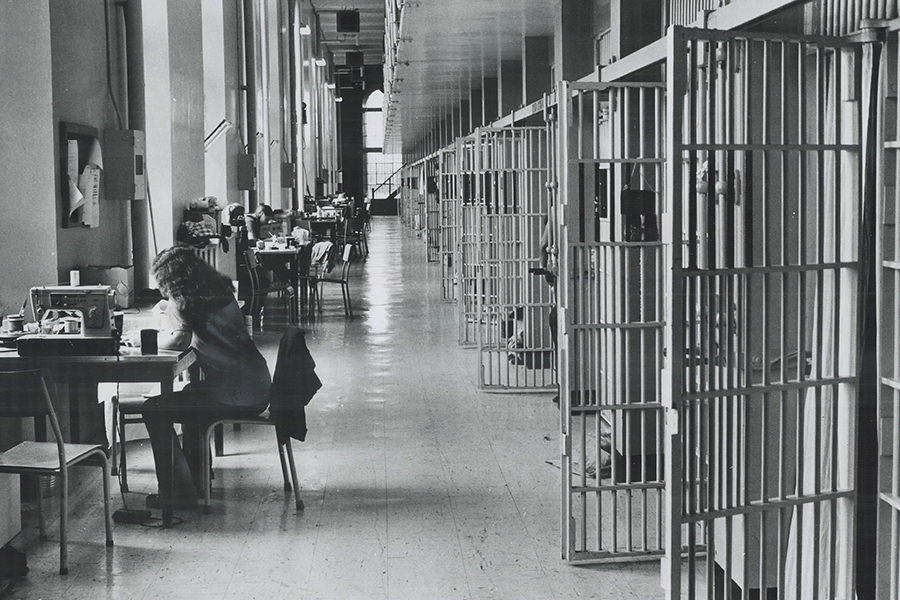

One particularly interesting example in this history is in the women’s federal prison system. The Prison for Women in Kingston opened in 1934, and for decades was infamous for the terrible conditions and brutality faced by the prisoners, as well as for locking women up far away from their support systems. Commission after commission recommended it be closed down until 1995 when there was a spontaneous moment of resistance from the women inside. As was standard practice at the time, the riot squad marched over from Kingston Penitentiary, the men’s federal prison across the street. They beat the women prisoners, cut off their clothes, sprayed them with chemical weapons, and locked them back in their cells. What was unusual was that this particular incident was caught on tape and leaked to the media. Public outcry ensued, a commission was convened, and even more recommendations were made.

The resulting 1996 Arbour Report greatly accelerated the process of shuttering the facility. The Prison for Women in Kingston was quickly closed and five regional federal women’s prisons opened across the country to take its place. These new prisons were billed as more humane, with curtains on the windows and guards who didn’t wear uniforms. Women would be closer to their families. There would be no maximum security wings.

Within a decade, Correctional Services Canada had come up with excuses (usually in the name of “security”) to build maximum security wings and segregation cells in each federal prison for women. Guards were back in their uniforms, and new surveillance technology was installed.

Women were regularly moved from wing to wing to disrupt relationships of solidarity that might be built. Yards got smaller as the number of cells increased. The number of women incarcerated skyrocketed, as judges felt more comfortable sentencing women to time in “humane” facilities closer to their homes. Indigenous women especially were imprisoned at higher and higher rates, filling the cells in these prisons.

The aftermath of the Kingston facility’s closure shows the ramifications of “more humane” approaches to imprisonment. As the Termite Collective wrote in 2015, “Well-meaning, but quickly co-opted, rehabilitative policies actually tend to disguise the harmful and punitive effects of the Canadian penal system.” Now, the government is trying to use the same process vis-à-vis the immigration system with the construction of “more humane” migrant prisons.

A similar dynamic can be traced out in the Alternatives to Detention (ATD) programs, which the government claims will help reduce migrant detention. Staffers at the John Howard Society (JHS), a non-profit which was awarded almost $5 million to implement the new “Community Case Management and Supervision” program for migrants, have even described these programs as a form of prison abolition. But just like “humane” prisons, we’ve seen alternatives to detention before and what they actually mean is more people under new forms of state control, for even longer periods of time.

First let’s look at bail and parole programs. Originally introduced in the early 1900s by the Salvation Army (who are still involved in bail and parole programs and act as the other non-profit alongside JHS to provide new ATD programming for migrants), bail and parole programs involve meetings where officers ask questions about participants’ daily lives, ask for bank statements, doctors notes, receipts for purchases, or order them to complete a urine test, among other things.

Bail and parole quickly became ways for the prison system to further control and surveil people. Participation in supposedly supportive programming has become a mandatory part of prisoner release plans, and parole revocations (when someone is sent back to jail) are often caused by reasons as vague as “lack of transparency” with one’s parole officer. Similar to the CBSA’s ability to arbitrarily detain migrants, parole conditions vary from case to case and are far more intrusive and restrictive than anything that tends to get turned into legislation.

Originally conceived by prison reformers looking to support people released from prison with nowhere to live, halfway houses have also been co-opted by the prison system to provide ways of extending people’s sentences. In the last two decades, the majority of people released from federal prison have been mandated to spend a portion of their sentence in a halfway house. Conditions in halfway houses have become more and more restrictive, often with strict curfews and visitor approval processes, and the slightest sign that someone isn’t obeying the rules can get them thrown back in prison.

This seems like the environment we can expect from the John Howard Society’s new “community supervision” program for migrants. When asked in a radio interview what would happen to people who, for whatever reason, didn’t show up at one of their programming meetings, Kassandra Roy, the spokeswoman for the John Howard Society’s ATD collaboration with the Canada Border Services Agency, said “I can’t say what we’re specifically mandated to do but […] some of the individuals referred to us are under release conditions so it would be similar to […] parolees. […] We may need to contact authorities to try and locate the person if we feel that the risk they’ve absconded is legitimate.” Just as parole pretends to be about rehabilitation but in fact expands incarceration and surveillance, “community supervision” only serves to fuel deportation.

So far, the bulk of the money set aside for new ATD programs has gone to JHS, which already runs halfway houses and parole programs within the criminal justice system. The CBSA believes this makes them qualified to run programs for migrants, and has already rented beds in existing JHS houses as part of ATD. Under the guise of “support,” migrants will be forced to agree to a release plan before exiting a migrant prison. These plans could include mandatory attendance in a 12-step program, therapy, or meetings with social workers, as well as mandatory “check-ins” with John Howard Society staff and CBSA agents.

Though JHS claims their role is to support migrants awaiting decisions on their cases and to transition them out of detention, this support comes in the form of surveillance and monitoring of people’s behavior on behalf of the CBSA, and these transitions often end in deportation.

The ATD also includes funding to institute electronic monitoring that utilizes voice biometrics and GPS reporting connected to the user’s cell phone. Migrants forced to follow this path are required to call the CBSA on a regular basis, state their name, and read out a sentence multiple times. Participating cell phone companies use voice biometrics to identify the caller’s voice and cell tower technology to identify the location without requiring a CBSA official to be on the line. Although the CBSA has long forced people to regularly call and check in while awaiting a decision for refugee applications, deportation proceedings, or other changes in status, this new program applies biometric technology to make surveillance even easier to carry out.

The final ATD program in the NIDF is the introduction of ankle bracelet monitors. Ankle monitors have a long history in the criminal justice system, dating back to their experimental use in the British Columbia prison system during the 1990s. In the immigration system, the precedents are more recent. Among the Arab and Muslim men imprisoned under the longstanding Security Certificate program in the early 2000s, some were able to be released from indefinite prison sentences on the condition that they agree to pay out of pocket to wear the intrusive, expensive, and stigmatizing ankle bracelets. One of them, Mohammad Mahjoub, later decided to return to prison rather than subject his family to the heightened surveillance his release brought them. This technology is now being forced on migrants in Toronto awaiting answers on their immigration applications.

“Let’s get together and stop the construction of this prison, and build a future free of borders and prisons.”

Alternatives to detention and more humane prisons are only a gateway to prison expansion. No matter the intentions, reform expands the carceral system, whether by giving it more tools or by increasing the number of people trapped in the system. This is particularly relevant in the context of current changes to migrant detention, where the language of prison reform is front and center. Let’s not be fooled into thinking that this is a move toward the kind of world we want to see.

It’s impossible to talk about migration in Quebec without talking about the local context. Over the past few years, movements to intensify the exclusionary nature of the immigration system have become mainstream, gaining widespread support throughout the province. According to a recent poll, over 70 percent of Quebec respondents now agree that “there are too many immigrants coming into this country who are not adopting Canadian values.” As anti-immigrant sentiment continues to grow, attacks against racialized people are increasing, and racist, anti-immigrant ideas are becoming more clearly reflected in electoral politics.

After winning the last provincial election, the relatively new right-wing party Coalition Avenir Québec (CAQ) moved quickly to cut immigration levels. They also threw out over 18,000 skilled worker applications, designed new mandatory language and “values tests for migrants, and invested in a system allowing companies to directly choose which migrant workers may get accepted (described as “Tinder for immigration”). At the same time, the CAQ is pushing the federal government to loosen regulations, so companies in Quebec can bring in more temporary migrant workers to fill over 120,000 current job openings.

But most of the changes being introduced by the CAQ are versions of changes previously made within the federal system. In 2008, Canada threw out 300,000 skilled worker applications. In 2015, the Express Entry System was introduced, which already allowed companies to more directly choose which migrant workers get accepted (described as a “dating site” for immigration). And for decades the federal government has been reducing the number of people getting permanent status, in favor of temporary migrant workers.

Fighting against the rise of the far-right in Quebec needs to be more than a one-pronged struggle against newer racist groups on the streets. It must also include sustained resistance toward racist structures that the anti-immigrant right readily exploits and is now attempting to move beyond.

As the “anti-construction crew” wrote in their 2018 communiqué after releasing thousands of crickets into the Lemay headquarters, “We understand a fight to stop this new detention centre from being built as a fight based in anti-fascism, as part of the fight against white supremacy. We seek to connect our actions to those of other people in our communities, both near and far, who are also fighting white supremacy and the rise of the far right.”

Right now, migrant detention, surveillance, and deportations are expanding. But there is no ethical past to look to in Canada’s border enforcement. Canada’s approach to migration has always been shaped by its white supremacist foundations, as manifest in the “None is Too Many” policy toward Jewish refugees fleeing the Holocaust, the “Continuous Journey” policy toward migrants from Asia, the Chinese Head Tax and Exclusion Act, and the campaign to prevent, discourage, and sabotage Black migration. Instead of looking back to false histories, we must work towards anti-colonial and abolitionist futures.

When the US introduced its own “alternatives to detention” regime for migrants over a decade ago, many migrant justice NGOs supported the plan, which was presented as a way to reduce migrant detention. Years later, when it became clear that the number of migrants held in detention facilities wasn’t going down, several NGOs came out against the alternatives, but it was too late—they were already fully implemented. We are in a moment where resistance is more possible than it might be in the future, where the changes currently being proposed are still new and unentrenched. The present is always a good place to fight from.

This struggle against the new Laval prison and the rest of the NIDF must be part of a long-term strategy of dismantling Canada’s deportation apparatus and ultimately putting an end to the enforced precarity so many migrants experience today. Borders and prisons are fundamentally about domination and control, and are entrenched parts of the white supremacist, colonial, patriarchal, capitalist system under which we live. Let’s get together and stop the construction of this prison, and build a future free of borders and prisons.