State repression begets the militarization of revolution. And yet, militarization itself incubates counter-revolution. In the Syrian experience since 2012, we hear the questions future revolutionaries must answer.

I grew up in Syria. In state-run schools, we were reminded daily that we received free education thanks to the Ba’ath party’s revolution in 1963. We should be grateful, our teachers told us. In the fourth grade, like millions of students across Syria, I memorized songs praising the Ba’ath Party and its leader, Hafez al-Assad: We shine like the morning, we carry the gun / Our blood will water the soil. A loyal Syrian must recite quotes by the party leader, quotes memorized from a 150-page book entitled Nationality. In exams, one could be penalized for misremembering a single word.

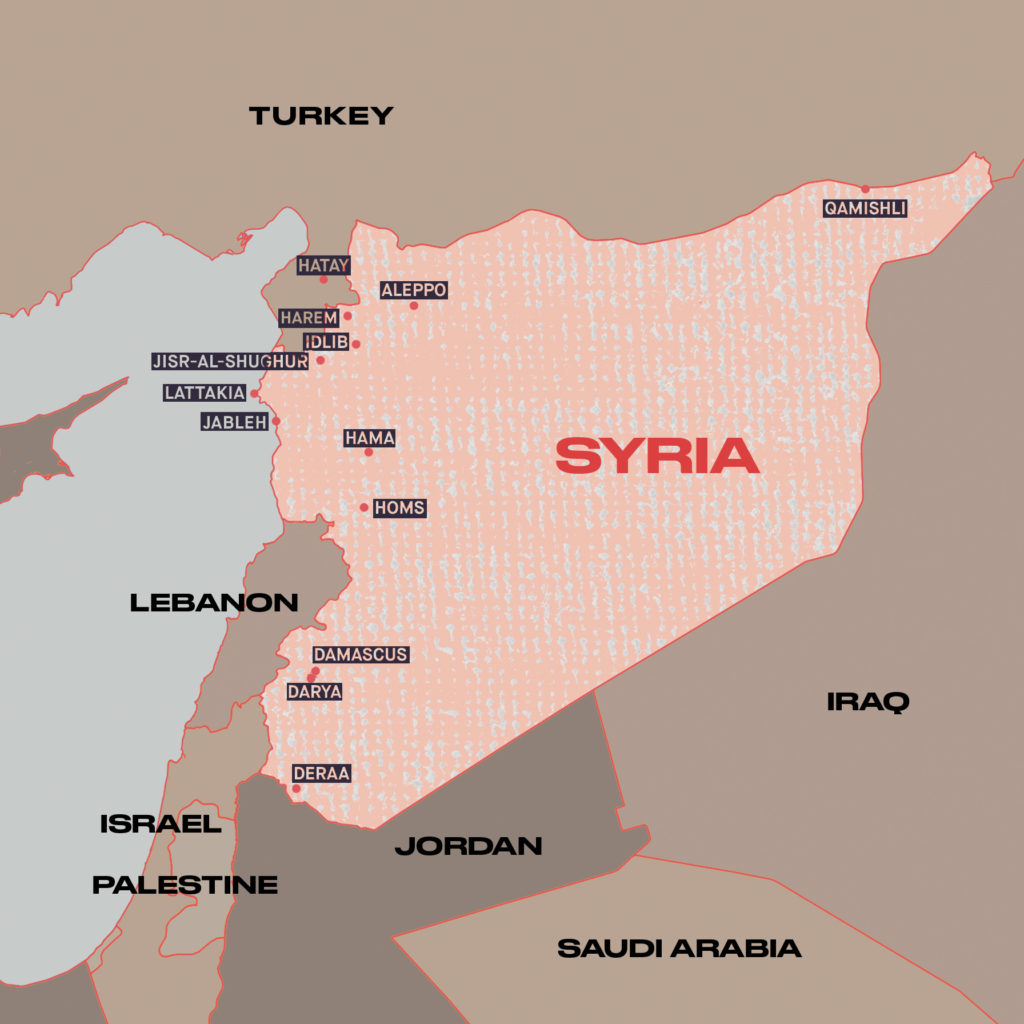

In government strongholds like my hometown, Jableh, in the Lattakia district, the line between support for the government and religion was always blurred. For Alawites like us, members of a previously persecuted minority, Hafez al-Assad’s seizure of power in the 1970s through a military coup was the reason for our survival. Without him, we Alawites would have remained in the mountains. Growing up Alawite, therefore, meant being reminded constantly of the government’s protection. Any attempt to overthrow the government should, according to this logic, be considered an attempt to kill us all. The choice was between the Assad regime or death.

I grew up believing that all other ethnic groups might kill us if they had the chance. And then, one day in eighth grade, it seemed that nightmare was coming true. In 2004, the Kurdish uprising in Qamishli happened. Following the requisite flag salute, the principal announced that our school trip was canceled because “there is trouble in the country.” Later, I overheard someone in the yard exclaim, “The Kurds are coming to kill us!” We were told that the Kurds were planning to target Alawite women. The teacher described an Alawite commander who the Kurds had tied to the back of a car and dragged through the streets of Qamishli until his flesh came off.

Every attempt to rebel against the system was portrayed as a threat to us all. The walls have ears, we were told. You must not criticize the government and its atrocities even from within the safety of your own home. Political activities were prohibited. The only vote we cast was for the Arab version of American Idol.

Despite this profound repression, some dared hope for change. This hope was sparked in 2000 when Bashar al-Assad, a young doctor living in the UK, inherited the presidency from his father and promised Syrians more political freedom. People optimistically declared a “Damascus Spring.” Their hopes were mistaken, however, and the new president turned out to be just like his father. In 2003, Dr. Kamal al-Labwani and twelve other political and human rights activists were detained for attending a meeting of the opposition in Damascus. They were punched, kicked, slapped, humiliated, and deprived of access to medication. One detainee, Riad al-Turk, was 80 years old and had cancer; he was deprived of medical attention and nearly died. According to a report by Human Rights Watch, the activists were forced to sign confessions stating that they had taken money from foreign countries in order to help the Kurds achieve independence.

Six years later, in 2009, accusations of the same kind were repeated on Syrian state TV, accompanied by a picture of an 18-year-old blogger named Tal al-Mallohi.

In her blog, al-Mallohi wrote about her vision for the country, what she didn’t like about the culture, and how excited she was to grow up and make a change. Her blog posts were hardly works of fire-breathing militancy. The Syrian government, however, had a different view. The Syrian Foreign Minister claimed that she was forced to be a spy for Israel after they blackmailed her with sex tapes. She was the youngest of many who were detained for speaking their minds. And people knew that if they questioned the government narrative around her case, they would face the same fate. Al-Mallohi was sentenced to five years in prison but ten years later she is still behind bars.

A Double Spring

In late 2010, as the Arab Spring swept first through Tunisia and then Egypt, Syrians watched news reports aired on pan-Arab television news outlets, such as Al Arabiya and Al Jazeera, showing ordinary people taking to the streets and overthrowing dictatorships. Out of earshot of the regime, Syrians began to wonder if this could happen in their own country. Many thought it was impossible given the unique repressive powers of the Syrian government, but, as it turns out, they were wrong. The winds of change reached Syria in March 2011.

The exact origins of the Syrian revolution are highly contested, with some dating it to March 15 and others to March 18.

On March 15, a group of thirteen intellectuals organized a small protest in the old city market of Damascus. “God, Syria, freedom,” they chanted, replacing “Bashar” with “freedom” in the official chant “God, Syria, Bashar.” To the government, that change in wording was a declaration of insurgency, and the intellectuals were immediately detained.

I remember sitting in a cafe in Lattakia and feeling terrified as I clicked the link to the video of that protest. I knew that just watching it could lead to my detention, so I put on my headphones and opened the video behind a VPN, or virtual private network, making it impossible for the regime to locate me through my computer’s IP address. The number of views on YouTube quickly reached one hundred thousand in fewer than two hours. In no time at all the video was being aired on news channels such as Al Arabiya and Al Jazeera.

“Political activities were prohibited. The only vote we cast was for the Arab version of American Idol.”

Was this viral video the spark that set the Syrian uprising ablaze? Many would answer yes, but while that video was going viral, events far more consequential for the uprising were unfolding south of Damascus. Two days before the protest, on March 13, a group of schoolchildren in the town of Daraa, sixty-eight miles south of Damascus, were detained after writing on a wall a slogan they had heard on TV: “The people demand the fall of the regime.” The children probably had no clue that writing such a slogan would lead them to have their skin burned with cigarettes and their nails pulled from their fingertips. Security forces tortured them mercilessly to discover from whom they had learned this slogan, ensuring, ironically, that it would soon be on everyone’s lips.

On March 18, the children’s families marched together to the security branch, demanding the release of their children. One officer reportedly told a father: “Go home and forget that you had a child. Just make another one. And if you cannot, send me your wife. I will do the job for you.” This was the beginning. Daraa is a small city compared to Damascus and Aleppo, consisting mainly of two tribes. Relationships among residents are tightly knit: everyone knows everyone, and everyone is related to everyone else. In such communities, a man’s wife is his honor, and insulting a man’s honor is unlikely to be ignored. Therefore, it was no surprise that the whole city took to the streets against the security forces who had detained and tortured the children and then insulted their families.

On March 19, hundreds of thousands marched in Daraa, angrily shouting “we want justice,” demanding the immediate release of the children, and cursing the mohafez (governor). Shortly after the protest began, security forces appeared. Shooting live ammunition into the crowd, they killed four people. As with the protest days before in Damascus, video of the event got out. Some of the protestors had filmed these killings with their mobile phones and uploaded the scenes to Facebook and YouTube. Hours later, the whole country was watching the killings, which were quickly covered by foreign and pan-Arab television news outlets.

Within days, protests swept Syria from north to south. Thousands marched, chanting for Daraa. These first chants were calling neither for regime change nor the removal of Bashar al-Assad. Nor were they calling for bread, as in Egypt. The demands, however, were clear and specific: protestors wanted the release of the children, the resignation of Daraa’s governor, and accountability for the protestors who were killed in Daraa.

Security forces in cities across the country took a page from the Daraa playbook, firing live ammunition at protestors in cities large and small. Dozens of people were killed within the first few days. By the end of the first week, the chants had changed. Now the people, following the brave schoolchildren, demanded the fall of the regime.

Many observers and participants, myself included, argued behind closed doors and on social media platforms that the uprisings would have lost momentum had the president replaced the governor of Daraa and held the murdering police officers accountable. But Assad the Younger followed the dictum established by Assad the Older: just kill them all. This approach poured gasoline on the fire, the brutality of the police swelling the ever-larger and ever-angrier protests. Each day, there was a funeral for a protestor killed the day before. The funeral would turn into a protest, and the pallbearers would find themselves inside the casket the next day, surrounded by an even angrier crowd. People would attend funerals without knowing who had been killed—their main aim became the protest itself.

During that time, activists used Skype to coordinate protests. Because most organizers were hiding from the Syrian government, which had established checkpoints everywhere, it was extremely difficult for them to meet physically in one space. Every city had its own Skype group, and organizers were added by someone who trusted them. We mostly used nicknames. Mine was “Loubana al Ali.” The groups included everything: news, alerts if a police patrol was approaching the area, video clips from protests.

Most of these videos were taken by people who only had cell phones, marking the date and place of the incident by shouting it out over the footage. Those behind the cell phones would come to be called “media activists” by news outlets, though they were protestors with no media training and no special capacities beyond a working cell phone and a good home internet connection. With journalists prohibited from entering the country, these amateurs were the only source of news on Syria for the outside world.

Throughout these protests, people were unable to successfully occupy squares, as had happened in Egypt and Libya, despite massive numbers of supporters. (Hama, for example, had a turnout of more than half a million people for one protest.) People tried to copy the Tahrir mode with tragic results. Two examples include an occupation in Homs, and another in my hometown, Lattakia. In Homs, the target for the attempted occupation was a famous square called The Clock. People gathered after the evening prayer and remained there. By midnight, nearly two hundred thousand people had gathered. The gathering didn’t last long, however, and by night’s end nearly a hundred protesters lay dead. In Lattakia, the same thing occurred: protestors were shot and, afterward, fire fighters arrived to wash their blood from the streets. Nonetheless, the smell of blood lingered for days. We all knew what had happened, but no one could say anything; we quickly crossed the neighborhood where the massacre occurred and pretended we knew nothing.

Not only did protestors face brutal repression in the streets, but the groups that organized them were in constant danger. Government informants were everywhere, and the regime detained everyone it suspected of association with a local coordination council (LCC). Detainees would be tortured until they confessed the names of all their associates—hence the importance of nicknames. Nicknames were used not because we distrusted each other, but because no one knows what they might do if tortured. However, the regime killed people whether they provided information or not, and only the lucky ones made it out alive.

Rami, a friend who founded a Facebook page that posted daily updates on checkpoints, was detained in January 2012. A week later his dead body was returned to his family: not only had his nails been ripped off but his fingers were gone, too. When we visited his mother, she told us his eyelashes had been burned by cigarettes. In order to bring his body home, she said she had signed a document stating that her son had been killed by “terrorists.” Hundreds of activists met a fate similar to Rami’s. Even if someone didn’t participate in a protest, security forces might detain someone simply for being from a rebel village. Everyone was a suspect. That people decided to arm themselves and fight back in the face of such repression surprised no one.

The Silent Majority

You might be forgiven for thinking that, after all this horror, the entire country would be against the government and sympathetic to those calling for justice, reform, and dignity. But, in fact, the majority of the country did not join the uprising. This silent majority comprised three rough categories: the hardliners, the bourgeoisie, and the undecided. Hardliners knew exactly what was happening and supported it unequivocally. Without Assad, they believed, there was no country. The bourgeoisie, unlike the hardliners, cared only about the security of their own families and businesses. They refused to pick a side. People in this category were the first to flee the country. And the undecided, finally, could not figure out what was happening. However, many members of this group made up their minds rather quickly and joined the hardliners. Their conversion to opponents of the uprising was mainly achieved by the media narrative propagated on state television, as well as by the militarization of the conflict.

At first, Syrian state TV ignored the demonstrations. No breaking news interrupted the usual schedule of soap operas, cooking shows, and animal documentaries. Viewers watching Syrian TV in other countries would have no idea that the Arab Spring had come to Syria. However, the regime could not ignore the uprising for long. Those who lived in heated zones, like Homs and Lattakia, complained on social media that they had to watch Lebanese and Qatari channels like Al Jazeera, Al Arabiya, and LBC (Lebanese Broadcasting Corporation), in order to know what was happening.

“Security forces tortured them mercilessly to discover from whom they had learned this slogan, ensuring, ironically, that it would soon be on everyone’s lips.”

On March 22, Syrian state TV aired a clip from a protest in Al-Midan, a neighborhood in Damascus. The news anchor stated that they were thanking god for rain, not protesting. Later, the news programs offered conspiracy theories, often involving Qatar. Another clip was aired but the anchor asserted that the footage was fake, filmed in Qatar. Other programs stated that Qatar had been sending money, military advisors, and drugs into the country in order to cause chaos. Syrian state TV aired what it called a confession by a terrorist: someone who appeared to be mentally unstable confessed to being paid by Qatar to shoot at police forces.

People believed it. In Jableh, my hometown, people were convinced by these fabricated reports, terrified by the campaign of disinformation. Those who were convinced of the conspiracy started patrolling the streets, asking us to lock our doors. “The Salafists are coming to kidnap us,” they insisted. Syrian TV painted what was happening in the country as uprising against secular government. Everything was framed as being about Islamists. “After me, the deluge,” Assad might have said, and many believed that they had to choose between Islamist chaos or the government of Assad. Pro-revolutionaries found they not only had to dodge bullets and evade detention but combat an equally deadly state narrative on social media and in the streets. It was not long, however, before the government narrative became reality. Though the participation of Salafists was minor at the beginning, it grew quickly.

Civil War

The military wing of the uprising, The Free Syrian Army (FSA), did not form until July, but the uprising had become militarized before their formation. The first incident of armed self-defense took place in a small village on the Turkish border in Idlib province, Jisr al-Shughur.

On June 4, 120 government soldiers were killed in Jisr al-Shughur. Two days later the government announced news of their deaths on state TV, broadcasting the soldiers’ funeral live. The TV report claimed that the soldiers were in their base when a group of terrorists attacked them. Local activists rejected this account, saying that the soldiers had shown up to the funeral of a young man killed the day before, a funeral which had, following the new custom, grown into a massive protest. More than fifteen thousand took to the streets that day. Activists claim that as the soldiers prepared to fire on the protest, someone shot them first.

This was just one take on who had killed the soldiers. Some suggested that the soldiers were killed by fellow soldiers who refused to watch innocent people massacred. It’s important to note here that weapons are abundant in cities on the border. Every house has a gun. Whatever the true story, this incident opened a new chapter in the uprising, with two important consequences. First, many Syrians saw the names of the dead soldiers as confirmation of the government narrative, which aligned undecided Syrians with the regime. Second, these events created a split within activist circles, as parts of the movement took positions for and against the use of arms.

Many activists, having protested peacefully for the previous three months, became enthusiastically supportive of the idea of armed self-defense. They felt that through the use of violence, justice was finally being served for those killed by the police forces. Other activists argued that armed self-defense was the beginning of the end for the revolution, and that the chaos introduced by guns would ultimately empower the Syrian government. But violence by the regime overwhelmed most commitments to abstract strategic ideals. Fighting back was a matter of survival.

On July 9, days after the incident in Jisr al-Shughur, a video circulated online of a Lieutenant Colonel in the army named Hussein Harmoush. In it, he announced his defection from the Syrian Army because of the killing he had witnessed at Jisr al-Shughur. Some journalists suggested that Harmoush was responsible for the resistance in Jisr al-Shughur, that he was the first army soldier to protect protesters and fire at government forces. Following this, he became an icon for soldiers who wanted to defect. His defection made many feel like it was not too late for the Syrian Army to side with the uprising, as had happened with the Egyptian Army and the Egyptian revolution. Many soldiers followed Harmoush’s lead, defecting by sharing identical videos. They would hold their military ID in hand and stare straight at the camera: “I defect from the brutal Syrian Army. We are not serving the country. We are helping one person to stay in power. I refuse to shoot at peaceful protests, therefore I defect to join the Syrian uprising.”

As soldiers defected, they brought their ammunition and weapons with them, joining small groups of other defectors formed in their hometowns. These groups brought together people from different religious backgrounds and different walks of life, from doctors to construction workers, who believed in the right to self-defense. Although they had different ideologies and different visions for the future of the country, they were united by the belief that peaceful uprising could never overcome the brutality of the regime.

Between July and November of 2011, the armed rebels’ main mission was to protect protestors from government attacks. Rebel groups, comprising army defectors as well as armed civilians, were praised by the larger Syrian uprising. Protestors chanted and sang for the armed rebels. They felt protected by them. Many activists completely supported the armed resistance, and hesitated to attend protests not protected by armed rebel groups, fearing the brutality of the regime. Meanwhile, Turkey opened its borders and thousands of Syrian refugees fled north to escape the violence inflicted upon them. Among these refugees were army defectors who crossed into Turkey with their families. In border towns like Hatay—approximately a two-hour drive from Idlib—leaders of battalions of these defectors met and organized in safety from the Assad government. As time went on, they were able organize in Turkey and cross into Syria to engage the regime. Hence, the first rebel-held areas emerged along the Turkish borders.

October 27 marked the first official meeting of army defectors in Turkey. Colonel Riad al-Asaad declared in a written statement that they hoped for material support in order to topple the government. “We ask the international community to provide us with weapons so that we, as an army, the Free Syrian Army, can protect the people of Syria,” he said. “If the international community provides weapons, we can topple the regime in a very, very short time.” This was the first public plea by Syrian rebels. It was quickly criticized by human rights activists such as Rami Abdul Rahman, the head of the UK-based Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, who noted, “the Free Syrian Army is giving people false hope that they have the required strength to topple the regime . . . One must keep in mind that the formal Syrian army is comprised of more than five hundred thousand soldiers, not to mention the hundreds of pro-government shabeeha [thugs]. So betting on the ability of the Free Syrian Army to overthrow Assad is a losing bet.”

Although Turkey did not admit to providing the FSA with military support, it did openly provide refuge for army defectors and a safe place where rebel commanders could meet with their donors. As one FSA member stated, “Turkey gave us the freedom to move.” In addition, Turkey became an important conduit for financial flows from countries like Saudi Arabia and Qatar. Despite ideological disagreement with Saudi Arabian or Qatari models of governance, Syrian rebels desperately needed material support. As they saw it, they had no choice but to take money and weapons from these countries.

“The funeral would turn into a protest, and the pallbearers would find themselves inside the casket the next day, surrounded by an even angrier crowd.”

By the middle of 2012, the FSA was able to gain control over some key villages in Idlib, eastern Aleppo, and large parts of the countryside surrounding it. Instead of simply protecting protests as they had done previously, the FSA was now on the offensive, bringing the fight to the regime and establishing rebel-held territories. These areas became safe havens for those who opposed the regime. International NGOs, like the International Media Corps (IMC), opened and funded offices in rebel-controlled areas. Locals held elections and governed through what they called local councils (majlis mahali). Media activists started to print their own newspapers for the first time in decades. People experienced what it was like to write an article without fear of detention and persecution. Banners flown from buildings in rebel areas spread through social media, just as, conversely, the virtual Skype groups materialized into real, physical spaces. In Aleppo, media activists opened and ran Aleppo Media Center. Media centers in rebel-held areas were frequently housed in the residences of people who had fled the chaos or been killed. There was often nothing in them but satellite internet, sofas, and sandbags on the windows to protect against government snipers. These small centers became the source of most of the news coming from Syria.

Turkish borders had more or less vanished. In early 2013, it was easier to enter the country via the smuggling routes than to go through passport control. Journalists and freelancers from around the world landed in Turkey and crossed into Syria, where the rebels welcomed them and offered them protection. The rebels were as desperate for media attention as they were for material support.

Journalists and aid workers were not the only foreigners who took advantage of the open borders, however. During this time, more than twelve thousand foreign fighters poured into Syria. If you passed through a Turkish airport in 2013, you would have noticed many of these fighters in the baggage claim areas and terminals of border airports; they sported large beards and carried big backpacks. Many Syrians were aware that open borders posed a danger to the conflict, but no one from the opposition could say a word. Closed borders for foreign fighters meant closed borders for everyone else. Turkey was the only way in or out for the rebels.

There was an explicit quid pro quo involved. Turkey wanted ally groups in Syria in order to protect its borders from the Kurds, whom it had been fighting since 1978. And radical jihadists, given their experience in other conflicts, turned out to be the best anti-Kurdish option. In the fall of 2013, Ahrar al-Sham, an armed Salafi group supported by Turkey, was the main force that fought the YPG and other Kurdish groups, in towns along the Turkish border. But the jihadists were not just Turkish allies. They coordinated with other rebel groups and, eventually, took over the liberated areas.

Many activists and rebel commanders fought these Salafi groups, and hundreds of activists in rebel-held areas were later detained and killed by groups like the Al-Qaeda affiliate Jaysh al-Islam. Other rebels, however, welcomed the Salafists and considered them allies. Al-Qaeda affiliates did not simply emerge fully formed but grew by exploiting massive discontent in the context of government repression, and further earned public support by being effective fighters. Islamic State, unlike other jihadi groups, had its own front in the east and did not rely on alliances.

In the strongholds of the rebellion to the west, Al-Qaeda affiliates had the most military success for several reasons. They were the most experienced units in the field, with the majority of their members having combat experience in Iraq, Afghanistan, or Chechnya. In their fight against Assad’s Russian-backed allies and Shia militias, like Hezbollah, Syrian rebel groups needed the experience in guerilla-style combat that Al-Qaeda affiliates could provide. Highly disciplined, accustomed to fighting in harsh terrain, the Salafi units continually outperformed their Syrian rebel counterparts. In particular, fighters from Chechnya were highly effective in battles against the Russian-backed allies, given their experience with Russian military technology.

As a consequence of their ineffectiveness in the field, the FSA began to lose public support from fighters as well as from locals in the villages they controlled. People were frustrated by the FSA’s inability to restore law and order, and rebel-held towns saw civilian protests against the corruption of the FSA affiliates. During that period, many rebels would raise money by fining civilians at checkpoints. Hasan Jazara, a famous leader in eastern Aleppo during my time there, led a small brigade in looting houses, shops, and factories. Dozens of factories in eastern Aleppo were looted, their goods sold in Turkey.

There was no means of redress for FSA abuses. Without clear leadership within the rebel groups, it was impossible to hold rebels accountable, and citizens became increasingly frustrated with the FSA. Local councils, in charge of schooling and aid distribution in rebel areas, had little real power and were unable to counter corruption. Kidnapping, theft, looting, and robbery were rampant in places such as eastern Aleppo. When I worked there, I was more scared of being kidnapped by groups pretending to be the FSA than I was of government bombardment. Meanwhile, the Al-Qaeda affiliates were viewed by the public as more disciplined and less corrupt than the FSA, and better able to offer security.

Today, the regime has reconquered most of the rebel-held territories, and those that the regime has not reconquered are under the control of Al-Qaeda affiliates and other Salafi groups. According to the Syrian Center for Policy Research, an independent Syrian research organization, the death toll from the conflict as of February 2016 was 470,000. There are also more than 117,000 people still being held in government detention facilities. Among the activists mentioned earlier, whether in the local coordinating councils or media groups, those who were not killed or imprisoned by the regime are now in exile. Many are still working closely with international legal advocates to seek justice for those who were killed and to secure freedom for those still detained. For the most part, surviving activists have been sucked into a deep depression, watching from afar as towns and villages once controlled by the rebels have fallen back under government control. Metal statues of Hafez al-Assad have been rebuilt in squares where protestors gathered in 2011. And, where once the anti-regime graffiti of brave schoolchildren in Daraa perhaps precipitated the revolution, a recent video showed children in the schoolyard there chanting for the immortality of the president.

I have been living in exile in the United States since 2014, and most discussions I have witnessed in the US about Syria’s war and its refugee crisis amount to simplistic arguments ignoring the emancipatory struggles that preceded these recent years of tragedy. In order to understand the nature of the Syrian conflict, it is essential that we remember the first years of the uprising, and, through remembering what took place between 2011 and 2014, dispel the myth that Syria has always been a proxy war or has always been a struggle between a secular government and jihadis. To ignore the years which lead Syria from a democratic uprising to a bloody proxy war is to read history backwards.