Nick Estes tells us why the past and present of Indigenous resistance means there must be no future for the United States.

JC: Your book, Our History Is the Future, begins from one of the signal social movements of our present, the Indigenous encampment at Standing Rock, comprising a number of separate camps. It is at once the coming together of the Oceti Sakowin nation, a legitimate challenge to powers of capital and state crystallized in the Dakota Access Pipeline, and a moment of expansion where indigenous struggles are joined — literally, physically — by others flowing in from elsewhere. All of which is to say, it is a dramatic moment of political confrontation. Your book does not simply situate itself in the descriptive thrill of this one moment for a couple hundred pages. It really wants to know what it means, how it arose, what it could become. Even the simple question of how or where the event called “Standing Rock” started proves elusive; inevitably, even if we are just looking at Indigenous tactics, we will end up looking at Keystone XL and Idle No More, but that will take us back to the Oka Crisis and Wounded Knee . . . We get carried back swiftly by the current of history: from the earliest contact of European settlers with the Indigenous people of what will be called North America, to the war the settlers will wage on Indigenous life both militarily and through the brutality of statecraft, through fights over treaties, sovereignty, recognition, and more. One of the things this achieves for me, in addition to the extraodinary historical thickness, is something like a demand to see not just how history is “one single catastrophe” but to see it from within an Indigenous worldview. But that is just a start. Tell me about how you chose that strategy of storytelling, theorizing, knowledge-making — how it came to you, and what you want it do?

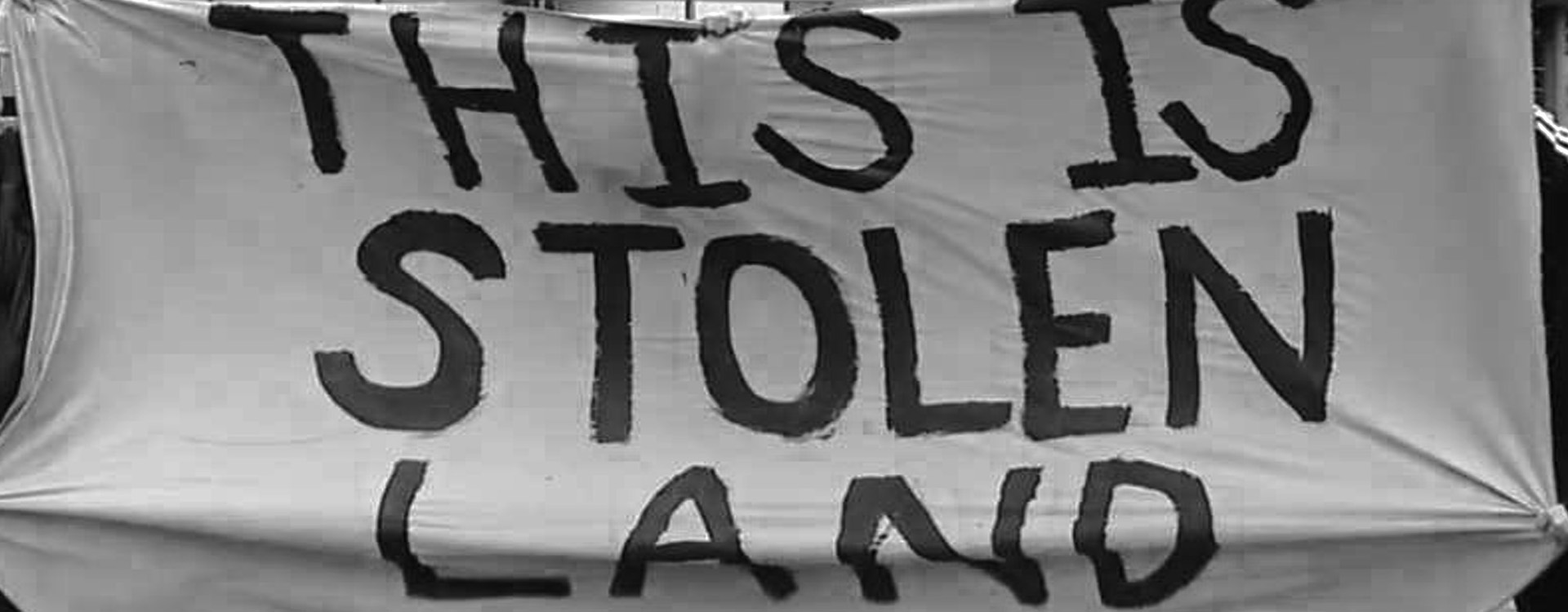

NE: Standing Rock is an entry point for telling the history of the Oceti Sakowin. That is my primary goal. My other hope is to provincialize US history — not so much the history of the United States but the settler narratives. Therefore, it’s not merely a history of US settler colonialism, but it is more so a history of Indigenous resistance. The subtitle of the book, after all, is the “Long Tradition of Indigenous Resistance.” While I didn’t theorize it much in the book, I try to elaborate an Indigenous revolutionary and anti-colonial tradition by locating it in a long arc of history rather than selecting one moment of uprising as exceptional. Here I take my cues from thinkers such as Cedric Robinson, Robin D. G. Kelley, and Ruthie Gilmore, who theorize and document the Black Radical Tradition. While distinct in important ways, there are parallels and commonalities with traditions of Indigenous resistance.

The best way to explain it from a Lakota perspective is to give an example. During a Q&A session in Albuquerque for Warrior Women, a film about women in the Red Power movement, a Diné student asked Madonna Thunder Hawk, a Lakota leader of the American Indian Movement (AIM), why she had sacrificed so much to be part of the struggle, why she gave up the normative aspirations of motherhood and family life. “I want to be remembered as a good ancestor to future generations,” Madonna answered. A Dakota intellectual, Elizabeth Cook-Lynn once put it this way to me, “You don’t even own your life, my dear. You’re simply here to ensure the coming of the next generation.” I don’t think this equates to stoicism or fatalism. It’s incredibly meaningful to step foot into the stream of our history, to know that you are part of a web of relations with the past, present, and future, with a solid (but not immutable) foundation that can be grasped rather than trying to build something entirely new every generation.

Traditions of Indigenous resistance, as I understand them, are part of what Raymond Williams once called a selective tradition. A selective tradition chooses prior experiences of one’s ancestors as forebears (and sometimes invokes them as active participants — such as AIM’s popular phrase, “In the spirit of Crazy Horse!”) to inform current resistance movements, while sustaining them as part of a living tradition in constant formation. In this sense, traditions of Indigenous resistance are not entirely new, nor are they necessarily a checklist of people or concepts. Traditions of Indigenous resistance are an accumulation of ways of knowing, experiencing, and practicing relationality to humans and nonhumans, a radical consciousness, deeply embedded in history and place, that expresses the ultimate desire for freedom and liberation.

If understood this way, Standing Rock is still important but less exceptional, which is a good thing. It was simultaneously a movement within a moment in time as well as a moment within a longer movement of history. We concede too much when we allow imperialism to tell our stories. For example, with the ’80s and ’90s nostalgia in popular culture, everything old is new again. We’re made to forget the halcyon days of violent, right-wing counterrevolution under Reagan and Bush and the inauguration of neoliberalism. Because of this mass societal amnesia, it’s not intuitive to see oneself as part of a longer tradition.

That’s why I wrote the book the way I did: to inspire confidence in young Native people, first, and other allied struggles, second. Would you rather fight this system as an individual? Or with a thousand ancestors at your back and in front of you? We have a solid foundation that even mass genocide couldn’t destroy, so let’s use it.

JC: The great antagonism in the book is between the United States and Indigenous peoples, or more abstractly between the settler state and indigeneity itself. Along the way you touch on some rifts, or at least strategic debates, within the Indigenous political vision, for example in orientation toward the militancy of AIM in the seventies. I always want to know about these moments because they are both necessary, and a way of posing the problem of what must be overcome for this social movement to take on greater power. So I’m curious to understand what rifts or debates were present within the Standing Rock encampment — among the various camps or tendencies or participants — regarding how best to achieve the movement’s goals, most immediately that of stopping the pipeline?

NE: The strategy of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe was, from the start, to use the camps and the non-violent protests to pressure politicians and courts to take action in their favor and reroute the pipeline. This worked in tandem with hard and soft actions, such as lockdowns of construction equipment and frequent prayer marches and picketing. We now know that police and private security from the beginning aimed to widen divisions within the camps. As police violence increased, so too did the rifts among different tactical orientations. (That’s also not to say that those divisions didn’t exist before.) But it is clear that they were actively exploited and purposefully pitted against each other in media reports.

Police admitted as much following the eviction of the camps. Cass County Sheriff Paul Laney, who worked the protests, put it bluntly: “We’re literally fighting a war.” He was speaking at a National Sheriff’s Association webinar to other law enforcement for a recounting of “lessons learned” on how to wage an “information war.” One of the corporate sponsors for the event was TigerSwan, the private security company that cut its teeth in the US War on Terror in Afghanistan, and who also provided intelligence briefings to law enforcement policing the Standing Rock protests.

Your question was about rifts and debates among the tendencies and camps of Water Protectors. Before we can honestly talk about those divisions, we have to have a genuine conversation about state repression, which plays a heavy hand in crushing any challenge to the colonial state. The tactics are as old as invasion itself.

At first, all the camps in both Sacred Stone and Oceti Sakowin took direction from Standing Rock. But that relationship began to sour as police violence intensified. The camps were, for the most part, “family friendly,” and not everyone was a frontline warrior. There were safety concerns from the beginning.

The overall strategy of the camps was, in this order: stop the pipeline, unite the Oceti Sakowin, and unite with allied movements for climate justice. The camp was a tactic, part of a long-term strategy to accomplish those goals, at least in the beginning.

So when Standing Rock asked the camps to leave after December 5, it created a rift. One side argued that this fight was more than Standing Rock, and the camps themselves weren’t on treaty land so not Standing Rock’s problem. This group favored continued direct actions. The tribe argued that the fight was in the courts and out of the hands of the people. And they began working more and more with state agencies like the Army Corps and police to negotiate an end to the protests. The two tactics, direct action and political pressure, which had previously been complimentary, were now pitted against each other. That’s when the police repression stepped up, because it was vindicated by a “good Indians” versus “bad Indians” media narrative that even some of the Water Protectors and tribal leaders themselves repeated.

If there’s a lesson that I want to impart, it’s that cops and colonizers are not your friends; don’t let invaders splinter your movement; and take seriously the capacity of state forces to crush your struggle. The only way to overcome these obstacles is committed organization.

JC: The second chapter, “Origins,” begins: “There is one essential reason why Indigenous people resist, refuse, and contest US rule: land.” This seems inarguable to me. It also summons a series of longstanding problems or, dare I say it, problematics, regarding analytic frameworks for struggle. One convention, that floats through a wing of postcolonial studies (but can also be found, for example, in Malcolm’s “Message to the Grassroots,” when he writes, “It’s based on land. A revolutionary wants land so he can set up his own nation, an independent nation. . .”) is to make a strong distinction or even opposition between struggles over land and struggles over labor exploitation, associated with settler colonialism and with capitalism respectively. I don’t expect you to untangle this in a few hundred words, but can you maybe outline your thinking on these matters?

NE: When the organizing principle of a settler society is Indigenous erasure, it infects all levels. You can’t have capitalism in the United States without settler colonialism and white supremacy. Likewise, if your anti-capitalism isn’t also anti-colonial, and if your communism isn’t also advocating decolonization, then what are we really doing? Labor and land struggles don’t have to be competing movements for change, though people with no real power are often pitted against each other. If we can unite them, that’s when this system will really begin to crack.

JC: The question of ecological crisis cannot be separated from matters of indigeneity and the status of nation and border. I am particularly interested in the Red Deal, whose core principles were developed at the Red Deal coalition gathering in 2019. The name, at least, chimes with the much-debated Green New Deal. We at Commune are largely skeptical of policy-based solutions to climate collapse, and I think there are very good reasons to be militantly opposed to a state-based “Green Nationalism.” One core difference of the Red Deal is that it arises from a long and profound tradition of kinship relation with the land. Could you emphasize some other ways that the Red Deal breaks with the Green New Deal vision of transformation by policy and electoral success?

NE: No one in the settler state is seriously advocating land return to Indigenous people. You’ll never hear even the most progressive politicians say something like, “We need to repeal the Homestead Act of 1862, which stripped 270 million acres of land from Indigenous people.” The state-centered approaches require either maintaining or facilitating continued land dispossession and levels of consumption that are simply unsustainable. Most approaches are reformist in nature, meaning they advocate incremental change or the further normalization of settler colonialism.

After the period of violent, and sometimes genocidal, counterrevolution that birthed neoliberalism, socialism and liberation were no longer seen as winnable. The capitalist-colonial state, then, becomes the horizon of struggle. This is our current moment. The Red Deal is a challenge to these limited aspirations. Our strength as Indigenous peoples is that we make relations with human and nonhuman worlds — to turn outsiders into familiars in order to relate, as Kim Tallbear put its. Why would you want to make relations with a white-supremacist empire? On principle, The Red Nation makes relation with allied struggles from below. The Red Deal is a deal with the humble people of the earth and with the land itself, not the rich and powerful.

There are economic and political alternatives that can be built and strengthened. We call them caretaking economies, in which land-based economies in rural and urban spaces center correct relations with each other and the earth. This is the antithesis to the caretakers of violence such as the police and military.

JC: The Red Nation seems like an ambitious and compelling extension of what we might call the spirit of Standing Rock into an ongoing collective political project. I wonder if I could first ask you just to talk about its origins, what it is, how it means to function?

NE: The Red Nation formed in November 2014 in the aftermath of the anti-police violence movement that surged in Albuquerque. That summer, three young men brutally beat three Navajo men, killing two of them. The slayings were part of a long-standing practice of “Indian rolling” or “Indian busting,” where settlers attack or sometimes kill Native people on the streets for sport or fun. This kind of violence upholds the “common sense” (in the Gramscian use of the term, meaning cemented, hegemonic bourgeois norms) that Native people need to “go back to the reservation,” solidifying the notion that the cities and white settlements are not Indigenous spaces. We call that “anti-Indian common sense.”

The American Indian Movement formed to end the police violence against Natives as well as vigilante attacks common in reservation border towns, the white-dominated settlements that ring Indian reservations. And we were greatly inspired by the Black Panther Party’s Ten-Point Program.

We started as a coalition and quickly evolved into a full-fledged membership organization. There are now what we call “Freedom Councils” in Gallup, Albuquerque, and Santa Fe, with more springing up in the Bay Area, New York City, and South Dakota, and an at-large membership around the country. While focused on Native liberation, we’re open to folks who don’t identify as Indigenous. And from the beginning we’ve adopted and practiced socialist and left principles of organization. We’re also explicitly queer and feminist in our orientation towards political struggle. Since we come from different nations, we’re also multinational and internationalist in our outlook.

Our overall goal, again in a Gramscian framing, is to develop the anti-colonial common sense many Native people harbor and turn it into a good sense, which transforms an experience of injury into an organized revolutionary movement. We aim to function as a left pole in the Indigenous movement, operating autonomously and democratically entirely outside the nonprofit industrial complex. We aim to provide an alternative not only to Indigenous organizing but to the system itself. And many of us see those solutions as firmly rooted in our traditions, cultures, and nations. As we say in our “Principles of Unity,” “we are the ancestors from the before and the before and the already forthcoming.”

JC: The Red Nation statement “Revolutionary Socialism Is the Primary Political Ideology of The Red Nation” takes the side of both socialism and communism. For me, the relation of these is the historical-political question, alongside climate catastrophe. The longstanding Western convention is that socialism is a transitional mode through which state and production are seized by the people, eventually giving way to a society lacking both a conventional state and capitalist production altogether. That image of transition has lost much of its charisma, in part because of the failings of the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China, in part because the workers’ movement on which it was originally premised no longer exists. Certainly one strand of contemporary democratic socialism seems to hold that communism is no longer on offer. Can you offer your own sense of how The Red Nation thinks about the relation between socialism and communism?

NE: Our position on revolutionary socialism, like everything we do, is as much an elaboration of our collective politics as it is a document that exists in relation to all we’ve done. It doesn’t exist in isolation from, for example, our positions on Palestine and queer Indigenous feminism. Like many on the left, we’re in a period of debate and political development, specifically around the question of the state. I can say with confidence we don’t think there is a future for the United States, as we know it, or settler colonialism, if there’s going to be a future for Indigenous people and life on this planet.

We do agree that it is irresponsible to turn away from the state as a site of struggle when so many of our relatives and comrades are caught in the maw of the system, whether by police, prisons, la migra, or child protective services. We can’t imagine those institutions away, especially when they’re so fundamental to maintaining the accumulation of capital by driving down wages and seizing and commodifying nature. The state has to be confronted and challenged at all turns.

We see socialism as the transition towards communism. Just as capitalism took centuries to establish itself, we know socialism won’t happen overnight. It has already been a long, bloody process with significant victories and defeats. Communism is the idea that history hasn’t ended but must continue.

JC: Last things you want to say? Favorite song of 2019?

NE: Noura Erakat posted a video of 47Soul on social media. And I can’t stop listening to the song “Machina” from the album Balfron Promise. It’s music clearly inspired by the Great March of Return, which lights my fire.