In Hereditary and now Midsommar, horror is family.

Tolstoy famously opened Anna Karenina with the truthy formula “All happy families are alike; unhappy families are each unhappy in their own way.” It took well over a century for someone to call bullshit on this properly, and it was not only a communist feminist who did it, but one who uncritically revered Tolstoy for most of her life, publicly relating to him (in her words) like a “loyal wife.” “It’s a great first sentence,” concedes Le Guin in “Happy Families.” “It sounded good.” So many families, after all, are extremely unhappy, and this extreme unhappiness feels unique, because its structural character—like the structure of capitalism—is cunningly obscured from view. But, she demands: “These happy families he speaks of so confidently in order to dismiss them as all alike—where are they?” The question gives me shivers—where are they?—because I know the answer: they’re in the future, hinted at in books by Le Guin, part of history as yet unwritten. They nestle latently in the present, in nooks and crannies where, against all odds, people are successfully manifesting the queer care commune. And, as such, they aren’t exactly “families.” But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Le Guin herself grew up “in a family that on the whole seems to have been happier than most.” That’s precisely why, she writes, “I find it false—an intolerable cheapening of reality—simply to describe it as happy.” To her, a veteran of real happiness, the phrase “happy families” travesties “the enormous cost of that ‘happiness,’” implying that happiness is ordinary, unremarkable, and easily won. To be incurious about happiness, charges Le Guin, condemns us to miss its dependence upon “a whole substructure of sacrifices, repressions, suppressions, choices made or forgone, chances taken or lost, balancings of greater and lesser evils—the tears, the fears, the migraines, the injustices, the censorships, the quarrels, the lies, the angers, the cruelties.” Happiness, as those of us assigned to so-called reproductive labors on this earth know all too well, is a clumsy art, a messy and even bloody team effort; an unremitting and glitch-riddled relational technics.

Le Guin’s essay performs a devastating read on Tolstoy, showing how his zingy opener is really merely an apothegmatic capitulation to the commonplace yet beguiling notion that unhappiness is more interesting, more worthy of inquiry, than happiness. It’s not that Le Guin doesn’t understand the reflex: “Some critics are keenly on the watch for happiness in novels,” she notes, “in order to dismiss it as banal, sentimental, or (in other words) for women.” Still, Le Guin rightly demands better of her beloved novelist, ridiculing the implication that Tolstoy personally knew “numerous happy families among the Russian nobility, or middle class, or peasantry, all of them alike.” She is also, by the way, adamant that “a family can be happy.” Yes, families can be happy, she maintains, poker-faced and only possibly joking, “for quite a long time—a week, a month, even longer.” Happiness is not a myth. That is why it matters that Tolstoy’s opening line is a lie. The great Russian knew, insists Le Guin, “what happiness is—how rare, how imperilled, how hard-won. Why he denied his knowledge in the famous sentence, I don’t know.”

I grew up in a white-collar, white, multilingual European nuclear family that on the whole seems to have been unhappier than most. I fought both my parents like an anguished zoo animal from the age of twelve or so, and fled that household as soon as I could, hoping to escape, even if just partially, the mind-warping pain of the majority of the relationships it housed. I have returned physically as a visitor to the house three or four times (it is only Dad who lives there now), but basically I have never gone back. My brother, for his part, stayed behind and became, among other things, uncannily familiar with the paramedics he would have to telephone, alone, during the worst years, to report yet another apparent maternal suicide attempt. I wish that he had fled too.

There were many, many moments of immense joy in the early years: moments mainly sutured in my memory to things like sun cream, ice cream, books, trees, pets, performances, mountain animals, McDonald’s, lakes, seasides, swimming pools, and sand statues (complete with seaweed pubic hair). I remember the joy of constant drag and dressing-up, the ad-hoc “plays” my sibling and I, in costume, would inflict on passers-by: we, the manifestly queer and non-procreative polymorphs the universe saw fit to draw from the loins of a man uniquely anxious about his immortality via offspring. Daddy was fatter, and cuddly, when we were young; his bewildering childishness, competitiveness, and spite almost amusing. Mummy hadn’t yet given up on life. I remember with affection our sofa, on which we would fart, quip, and sass one another while watching a family-favorite VHS cassette (Four Weddings and a Funeral); the breakfast table, where in-jokes, wit, camp, improv, and hilarity would flourish. There were even some moments of joy, heartbreakingly, during the hell-years. And actually, to be honest with you, despite the dozens of pronouncements I have made since 2003 or so, of true and final and “forever” estrangement, until recently, I think I never fully stopped trying to get through to them—to make happiness possible again.

I am not going to try to explain here what “went wrong” (as people like to put it). Suffice to say, for a lot of the time none of us (except Dad) wanted to be alive. My dad taught both his children by example to treat Mum with contempt—and this, I later realized, was of course also a profound form of contempt for us. Of the innumerable cutting quips generated over the years by this man’s delectable talent for cruelty, perhaps the pithiest is one he typed in a wink-wink nudge-nudge email to my partner, five years ago, calling me an arrogant know-it-all and seeking to discredit my testimony that I was raped, age thirteen, by a schoolboy I was in love with: “Rape is good for the feminist cv.”

To do full justice to the pain I’m talking about would be beyond the remit of this essay. I will not, whatever I imagine to the contrary, have exorcised it simply by writing the above paragraphs. I will burn a cord this weekend, with my friends, and meditate, once more, on letting go. But my suspicion is I cannot, in the end, stuff all my hurt into a sacrificial body and watch it go up in smoke. Disappointingly, I can still sense a wide gulf between my soul and the wisdom Katherine Angel vouchsafes in her new book, Daddy Issues (2019), when she says: “The anger and rage we might feel towards a father . . . is not something we can expel, once and for all, and nor does it yield a clear solution. Rage has instead to be folded into everything else we may simultaneously feel; it does not simply burn itself out.”

At one point, in a surreally neat illustration of our core dynamic, every one of the members of the nuclear unit who aren’t Dad—me, my brother, Mum—were simultaneously in the care of geographically disparate medical institutions, dealing with his fallout. And at one point, I kid you not, two doorways, upstairs and downstairs, were sealed up so that the house was partitioned down the middle—half him, half her—like some kind of parody of a Harold Pinter play; this being my parents’ dead-serious idea of how to do a divorce. If you sleepily autopiloted downstairs from bed, thinking to get breakfast in the original kitchen, forgetting the new addition of its mirror-double (a kitchenette), you’d literally bang into a wall. To be precise, you’d crash into a flimsy makeshift partition, behind which you could hear, in progress, the ghosts of breakfasts past.

In other words, I know the family not to be a benign “default” situation. I’ve always known. I’ve known it even though most of the movies I’ve ever seen, indeed most of the movies ever made that feature families, and all bourgeois novels by definition (especially Tolstoy), depict, or think they depict, bad things happening to a self-evidently good thing. The family, for whatever “extraneous” reason, suffers; the family recovers. The family must go on (and on, and on)!

No, long before I first heard of the historical Gay Liberationist demand to abolish the family, I knew this to be bogus. Long before I ever read Friedrich Engels, Shulamith Firestone, Donna Haraway, Hortense Spillers, or Gayle Rubin on the purposes of the private family under capitalism, I already knew—I knew—that the family is not an innocent organism upon which traumatic events descend from the outside. And more than any filmmaker I’ve come across, Ari Aster—the director newly famous among the peddlers of Tolstoyan truism for his horror debut Hereditary (2018), and now summer hit Midsommar (2019)—knows what I’m talking about.

Some might contend that all of us already secretly know. This is Tony Williams’s argument, in Hearths of Darkness: The Family in the American Horror Film, which shows popular horror flicks to be vehicles of mass anti-family desire. In the short horror film Ari Aster made in 2010 and submitted with his thesis—The Strange Thing About the Johnsons—the peaceful facade of an affluent African-American household is destroyed from the inside by years of incestuous sexual abuse, with the twist that the perpetrator is the son, preying upon and raping his father, before the son is eventually bludgeoned to death by the mother. (“The color of the family isn’t important,” says Aster in an interview, implausibly.) Here and throughout the family-slasher canon, horror pretends to worry nationalistically about threats to the family while, in fact, palpably blaming it for the tortures it endures and indulging every conceivable fantasy of dismembering and setting fire to this private nuclear unit.

I am certain that Hereditary and Midsommar are about the family, and the desire to escape it. Written back-to-back, they flow from the same thought, albeit a thought Aster might himself not fully understand. Although one movie nominally focuses on destroying the family from the inside (via murder), and the other, on preventing it from ever coming about (via breakup), together they represent parallel attempts to express a single perhaps inexpressible thing that Aster wanted to disclose.

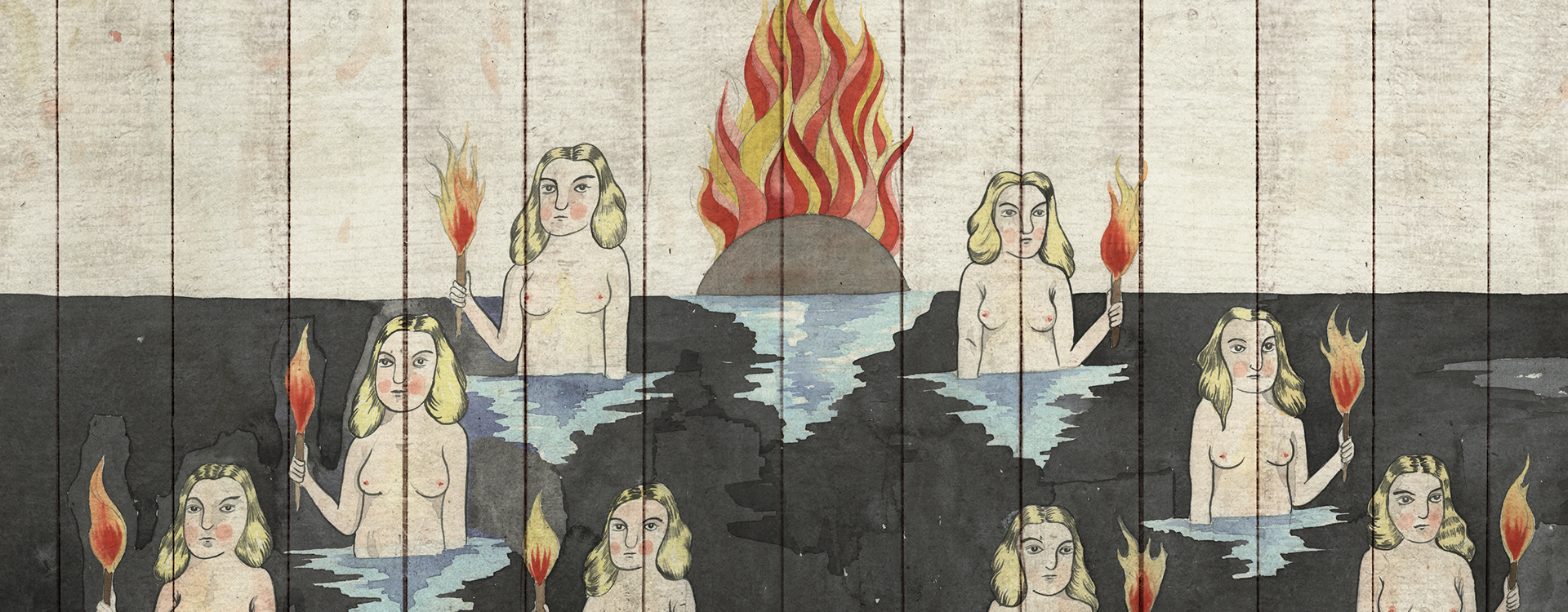

This also explains why, in many formal ways, they are substantially the same movie. They both begin with parental death: in Hereditary, the death of the secretive and cold family matriarch, Ellen, unlooses demonic forces upon the nuclear family of her daughter, Annie. In Midsommar, protagonist Dani travels to a Swedish pagan commune the summer after her sister kills herself and their parents. Both films also end with a ceremonial crowning: in Hereditary, Ellen’s grandson, Peter, is crowned the demon Paimon, and in Midsommar, Dani becomes the May Queen, at the culmination of an ecstatic nine-day Midsummer festival. Along the way both films seem to open otherworldly portals to their own powers of horror by staging moments of facial ultraviolence (a head ripped off by a collision with a utility pole, a head sawn off with string by its owner, a face crushed by a mallet). To abolish the family, these images seem to whisper, would be to abolish the self, to unmake one’s very face. That process could, potentially, be as beautiful as it is terrifying.

As well as repetition, however, the two tight-knit films also form a progression. I experienced the second as a kind of thwarted utopian daughter to the first: beginning in that same sombre color palette, but then struggling and breaking away, into the flowers and sun. But that commune around the maypole is—alas!—one in which the family hasn’t so much been abolished as held in suspension. Nevertheless, I think it’s helpful to recognize that the first film is a straight inquiry into the private nuclear household, while the second abolishes it from the beginning, quickly transporting us to a society where everything that is inflicted upon one body is ritually experienced by all bodies, in a radical sharing of affect.

The central fact about Annie, the protagonist of Hereditary, is that she’s an unwilling parent. The impossible organization of life she faces is the same one feminist artists have criticized for centuries: a world that renders mothering and making art mutually exclusive. At bottom, all Annie wants is to be alone with her miniature model-making. Her ostensible complaint is that no one in the family takes “responsibility for anything,” but the person this is truest of is unmistakably her.

The central fact about Dani, the protagonist of Midsommar, on the other hand, is that she desires the commune. What she actually gets instead is, tragicomically, the eugenicist pseudo-commune Hårga, which is a township in Hälsingland—an entirely white Swedish micro-community that her boyfriend’s dreamy friend Pelle, who hails from there, has brought them all to visit.

“What makes both movies so funny and so sad is that, instead of what the women want, it is communitarianism they find, not communism.”

“Dani, do you feel held?” This is Pelle’s question. Long before they fly to Sweden, Pelle, a grad student in the same anthropology department as Dani’s vile boyfriend, has recognized Dani’s desire for the commune by the “strange look in her eyes.” In Hårga, as Dani intuitively (though not uncritically) perceives, no one is an exclusive mother, father, sister, or brother; and every panic attack, fiery death, and even orgasm is heaved, embodied, and screamed, not just by the individual it is “happening to,” but by a whole collectivity gathered around to share in the experience. “Radical reciprocity” is how Aster summarizes this Hårga philosophy. I’ll wager there are millions of us, refugees from the nuclear family, who might feel attracted, called upon, by this crazy vision of affect-communism. I am particularly struck by the spectacle of the Hårga women, post-May-ceremony, holding a collapsed Dani on the floor. They are not just holding her in the way that Christian, Dani’s boyfriend, “held” her in the opening sequence (while she was keening no, no, no, no, no, no, no, no, no): they are really holding her, keening and panting and wailing with her, sharing her affect, and doing so, it seems to me, in such a way as to fold her rage into everything else: her rage is not, I think, expected simply to “burn itself out.”

But Pelle, wooing her in the communal sleeping barn, misjudges her desire radically when he tries to sell her on the totalitarian life of Hårga by saying that what it offers is “real family.” “No, no, that is not what I’m talking about,” replies Dani, in distress. Indeed, earlier in the film the mere mention of the word “family” launches Dani into a panic attack. While she and the handful of other Americans who have travelled to Hårga are blissed-out on mushrooms, one of them announces fakely to the group, “You are like my family,” causing Dani to bolt into the woods and eventually pass out.

What makes both movies so funny and so sad is that, instead of what the women want, it is communitarianism they find; not communism, or even “a room of one’s own,” but—in both cases!—a bio-conservative cult. Still. In Dani’s case at least, it makes her fairly happy. And, for all his faults, Aster, like Tolstoy, is secretly actually quite interested in the production of happiness.

Annie doesn’t want to be a mother, and, in a way, that ought to be okay. Of course, in a world in which there is no alternative to the horrible blackmail of marriage-isolation and private life—especially once you’ve procreated—it is very much not okay. But I have a lot of love for the brutal, bossy, affluent Annie, as played (virtuosically) by Toni Collette. I will say that at various points throughout my adolescence, I was aware, because she told me so, that my mother wished she had not had children. As I write this essay, she is dying, and I love her, and it is my firm conviction that she deserved a world in which that wish—which harmed me so much (while probably harming her more)—need never have arisen.

As for Dani, the agent of what could plausibly be called history’s most epic boyfriend-dumping ever: I may, I warrant you, be somewhat in love. I am smitten with this thoughtful, gorgeous, brave, vital, resilient character, who is played (every bit as virtuosically) by Florence Pugh. I have heard it said, on podcasts I switched off in a huff, that Dani is “as bad as” Christian and that they (somehow, ugh) “deserve one another.” Indignant commentators have agreed—only dimly conscious of their defensiveness—that one thing’s for sure: Christian did not deserve his baleful fate. Like, isn’t Dani at fault, too, when she takes responsibility for his fucking-up? Doesn’t she have a point when she worries how, over their four years together, she may have burdened him too much, pushed him away, by having acute familial pain? Frankly, I’ve never heard such offensive nonsense.

But it should not surprise me, really, that the men of film, the radio-wave wags, don’t want to admit how little they understood Midsommar, and how devastatingly they have been read by it. Here, after all, is part two of a two-part critique that (yes, I realize how unlikely this sounds!) may well be one of the most radically feminist interventions of twenty-first century cinema—and they didn’t see it coming.

I don’t know when I last saw a sequence as beautiful as the marathon maypole dance competition, which Dani accidentally wins because, in despite of being cruelly unsupported by her American companions, and triggered, she is unshakably capable of joy. Shortly beforehand, the reaction of Christian and his friend Josh, a fellow anthropology grad student, to the double cliff-suicide—members of Hårga voluntarily jump to their deaths upon reaching a certain age, a scene which (incidentally) prompted audience members everywhere to walk out of theaters in disgust—is to look at each other, ignoring a dissociating Dani, and puff themselves up, vying for ethnographic “ownership” of the event qua anthropological capital. In contrast, via the maypole scene, we are given to understand that Dani’s response to this same incident is to dance, dance, dance, dance, dance, until she magically starts speaking Swedish (“we don’t need words”). In my view, Aster is doing something very conscious, meaningful, and even brazen here when he places this homage to, as Le Guin might say, the complexity of happiness, hard on the heels of the most darkly shocking scene in the film.

It makes intuitive sense to me that Aster, in order to talk about the contemporary family, works with never-ending dances, queens and princes, houses by the woods, bears, bewitchings, metamorphoses, rites, love spells, and dolls’ houses, in short the stuff of (proto-capitalist, not pre-capitalist) fairytales. Because fairytales, to quote Angel in Daddy Issues again, typically identify “the family as a site of violence—stepmothers poison stepdaughters, children are abandoned or eaten, rapacious fathers violate daughters.” What better way than fairytale symbology to invoke in us our common but deeply repressed knowledge that, for example, it is the family that produces and reproduces the overwhelming majority of the sexual violence on earth?

It also makes complete sense to me that Aster’s excavations of domestic unbearableness are so very, very funny. I don’t just mean the (extremely funny) send-up of credulous Western anthropologists conveyed by, say, Hårga’s use of a bingo machine, complete with lots of wooden balls inscribed with runes, to randomly select its sacrificial victims. I don’t just mean the delicious comedy of the male visitors’ woke-neocolonial subject position in Midsommar; their inability to do psychedelics with any semblance of openness or vulnerability; their near-total passivity even as the cannibals prepare them for the pot. It is, of course, totally delicious that the foul dudes are so busy competing with each other throughout Midsommar and neglecting the traumatized woman they’ve traveled with that they fail to notice that the various objects they are scribbling notes on are literally telling them plainly, over and over again, that they are about to be sewn into a bear carcass and set on fire while she is anointed May Queen.

I also mean the dissociative, sublime humor of Hereditary. It is harder to stomach and harder to admit to oneself, but Hereditary, too, is comic. Take the following marital exchange:

Annie: I just need you to go and see upstairs. Please, Steve. And then … there’s more.

Steve: You mean, more than your mother’s headless body? Of course there is.

Or this, in which Annie is describing almost murdering her daughter Charlie and son Peter:

Annie: I sleepwalk. […] A couple of years ago, I woke up and I was standing next to Peter and Charlie’s bed, when they shared a room. And they were completely covered in paint thinner. And so was I. From head to toe. And I was standing there with a box of matches and an empty can of paint thinner. And I woke myself up striking the match, which also woke Peter up, and he started to scream. And I immediately put the match out. Like, IMMEDIATELY. I mean! I was just as shocked as he was! But it was IMPOSSIBLE to convince them that it was just sleepwalking, which—duh—OF COURSE it was.

Of course it was.

Or this, in which Annie, chatting absurdly fast, appears to think she is describing “her mom’s life” (not her own life) to a stunned bereavement support circle:

Annie: She had DID, which became extreme at the end. And dementia. And … my father died when I was a baby from starvation, because he had psychotic depression and he starved himself, which I’m sure was just as pleasant as it sounds. And then there’s my brother. My older brother had schizophrenia and when he was sixteen he hanged himself in my mother’s bedroom and, of course, the suicide note blamed her, accusing her of putting people inside him. So. That was my mom’s life.

The latter speech, by the way, takes place the day before her daughter’s head gets knocked off in her son’s driving accident, and her husband dies, engulfed in flames, in the living room, before her very eyes. So, when a strange older woman from the support group later runs up to Annie’s car in the parking lot, it is a woefully not-up-to-date version of Annie’s facts she is commiserating with. “My … mother?” repeats Annie, momentarily bewildered. “Oh.” Where to even start.

That aporia, right there, that vertigo: I know what that feels like. Even if the reason it feels funny is dissociation, or the temporary intrusion, in these moments, of something like simple madness, it does, truly, feel funny. I am grateful to Ari Aster for showing me this.

“Midsommar . . . may well be one of the most radically feminist interventions of twenty-first century cinema.”

Hereditary is a film in which family member after family member dies an impossibly gory death until—in a religious ascendance/transcendence sequence that is simply and uncannily joyous—there is only one person left. This “last man,” paradoxically released from his home at last, is the demonically possessed reclusive teenage boy who, in my opinion, is clearly telegraphing to audiences the spectre of the “incel” school shooter. Peter, in this hotly contested ending, becomes “Paimon,” one of the eight kings of hell.

But contrary to the dominant, superficial readings of Hereditary, it isn’t the deaths of his family members per se that fuck Peter up to the point where you feel he might shoot up a school, or preside over a floating headless retinue. It’s their having been alive together in the first place, trapped in the cage of scarcity, atomization, and loneliness. Here’s a mother–son dialogue:

Annie: I don’t wanna say anything. I’ve tried saying—

Peter: Okay, so try again. Release yourself.

Annie: Oh, release you, you mean?

Peter: Yeah, fine, release me.

Here’s another:

Peter: Why are you scared of me?

Annie: [clapping a hand over her mouth, but too late, this slips out:] I never wanted to be your mother.

Peter: Then why did you have me?

Annie: It wasn’t my fault! I tried to stop it.

Peter: How?

Annie: I tried to have a miscarriage.

Peter: How?

Annie: However I could. I did everything they told me not to do, but it didn’t work. I’m happy it didn’t work!

Peter: You tried to kill me.

Annie: No, I love you!

Peter: Why did you try to kill me?

Annie: I didn’t! I was trying to save you!

Ari Aster’s cinema is not, I fear, communist. But Aster is on uniquely intimate terms with a quasi-universal piece of infrastructure that communists will have to unbuild: “a deep well” (as he put it in an interview with Film Comment) “of despair.” The well in question is the Family, functioning normally. Critics and podcasters, for some reason, have consistently missed this, announcing themselves quasi-unanimous in their verdict that Hereditary and Midsommar are “about” grief, trauma, mental illness, personal tragedy, and . . . cults. The violence, so a number of unnerved reviewers have rather conspicuously insisted, is coming from outside the building. The female protagonists definitely love and miss their family members very much. Okay? The spooky or supernatural pagan elements destroying their remaining “relations” are not metaphors for their will, no. It’s easier to believe in demons.

I repeat: I am not saying Aster is a comrade. I doubt he would sign up for family abolition if you asked him, or even give a satisfactory answer as to why abolishing the family is a utopian demand in whose absence the abolition of whiteness and sex/gender becomes unthinkable. However, Hälsingland as presented by Aster nevertheless provides a canny allegory of what happens when the commune is built by white northern ecology: you get bloodline ethno-communitarianism cloaked in tolerance, or, you might say, something like a social-democratic state. This is, after all, a community we observe ritually murdering three nonwhite outsiders over the course of the movie, and two white ones, while using only the white ones for sex and sperm.

On their way to the festivities, the visitors in Midsommar drive past a banner proclaiming a xenophobic policy: “Stoppa massinvandringen till Hälsingland” (Stop mass immigration to Hälsingland). On the other hand, small-scale tourism, if it provides bodies to kill and breed with, is not just okay but actively necessary to the society’s metabolism. The hippie Hårga communards pretend to be groovy and open to all the world, but really, their efforts are single-mindedly channeled into maintaining an image of cyclical, seasonal balance at all costs, preserving the repetition of the seasons and the eugenic stability of their populace just at the moment when climate refugees are presumably lapping at their shores during what they themselves declare is “the hottest summer on record.”

In reality, proto-communist, as opposed to simply communal, life-forms have been the particular province of nonwhite people and other monsters of the white-nationalist imaginary (e.g., rejects and flyaways from the normative household: queers, sluts, race and class traitors, sex workers, and disabled people) throughout colonialism’s history. And, to its credit, by satirizing white indigeneity (sic), Midsommar has enraged some fascists. The editors of the Renegade Tribune, for instance, resent Aster for dragging the good name of Norse spiritual practices through the mud, and have plaintively informed their readership that “New Horror Film ‘Midsommar’ by Subversive Jew Demonizes European Heathens.” Hundreds of jokes about Midsommar being a “documentary about going on holiday with white people,” proof that “white people will go along with literally anything,” or a singular instance of “white people with some actual culture,” have also proliferated rather delightfully on Twitter.

I could not agree more, by the way, that the satanic death-cult in Hereditary is “real.” It’s absolutely real, it’s everywhere. And what Ari Aster is half-consciously demonstrating—indeed, what I am now saying to you in deadly seriousness, fully cognizant that it’s also hilarious—is that, if we persist in reproducing the nuclear family, we are leaving ourselves, as a species, wide open to successful targeting by satanic death-cults. It is because the way that Annie/Dani feel and behave under the influence of a death-cult could plausibly be the way they feel and behave under the influence of a nuclear family, that we have to abolish the family.