New York is sending HQ2 back with one-day shipping.

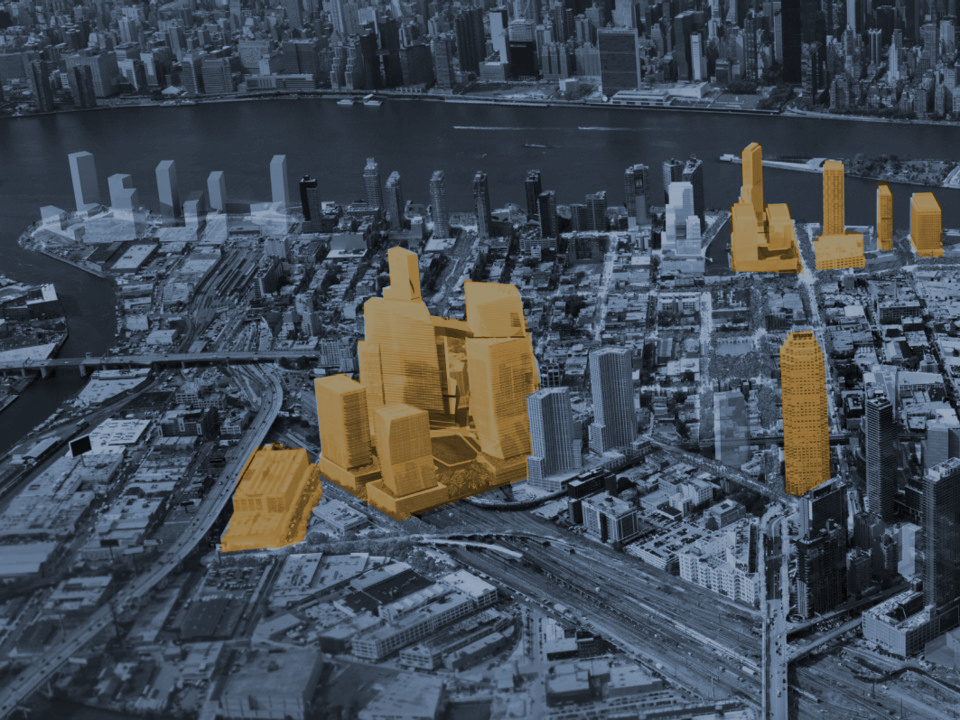

I’m standing on a lonely, dog-shit-covered pier at the western tip of Long Island, the winter wind eating through my denim jacket. Before me lies Roosevelt Island, once home to New York’s hospitals, prisons, and asylums, now full of luxury apartments and a Cornell University “tech campus” meant to drain money and talent from Silicon Valley. Beyond that is Manhattan’s east side—United Nations headquarters, the gaudy Trump World Tower, and the subdued money behind the bricks of tony Sutton Place. To the north rises the steel hulk of the Queensboro Bridge, which ferries 170,000 automobiles a day between Manhattan and its sister to the east, while behind me sit a shuttered restaurant, a rotting wooden pier, and a series of brick warehouses. This site, hard by the shore of the East River, was to be the footprint for Amazon’s “HQ2,” where tens of thousands were supposed to toil for the world’s most aggressive retailer. But now the deal is dead, cut down by a swell of opposition from neighborhood activists and elected officials that caught the company and its supporters flat-footed.

Amazon’s retreat is significant. Subsidies to private firms are not new, but HQ2 was the moonshine of development deals—strong, pure, and harsh. For many New Yorkers, the deal became a symbol of everything they find objectionable about contemporary urban politics. Amazon’s market valuation exceeds a trillion dollars; its founder, Jeff Bezos, is the world’s richest man. Nonetheless, city and state officials offered the firm at least three billion dollars in subsidies on the heels of a year-long search process that doubled as a humiliating showcase for the sovereignty of private wealth over desperate municipal governments. The deal, shrouded in secrecy and engineered to abrogate whatever democracy remains in New York’s planning process, stood as a monument to the contempt with which both corporate and elected officials treat ordinary people in any role except that of customer.

Long Island City

During the last ten years, Long Island City has changed as much as any place in New York. Real estate developers have converted large swaths of industrial waterfront into glass-fronted playgrounds for today’s rich. At midcentury, Long Island City sat at the center of a vast belt of industry folded around the western fringe of Long Island. The intensity of this landscape drove the scribes of the Federal Writers’ Project to rhapsody:

Long Island City, fronting the East River and Newtown Creek around the approach to the Queensboro Bridge, is a labyrinth of industrial plants whose harsh and grimy outlines rise against the soot-laden sky. Within an area of a few square miles, gridironed by elevated lines, railroad yards, and bridge approaches, are gathered about 1,400 factories, producing chiefly spaghetti, candy, sugar, bread, machinery, paint, shoes, cut stone, and furniture. Its bakeries alone turn out about five million loaves weekly; its paint and varnish factories, about ten million gallons a year; its stoneyards handle about 90 percent of the cut stone and marble imported into the United States. On the oily waters of Newtown Creek, which separates Queens from Brooklyn, tugboats and barges plow busily all day long, entering with coal and raw materials and leaving with manufactured products.

Food and chemicals were the neighborhood’s mainstays. When La Guardia Community College opened in 1971, the neighborhood smelled like “bread and gum,” recall teachers. When the Chiclets factory exploded in 1976, workers poured out of the plant “still smoldering,” reminding a shaken witness of photographs depicting Vietnamese children attacked with napalm. In retrospect, the blast feels like the coda to an era, an angry outburst by machines protesting their impending retirement. By the 1980s, the deindustrialization of New York was virtually complete, leaving the city hooked on finance and real estate as motors of the local economy. While its Rust Belt counterparts descended into penury, New York parlayed its historical advantages into a new season of opulence, riding high on asset bubbles and debt-gorged turbulence administered from its downtown boardrooms. New York may be built on quicksand, but at least it is built on something.

“Competition suffuses every inch of Amazon’s soul.”

Other historical legacies abound in Long Island City. The Queensbridge Houses, the largest public housing project in the United States, sit five blocks north of the HQ2 site. Completed in 1939, the twenty-nine squat brick structures evoke an abandoned American social democracy. Today, while luxury towers rise to the south, the New York City Housing Authority lurches from crisis to crisis. Eighty percent of public housing residents went without heat some time last winter. Some have lived like this for ten years. Lead paint, piles of trash, dirty water, no water—an archipelago of Flint, Michigans stretches across each New York borough.

Between the 1960s and the 1980s, the Queensbridge Houses, like other New York public housing complexes, became sites of concentrated, racialized poverty, the consequence of a slowing economy, labor markets cleaved along racial lines, and state policies that fostered segregation. More than most projects, though, the Queensbridge Houses spoke to the world. The compound is famous for its poets. In the 1980s, MC Shan, Marley Marl, Roxanne Shante, and the Juice Crew helped set the template for New York hip-hop. Their ‘90s descendants—Nas, Cormega, Tragedy Khadafi, and others—honed the style into something harsher, less playful, more world-weary.

Perhaps more than any other Queensbridge rappers, the duo Mobb Deep spoke for those who, by virtue of their race and class, had to live the cardinal values of neoliberalism before the rest of us. Coming of age in the midst of a racialized employment crisis and the death of an intra-project informal economy, no group so obsessively channeled the insecurity borne of universalized competition, the war of all against all. Prodigy spoke of human beings as meat—lifeless prey, instrumentalized for the temporary survival of others. The world of Queensbridge amounted to “forever beef—nobody will ever be even.” Over ghostly fragments of the music of their parents’ generation, Prodigy and Havoc composed a kind of oral history of the psychic consequences of wageless life—of absolute proletarianization. If poetry is speech that isolates, dramatizes, and intensifies, then Mobb Deep were poets of the death, literal and figurative, that suffused working-class black New York at the height of the unemployment, drug, and AIDS crises of the 1980s and 1990s.

The hustle—a life of eternal vigilance, of ceaseless activity—responds to this insecurity. Alongside their paeans to street life, Mobb Deep communicated a deep ambivalence about its consequences, a recognition that possessive individualism can never be a solution for oppressed people whose structural role in the economy is to have nothing. HQ2, which would have put Queensbridge survivors nose-to-nose with six-figure transplants, would have marked New York’s embrace of a firm whose success is consequence, cause, and symbol of the way this insecurity has generalized in the United States. Amazon, the world’s most anti-social firm, sits at the leading edge of a society run on extortion, isolation, and antagonism.

Competition suffuses every inch of Amazon’s soul. The company, an engorged behemoth, fed on a bitter cocktail of Taylorism, tax avoidance, and monopoly power, long boasted of its cruel work culture. The firm’s “burn-and-churn” personnel strategy is well-known in Seattle, where fellow tech workers shun “Am-holes” for their anti-social disposition. Warehouse workers, poorer and darker, are monitored in terrifyingly granular fashion, driven to sickness and injury, afraid to use the bathroom lest they miss their quotas. Few last longer than six months. “If I had to characterize it in a word, it would be fear,” reported a journalist who went undercover in a UK warehouse.

Many things about Amazon are new, but some are not. A hundred years ago, Frederick Winslow Taylor pioneered the use of time studies to wring more effort out of laborers at the Midvale Steel Works. Taylor knew that when you measure effort, you create a peg of accountability, an autonomous power, a whip. The rule of the economy is the rule of numbers—of human experience abstracted, quantified, and fashioned into a weapon to be used against us. Its purpose is to extract—to appropriate our creativity, our physical prowess, our abilities, and direct them in service of a power that is not ours. Amazon, observes a former employee, is a “time-thief.” It steals time and effort and turns them into prices that keep consumers furnished in an era of stagnant wages and skyrocketing debt.

When he announced the deal in November, New York mayor Bill de Blasio crowed about the juxtaposition of “one of the biggest companies on earth next to the biggest public housing development in the United States.” “The synergy is going to be extraordinary,” he asserted. Given the conditions in New York public housing, the skyrocketing homelessness, the state of the subways and buses, and the role of real estate development in fostering the most grotesque inequalities, these comments struck many as obscene. And they were, if only because they crystallized so succinctly the core of de Blasio’s unworkable politics.

In the future, we will look back on de Blasio’s mayoralty as a case study in what can be achieved as a left wing of neoliberal urbanism. Following the era of deindustrialization, capped by the city’s legendary fiscal crisis, every New York mayor has fixated on increasing real estate values as the sine qua non of urban politics. De Blasio vaulted to the mayoralty on the basis of his promise to “guard the people from the enormous power of moneyed interests.” During his five years in office, the mayor’s rhetoric has shifted from a “tale of two cities,” with its rhetorical gesture toward class conflict, to an ostensible program to create “the fairest big city in America” through class compromise. In de Blasio’s world, you can have runaway real estate development and the foundations of a dignified life for those without money. Indeed, the latter depends on the former. This is the “have it all” delusion at the center of neoliberal social democracy.

The margin of error for this strategy is thin, its results meager. Its first principle is to concede that we live off the scraps of the real players, that our ability to care for ourselves depends on fostering the very things we hate. This immobility explains why de Blasio must plump for a company whose ethos violates everything he claims to stand for. This is the “synergy” he seeks to engineer. By these lights, the mayor isn’t a hypocrite, but he is a failure.

“I Blame the Landlords”

When the deal was announced late last year, I took the subway out to Long Island City to poke around the proposed site. Unprepared for the wind slicing in off the river, I ducked into Brooks 1890, one of the oldest continuously operated restaurants in the city. The place was nearly empty. Two seats down, an elderly patron, nursing a Bloody Mary, chatted with the bartender. The subject was—what else?—real estate. In New York, the belligerence with which investors have torn away a long-settled urban fabric forms a kind of conversational default, the way I imagine sports might in other places.

“New York’s dead,” pronounces the bartender. “I blame the landlords.” He invokes a natural disaster. “You can’t stop the wave,” he shrugs. He’s right, I think to myself. For so long, capital—nameless, depersonalized, omnipotent—has appeared to us like an unmoved mover, a god. It suddenly occurs to me I have never laid eyes on the people who own the building in which I spend my most intimate moments.

But now, two months later, a major corporate subsidy deal has collapsed under organized popular pressure. Real estate capital and its political allies have been dealt a stinging defeat. It’s not the revolution, but it is a clear shift in direction.

“Amazon, observes a former employee, is a ‘time-thief.'”

How was HQ2 defeated? A basic answer is that elected officials, feeling the heat of popular pressure, declined to rally to the company’s side and in some cases openly antagonized the firm. When State Senator Michael Gianaris, an outspoken critic whose district includes Long Island City, was nominated to a state board with veto power over parts of the arrangement, it was a signal that Governor Andrew Cuomo might not be able to deliver the rubber stamp Amazon had expected.

Gianaris, along with Long Island City’s City Council representative, Jimmy Van Bramer, signed a letter in 2017 urging Amazon to come to New York. A year later, the two emerged as some of the most vocal critics of the deal. What changed? During that time, New York witnessed a series of earthquakes in the normally opaque realm of electoral politics. Last June, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez expelled establishment Democrat Joseph Crowley from his congressional seat. In September, primary challengers dispatched most of the conservative Independent Democratic Conference. And Julia Salazar, with the backing of the Democratic Socialists of America, ousted pro-real estate Democrat Martin Dilan in a district that had shed 20 percent of its rent-regulated housing on his watch. It is no longer feasible for Democrats in New York City to serve the real estate industry and expect to remain unchallenged. Popular pressure, expressed in primary challenges, is forging a new common sense among elected officials who now find it in their self-interest not to ignore working-class demands.

At the same time, a grassroots movement composed of unions, anti-gentrification activists, anti-poverty groups, radicals of varying shades, and everyday New Yorkers, formed and began to pick up steam. The movement launched an intensive canvassing campaign and offered a show of force at City Council hearings during which startled Amazon representatives weathered hostility from both the podium and the gallery. This seemed to portend a long and increasingly disruptive struggle. In this new climate, Amazon realized it could not locate in New York without enduring intense, ongoing public scrutiny of its labor practices, its role in displacing working-class residents, its relationship with the US border-security regime, and the painful, alienating society it fosters and represents.

The significance of this popular pressure cannot be overstated. Without it, Amazon would have sailed through ostensible checks on its power in the manner of countless development deals of yore. The power of the wealthy rests on the resignation of the poor. This resignation—the conviction that there is no alternative—was actively encouraged by the governor and mayor. Amazon, it is clear, was counting on it. The company, so accustomed to crushing politics with money, was unprepared for an opposition that could organize beyond the inchoate grumbling that has so often marked the limits of popular politics in our lopsided times.

The defeat of HQ2 points to an ongoing shift in city politics away from neoliberal urbanism and towards the municipal social democracy that once defined New York. The push to broaden and strengthen rent controls is another sign of this trend. Social democracy in one city has limits. The old municipal social democracy ran aground on its geographical isolation and inability to transcend the basic rules of capitalism. Already, the credit ratings agencies, the closest thing we have to an executive committee of the bourgeoisie, have threatened the city for its betrayal. Partisans of the HQ2 deal repeatedly invoke the city’s 1970s fiscal crisis, hoping to batter opponents with the spectre of capital flight.

These risks are real, but for now they lie in the future. The immediate task is to deepen the critique beyond Amazon, to broaden resistance to the rule of real estate in general. Having defeated the spectacle, we must attack the substance. Amazon, whose arrogant detachment piqued moderates and radicals alike, proved an exceptionally ham-fisted adversary. The chastened firm now has an opportunity to expand into New York in the manner of its more politically sensitive compatriots. The defeat of HQ2 bears little on the company’s outposts of misery in Staten Island and the Bronx, unless warehouse workers can translate public opprobrium into a successful unionization drive.

The lesson, for now, is that a recalcitrant left pole is necessary in order to hold the powerful accountable in the here and now, to extend critiques beyond the particular, and to propose concrete measures we think can loosen us from the dictatorship of the market. “We cannot negotiate our lives, our homes, our families,” explained Sarah Gee, an organizer with the Fuck Off Amazon coalition, which distinguished itself from some HQ2 opponents by its unqualified rejection of the company.

This is not simply a moral position. We are talking about confronting the deep structure of the economy, the sedimented power of entrenched wealth. In a contest with such forces, premature compromise is death. For this reason, we need partisans of intransigence who can draw clear lines. We need people who can point out that in a scarcity economy governed by blackmail, there are winners and losers. We need people who can connect the dots, who can show us that it’s not that they have things and we don’t—it’s that they have things because we don’t. The defeat of HQ2 is significant because it transcends arguments about the hypothetical benefits of this or that compromise. In their place, it has established the rejection of extortion by the wealthy as a basic principle. We must insist that there is no going back.