No one is disposable.

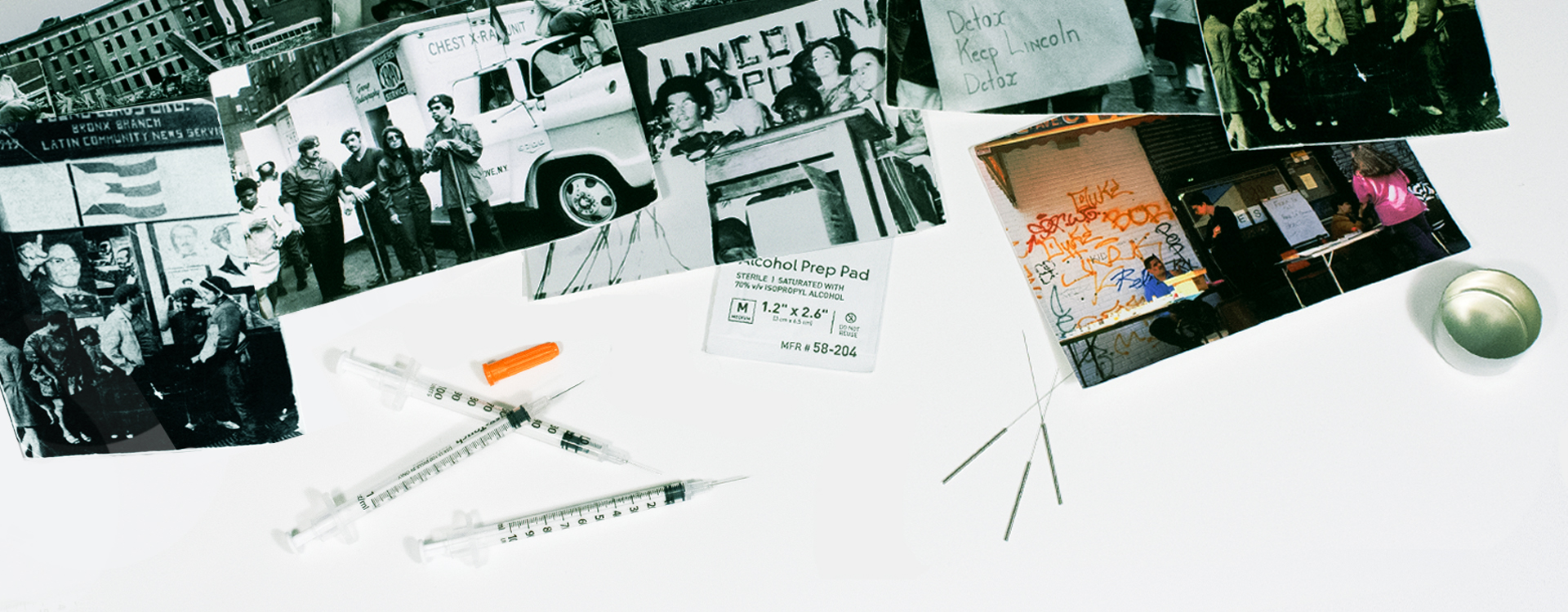

In November of 1970, the Young Lords and the Black Panther Party seized a section of Lincoln Hospital, establishing the first drug detox program in the South Bronx, the center of the city’s heroin epidemic. The “People’s Detox” operated out of the old nurses’ residence under a coalition of Black and Puerto Rican left nationalists, socialists, and radical medical workers. Influenced by the psychological work of Frantz Fanon, they saw revolutionary political education as essential for overcoming drug addiction. Mutulu Shakur, Vicente “Panama” Alba, Cleo Silvers, Dr. Richard Taft, and others who ran the program innovated the use of acupuncture as a drug treatment modality in the US, a practice that has since become institutionalized and widespread. They won city funding for the detox program in 1971. They continued to run it until the police raided the detox facility in 1978, expelling the revolutionary leadership. These years were peak periods of political organizing for the Bronx, as well as the years that HIV — still unnamed and unnoticed by medical authorities — first started to claim the lives of injection drug users.

The Lincoln Hospital Offensive, as the Young Lords called it, was one of their several health-related campaigns. The Young Lords held a sit-in at a health commissioner’s office demanding lead paint screening for children in East Harlem and the South Bronx, and hijacked a mobile X-ray truck to screen for tuberculosis. In this way, they anticipated the coming decades of crack addiction, the epidemic of HIV and AIDS, and the rapid growth of mass incarceration. They were also recognizing a limit to their own organizing, as drug addiction contributed to the unraveling of the revolutionary organizing and mass insurgency of the early 1970s.

These initiatives took place in the context of a broader movement to improve, democratize, and seize the considerable social democratic infrastructure New York City had built after WWII. Black women in the welfare rights movement staged sit-ins to gain welfare benefits. Black and Puerto Rican labor activists successfully organized to expand hiring for unionized municipal government jobs. Students occupied buildings of the city’s free public university system, winning “open enrollment.” These militants confronted the racial contradictions of New York, seeking to transform a labor-backed social democracy to serve and be subject to the city’s growing Black and brown working class.

By focusing the Lincoln Hospital Offensive on establishing the Bronx’s first detox program, the Young Lords and their allies staked a position on one of the most contentious questions of twentieth-century socialism: the political role of those members of the working class who are rarely able to hold down a job. The mass socialist parties of Europe, seeking a politics of working-class respectability, had long been ambivalent towards the “lumpenproletariat,” “the underclass,” “the poor.” If the dignity of work is the basis of socialism, junkies unable to maintain stable employment have no place in the revolutionary project. By turns seeking the moralistic redemption of the poor by absorbing them into the working class proper or excluding them from the socialist imagination altogether, the workers’ movement saw the poor as those outside their constituency. In the US, the lumpen were unambiguously racialized, associated with the Black and brown youth who rioted in over 150 cities during the late 1960s.

“If the dignity of work is the basis of socialism, junkies unable to maintain stable employment have no place in the revolutionary project.”

Drug dealers and drug users embodied the qualities of the lumpen masses that socialists had long scorned: unreliable, undisciplined, easily vulnerable to the pressures police put on them to rat out their comrades. Inspired by the Black Panthers, the Young Lords broke with this socialist orthodoxy, instead basing their organizing on recruiting the young men of color hustling on the streets of urban America. The Young Lords understood that the chaos of drug addiction was wreaking havoc on working-class life, and sought a way of transforming addicts into revolutionary subjects.

These struggles of the criminalized and racialized poor were particularly potent because they were not severed from the broader working-class insurgency of the time. The Black workers leading a wave of strikes in auto manufacturing, healthcare, and municipal jobs broadly sympathized and overlapped with those joining the riots of the late 1960s. The Health Revolutionary Union Movement (HRUM), the militant medical-workers group that joined the Young Lords at the Lincoln occupation, took their inspiration from the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement (DRUM), an organization of Black workers in Detroit’s auto plants. Within Black and Puerto Rican movements of the time, different sectors of the working class built real relationships of solidarity and struggle.

The Young Lords’ organizing with drug users recognized an essential feature of the communist endeavor: the miseries of life under capitalism fracture the working class, breaking people’s bodies, and disposing of our lives. Overcoming class society will require a practice of healing, a reclamation of the universal dignity of human life, and a means of building solidarity and love across these fractures within the working class. Nowhere is this understanding more crucial or more difficult than with those trapped in severe and chaotic drug addiction.

_____

I learned about the militant origins of the Lincoln Hospital Detox Program shortly after I moved to East Harlem to work at a syringe exchange program based in the South Bronx. Early each morning we would load a van and a utility truck full of empty sharps containers and boxes filled with sterile

medical syringes. We would follow the traffic onto the Bruckner Expressway to that morning’s exchange site. My coworker Angel would take the lead, setting up tents and tables and stacking our supplies. On especially cold days, we would fire up gasoline-powered heaters. A couple of the staff would take seats at the exchange table, and begin chatting with the steady stream of participants who came through. Isaiah, an African-American man in his early seventies, would staff the acupuncture tent. The exchange’s best-dressed employee, with his colored suits and fedora, Isaiah provided stress-relieving, ear-based acupuncture in chairs set up on the sidewalk alongside our exchange.

I’d begin my shifts moving boxes around, making coffee for the syringe-table workers, then chatting with my coworker Ricky. Originally from Puerto Rico, Ricky had spent the 1970s and 1980s dealing heroin in the Bronx to keep up his own steady use. He remembered the early hip-hop parties organized by Kool Herc at the Bronx River Houses. He eventually got clean and has been employed at syringe exchanges ever since. Most of our coworkers were former users, but we knew a few still shot up regularly. I would talk to Ricky about books. I was reading on New York City history, the Young Lords, or the city government leaving the Bronx to burn. He would tell me about growing up in the projects, the time he spent in and out of jail, and occasionally crossing paths with the revolutionary parties and nationalist sects that competed for new recruits in the Bronx.

The participants in our program — we called people who came for syringes and services “participants” rather than the more hierarchical and institutional-sounding “clients” or “patients” — came for clean syringes because they cared about their lives and the lives of those they used with. They shared a common experience of using injectable drugs, mostly heroin, and enough difficulties in their lives that they couldn’t arrange to order their syringes discreetly online. Most had spent years homeless or passing in and out of jail. Many grew up in the Bronx, while others had recently moved from the Caribbean. Many trans women came by the exchange for syringes. Like many women who came to our exchange, they had spent time getting by through sex work.

Two or three times a day, a participant would ask about getting into a detox program. I would set aside the flyers I was handing out, and we’d sit in the back of a utility truck together and talk through options. My job was to find people a bed in a detox facility somewhere in the city, and to arrange the transportation to get them there. Detox programs were designed as a first step in a long process of getting clean after many years of severe addiction. Occasionally participants I’d work with would aspire to stay clean, but for many others detoxes were instead the means of getting off the street for a few days, getting away from the stresses of chaotic home lives, or avoiding a demanding creditor or angry dealer. Detox programs would provide enough medication to take the edge off of drug withdrawal, and detox could be a way of resetting and pulling oneself together. Many participants lacked any form of identification after periods of homelessness. I would help them track down offices where they had previously received medical care, hoping a photocopy of some ID was still on file. I would help untangle people’s Medicaid; after repeated detox visits their government-provided insurance would be restricted to a single facility, forcing them to obtain special permission to receive services elsewhere.

I would often refer people to detox at the public hospitals if they couldn’t easily qualify for Medicaid, particularly immigrant participants. Only public hospitals would accept people who were not eligible for medical insurance. Though the detox program at Lincoln Hospital no longer incorporated revolutionary political education, it remained open and available over three decades after the Young Lords’ takeover. Lincoln also hosted a detox-focused acupuncture training program where Isaiah and many other syringe exchange workers had been trained.

I would follow up on my referrals by calling their detox programs after a couple of days. If the detox wasn’t going to find them a rehab program, I would help the participant find one. Detox addresses the medical issues of drug withdrawal. Rehab offers some of the skills necessary to stay clean. For the majority of my referrals, participants would be back on the streets a few weeks later. Our syringe exchange was always available, uncritical and nonjudgmental, providing clean syringes to help protect people injecting heroin from HIV and Hep C transmission.

_____

Syringe exchange programs were established in cities across North America in the late 1980s by activists combating the devastation of the AIDS epidemic. Heroin users in the late 1980s and early 1990s were dying of AIDS at staggering rates. Clean syringes saved lives far more effectively than any other intervention. Many of the early syringe exchange programs in the US were illegal. Volunteers faced the risk of incarceration or losing their medical licenses. Heroin users politicized by the AIDS movement staffed the exchanges themselves, alongside nurses and doctors, anarchists, and other activists concerned with the racial and class divisions within the AIDS movement.For anarchists, the exchanges were a form of radical mutual aid free of the moralism and condescension of most social services. AIDS organizing groups fought for syringe exchanges, alongside campaigns against homelessness, police violence, and AIDS criminalization, and to defend the rights of sex workers. The AIDS movement was largely unable to build ties with the now-weakened labor movement or civil rights organizations. Decades of economic crisis, criminalization, and the collapse of the left had effectively severed the solidarity between wage workers and the lumpenproletariat within Black and brown communities.

Syringe exchanges were part of an ethical and political vision known as harm reduction. Harm reduction stands in sharp contrast to “abstinence-based” drug treatment, and the criminalization of drug use. Most social services — housing programs, mental health counseling and treatment programs, cash transfer benefits, even food programs — ban all people who are known or suspected to be using any street drugs or off-label medications. Drug treatment programs in particular, like the rehab programs I would refer participants to, are based on authoritarian treatment models founded on a principle that people forfeit their right to make their own decisions when they become addicted to crack or heroin.

Harm reduction activists recognized that many people aren’t ready or able to discontinue drug use altogether. Demanding abstinence as a precondition to accessing services further isolates drug users, contributing to more destructive use patterns. These programs instead sought to reduce the harms both directly associated with drug use and those stemming from the social stigma around it. Harm reduction seeks to aid users in pursuing their own self-identified goals and needs that may not include abstinence at this time, or ever. This approach calls on an ethical and practical orientation that is as rare in social services as it is in radical politics: engaging the painful, traumatized, and self-destructive parts of people with care, taking seriously the possibility of transformation and healing, without a narrow, preset judgment about where people have to be now, or where they are headed.

“Our revolutionary politics must embrace the many broken and miserable places inside ourselves.”

I first became interested in harm reduction while living in Philadelphia. I had been transitioning my gender, and got my first white-collar job providing HIV services to other trans people. I was involved in the anarchist scene, but was rethinking my commitments in light of the sexism and transphobia I experienced coming out as a woman. While organizing with homeless trans women around shelter access, I was also becoming increasingly frustrated with the politics of social work. Around that time, a friend in Philadelphia killed herself, and I came to see our scene’s intense moralistic judgements of each other as partially to blame. We could either love or critique, but rarely do both together. I was dealing with my own mental health challenges, and found little understanding in my radical circles as I sorted through the contradictions of how to get care. I vacillated between feeling ashamed that I couldn’t figure out my shit right away, and posturing that I didn’t have any problems to begin with. Harm reduction seemed to offer a path towards a different sort of practice: an alternative ethical framework that allowed us to stop constantly judging others — and ourselves — according to the rigid criteria of political righteousness. Instead we could learn to care for each other with dignity, to challenge our capacity for harm by lovingly welcoming the most painful parts of ourselves.

From my coworkers at the syringe exchange who had spent much of their lives as dealers and users, I saw how harm reduction had helped politicize their experiences, transforming individual misery into a collective practice of solidarity and a basis for social critique. From my coworkers and harm reduction trainings, I learned how to relate to someone having a very rough time in a way that was relaxed, warm, and built a connection; a crucial skill in most political activity. I learned a lot about the street drugs popular in the Bronx, and the many ways drug use is woven through daily life. My coworkers taught me a bit more about how to love well in this difficult and painful world.

_____

In the last three years, the growing rates of overdose and suicide have lowered American life expectancy. This is the first decline in US life expectancy since the height of the AIDS crisis, and the most sustained decline in a century. Opioids now account for more American deaths than car crashes, gun violence, and HIV.

For many, opioids are a form of refuge from ongoing social disintegration. Decades of deindustrialization, wage stagnation, poor access to healthcare, and weakening unions came to a head after the 2008 economic crisis. People have turned to prescription painkillers to manage workplace injuries, depression, and untreated health problems. In the words of one public-health study, opioids serve “as a refuge from physical and psychological trauma, concentrated disadvantage, isolation, and hopelessness.” A 2017 study by the National Bureau of Economic Research showed that when the unemployment rate rises by 1 percent, emergency-room visits increase by 7 percent and the opioid-related mortality rate rises by 3.6 percent. Two economists recently coined the phrase “deaths of despair” to describe this loss of life.

As the crisis of capitalism and working-class life deepens, insurgent movements will need to grapple with drug addiction. Today we need a practice of liberation that recognizes and embraces the fundamental dignity and potential revolutionary agency of drug users and calls on new approaches to interpersonal care, mental illness, and profound personal misery.

We need a communist politics that does not assume respectability or stability, that does not divide the world between the innocently poor and the chaotically dangerous. When refusing their imposed disposability and isolation through revolutionary activity, junkies and their friends move towards a communism not based on the dignity of work, but on the unconditional value of our lives. Our revolutionary politics must embrace the many broken and miserable places inside ourselves. It is from these places of pain that our fiercest revolutionary potential emerges. We need a communist politics that welcomes us all and engages us fully as whatever we are — as freaks and fuck-ups, as faggots and trannies, as wreckers and miserable wrecks, as addicts and crazies. We need a junkie communism.