Against the landlords and the police, in cities poisoned by wealth.

It is not easy to convey the wretchedness of everyday life in the San Francisco Bay Area right now. A recent poll gives some hints, however: 44 percent of those surveyed are considering moving out of the area due to the high cost of housing. When people lose housing in the Bay Area, it’s a crisis on the level of a serious illness. For those who do find a new place within their means, it often takes months. Many accept housing they can’t afford because it’s all they can find. Others move elsewhere, or become homeless. From San Francisco to Oakland and beyond, homeless encampments spill out of every underpass, or sometimes take up temporary residence on neglected city-owned land. In an absurd cat-and-mouse game,these encampments are periodically pushed from place to place by the police and the Department of Public Works. There’s no shortage of precarious service work, though, which manages to keep most Bay Area residents too busy to begin to do anything about how fucked it all is. Here in the home of Google, the most common thing for people to type into their search bar is “Should I move out?” You can feel it on the streets, the stress, which no amount of legal weed or whimsical electric scooters can unwind. People are pulled taut, ready to snap. Meanwhile, the ultrarich are building their barricades. Incensed by the city’s plans to construct a 200-bed homeless shelter in their neighborhood, millionaire residents of San Francisco’s Embarcadero recently raised $60,000 through GoFundMe to challenge it in court.

It’s going to get worse, too, if things keep on this way. Lyft — regarded by some as the “ethical” alternative to Uber, by virtue of not being as famous for sexual assault and avarice — just went public, engorging itself with $24 billion. Overnight, six thousand of its employee-shareholders were knighted by Wall Street and made millionaires. Together, they could buy every single house currently listed in San Francisco. Behind Lyft, other “decacorns” (start-ups worth over $10 billion) stack up, like a string of jets waiting to land: Uber, Airbnb, Slack, Pinterest — each one filled with several thousand rich assholes. As with the mounting climate crisis, in which each new year portends unprecedented catastrophe, the damage this Category 5 hurricane of cash might do to the Bay Area housing market is hard to fathom.

“The story of the village is only one part of an ongoing epic of resistance and repression that the homeless and their allies are writing every day in the Bay Area.”

Last November, a thick blanket of black smoke covered the Bay Area for half a month, drifting downstate from the Camp Fire in Paradise, the worst in California history by nearly every measure. The streets of Oakland, that erstwhile capital of riot, were once again populated by harried mask-wearers, but this time there were no police to beat them senseless, only the unnatural disaster of a warming world in which, according to one scenario, the old forests of California will burn and burn until only charcoal deserts remain. In the Bay Area, twenty-nine thousand homeless people — some 70 percent of whom were formerly housed in the region — didn’t have the option of closing doors and windows to keep out the deadly air. The homeless are an index of evictions and displacements, of skyrocketing rent, in a part of the country where the racial and class composition has changed dramatically in the last decade. No surprise then that black people are overrepresented among the homeless by at least a factor of four.

During those smoke-filled weeks, the state did little to help those out in the streets. Mask Oakland, an autonomous self-organized group, leapt into the fray, distributing eighty-five thousand masks throughout the Bay Area, targeting the homeless population in particular. These efforts were made possible due to a growing network of homeless organizers and allies. A key part of this network, in Oakland, is The Village, a self-described “direct action that became a movement,” which began on the morning of Trump’s inauguration when one hundred people seized a small, derelict park next to an underpass and began constructing small homes from wooden pallets. Hundreds began organizing through the camp, which quickly added a score of small houses, tents, and RVs, along with a kitchen, meeting space, and medical tent. More than 130 homeless residents signed up for housing and services.

After thirteen days, The Village was evicted from this encampment, which residents had begun calling The Promised Land. Through consistent pressure on the city, the evicted residents were eventually promised another parcel of land, at East 12th and 23rd Avenue in Oakland, which organizers called Two Three Hunid Tent City. These promises proved false, however; after months of evasion and delay by the city, it was revealed that the site belonged to Cal-Trans (the freeway authority) and not the City of Oakland. During these deceptions, Oakland mayor Libby Schaaf attempted to neutralize The Village’s direct action tactics by establishing three of its own “Tuff Shed” camps — corrupted imitations of The Promised Land and Two Three Hunid. Organizers with The Village and former Tuff Shed residents describe them as “torture camps.”

SOME FIRES

The efforts of groups like The Village and Mask Oakland resemble the autonomous, self-organized relief projects that have sprung up in response to recent disasters, from Puerto Rico to California and elsewhere. Last November, while encampment residents and supporters in Oakland did their best to protect one another from the toxic smoke, many people in the immediate vicinity of the fire were displaced and forced to organize into makeshift camps of their own. Largely rural Butte County, where Paradise is located, was already enduring a housing crisis before the Camp Fire ignited. In September, Butte’s Board of Supervisors had declared a countywide shelter crisis. An official estimate in 2017 counted 1,983 homeless people, 856 more than the previous count in 2015. Over the same period, median rent increased 53 percent, indicating the extent to which the rent crisis in urban markets like the Bay Area is part of a larger crisis affecting rural renters as well, an unnatural disaster spanning the state and the nation. Meanwhile, median incomes in Butte grew only about 7.5 percent. When rents increase but wages don’t, proletarian tenants get displaced — and the poorest can’t afford new housing.

When the fire came, it displaced fifty-two thousand people, killed eighty-eight, and incinerated fifteen thousand homes. Many of those displaced came to Chico, the county’s largest city, joining those already displaced by the slower burn of the housing crisis. Facing a laggard and inadequate response by state and nonprofit bureaucracies, some of the displaced chose to squat a Walmart parking lot. There, they established a communal encampment and donation center, Wallywood, which, unlike the bureaucrats, served homeless people indiscriminately, whether they had been displaced by fire or rent. One estimate counted more than a hundred occupants in Wallywood, with many more benefiting from the mutual aid infrastructure.

According to the first of two dispatches by mutual-aid organizers, Wallywood immediately faced threats of eviction, not only from Walmart’s corporate head of security but also from the state and from employees of nongovernmental organizations who shared with Walmart what scholars of disaster have called “elite panic,” which sees in autonomous disaster relief efforts only a threat to social order. Wallywood was evicted in late November 2018, three weeks after the fire had started, despite the fact that authorities had no plan to offer housing. Thus did order prevail in Chico. At the onset of the Camp Fire, acting governor Gavin Newsom had extended to Butte and other fire-affected counties a state of emergency and a ban on price gouging, prohibiting rent increases above 10 percent. But this was too little too late for county residents who had been gouged by the housing market well before the fire began.

While these makeshift camps provide refuge from the flames, they are themselves vulnerable to catching fire, with so much flammable material, inadequate spaces for cooking, and no proper heating. Two months before the Camp Fire, in September 2018, Two Three Hunid went up in flames, displacing residents. This gave the city an excuse to continue what writer and activist Jaime Omar Yassin has called “Tuff Shedification.” On October 19, the same day the United Nations released a special report on homelessness that singled out the San Francisco Bay Area as especially cruel and inhumane — comparable to the worst of the developing world — one of the largest homeless encampments in Oakland received notice that it would be evicted in five days. This camp was situated on an embattled, government-owned piece of land, the East 12th Remainder Parcel, long slated for luxury development. The Village and other groups in the newly formed Landless People’s Alliance held a rally, eventually organizing fifty people to show up and resist the eviction. With their presence and the accompanying media coverage, the city backed off.

In the wake of this win, The Village went on the offensive: on October 27 they established an encampment at a new site, calling it Housing and Dignity Village. They requested donations from the community and issued demands around housing justice and public land use. The city responded with an eviction notice, but this time the eviction process ended up in court, where hope often dies. A US district judge vindicated the city’s position, arguing that it could evict Housing and Dignity Village as long as it provided alternative shelter for the displaced residents. But as Needa Bee, an organizer with The Village and a plaintiff in the case, pointed out, the city does not generally shelter tenants it evicts from government-owned land. Most of those who were evicted on December 6, when the city cleared the camp, have remained on the streets.

RENT POLITICS

The story of The Village is only one part of an ongoing epic of resistance and repression that the homeless and their allies are writing every day in the Bay Area. While much of this work long predates the current housing crisis, there has been a surge in organizing lately. This is an inspiring development, but it remains small in scale relative to the problem itself. In 2017, there were twenty-nine thousand people without housing across the Bay Area, according to the Homeless Point in Time Count, though some say the number is much higher.

Responses to homelessness like the Tuff Shed program, paltry at best and violent at worst, are one aspect of the state’s woeful effort to address what it terms a “shelter crisis.” As in Butte County, where local governments have claimed they cannot afford to shelter the homeless in buildings that meet health and safety requirements, the state legislature has permitted some cities and counties to provide unhealthy and unsafe “emergency shelters” if they declare a shelter crisis. Under California’s 2017 Homeless Emergency Aid Program, declaring a crisis not only allows localities to construct emergency shelters, but also to apply for a piece of $500 million in one-time funding for housing vouchers and rehousing. But vouchers do little good if, as is common with Section 8 housing vouchers, landlords can refuse to accept them and often discriminate against those who pay with them. In other words, the shelter crisis can’t be separated from a larger housing crisis.

The crisis of both housing and homelessness in California is so acute that it has become a key issue in local and statewide elections. In the Bay Area, mayoral campaigns have turned upon it. By reelecting Mayor Schaaf last fall, the Oakland electorate apparently decided to stay the course despite growing discontent over her handling of housing and homelessness issues. Schaaf’s challenger on the left, Cat Brooks, had convened a People’s Assembly on the Housing Crisis. The ideas and proposals discussed there became the basis for her own housing platform, which echoed the demands for “public land for public good” and “homes for all” made by The Village.

In San Francisco, a measure to double funding for homeless programs, Proposition C, won with more than 60 percent of the vote, but has since been stalled by a legal challenge to its constitutionality. Inequality in San Francisco has become so staggering that a split has emerged inside the tech ruling class, with one faction supporting Prop. C and its increased taxes. Apparently, some tech millionaires would rather self-tax than have to witness the wretchedness they have sown on the streets where they park their Maseratis. One of the biggest supporters of Prop. C was Salesforce CEO Marc Benioff; the company’s newly built tower is now the defining feature of the skyline in San Francisco, a topsy-turvy place where tech barons campaign side by side with the local chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America.

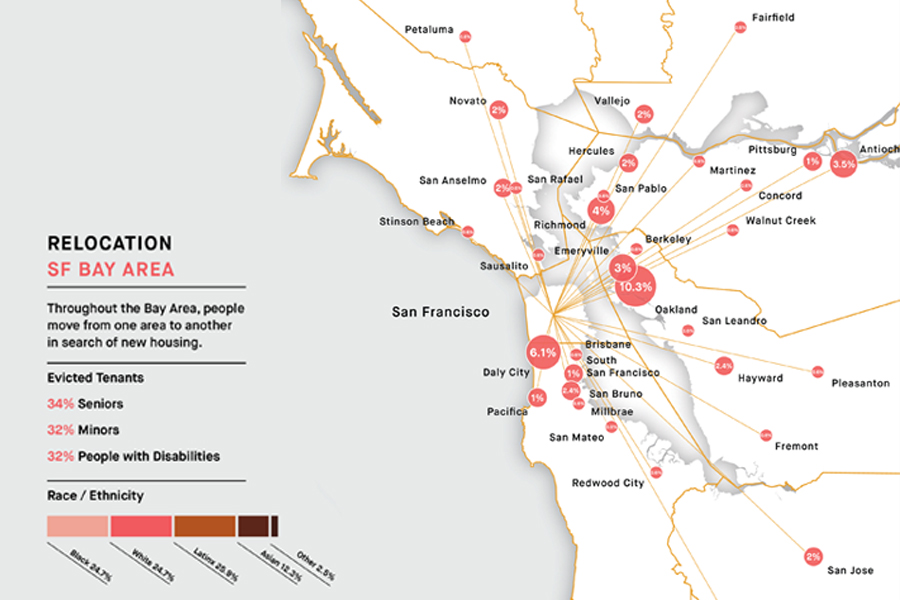

Map courtesy of Anti-Eviction Mapping Project

In California broadly, much of the energy of the tenants’ movement was absorbed by the campaign around Proposition 10, a 2018 statewide ballot initiative which would have eliminated the partial ban on rent control instituted by the 1995 Costa–Hawkins Rental Housing Act. Prop. 10 wouldn’t have expanded rent control directly; it would have merely repealed this ban on what kinds of rent control municipalities can impose on landlords. The Proposition failed, 41 percent to 59. Many attribute the failure to the same real estate and finance interests that created the housing crisis in the first place. One private equity firm, Blackstone, alone contributed $5.6 million to the campaign against Prop. 10. But the fact that nearly 60 percent of California voters opposed it suggests deeper social causes than the influence of corporate money.

Perhaps part of the problem is the persistence of home ownership and the “ownership society” ideology that drives it. In California, only 45 percent of people were tenants in 2018. After the subprime mortgage crisis, some commentators spoke of the “rise of a renter nation.” But the modest increase in the number of renters since then has only returned us to the previous status quo, before subprime mortgages temporarily swelled the ranks of homeowners.

Given who votes, it is in fact surprising that Prop. 10 did as well as it did. In the US, home ownership is the main vehicle for transferring wealth across generations, and therefore the central mechanism for reproducing class in its racial dimension. As historian Robert O. Self and others have argued, the ideology of ownership has made it so that even the poorest homeowners tend to imagine their interests as aligned with landlords rather than tenants, either because they identify racially with these landlords or because they share the same ownership interests. Furthermore, tenants who come from white and middle-class backgrounds tend to believe landlords when they argue that rent control actually raises rents by discouraging the construction of housing.

Perhaps Prop. 10’s loss, then, can’t be put down to spending by the real estate and finance lobby. Maybe the real takeaway is that the housing crisis is so bad that even massive corporate spending could not stop many homeowners from casting their ballots in favor of tenants.

There’s another story about Prop. 10 that’s worth considering. Some conservative commentators have attributed the entire existence of the repeal campaign to a single wealthy capitalist, Michael Weinstein, who’s been called the “CEO of HIV.” Known for his anti–real estate politics, Weinstein is the president of the AIDS Healthcare Foundation (AHCF), a group which donated at least $17 million to support Prop. 10. Many in the California tenants’ movement did not believe a repeal of Costa–Hawkins was winnable through a statewide ballot initiative. AHCF didn’t listen to them, however, and committed an initial $10 million to the effort. This essentially forced movement organizations to enter an unwinnable fight or else lose the confidence of their members, who hadn’t participated in the private strategy conversations and just wanted rent increases to stop.

DIRECT ACTION AGAINST RENT

Are there alternatives to doomed electoralism? In the past couple of years, I’ve begun to discern the contours of what some of these alternatives might be. I first started doing tenant solidarity work in 2011. Since then I’ve showed up for eviction defenses in Oakland and San Francisco. I’ve demonstrated outside the offices of eviction lawyers. I’ve canvassed for successful legal reforms that expanded local tenant protections. I’ve volunteered for the Oakland Tenants’ Rights Clinic of Causa Justa :: Just Cause. But it wasn’t until September 2017, when I attended the California Renter Power Statewide Assembly, that I felt the tenants’ movement might eventually do more than mitigate the crisis.

One of the main problems faced by the movement is overcoming the entrenched habits of the nonprofits that tend to monopolize housing activism and organizing. The people who staff these organizations know the limitations of the nonprofit model all too well — financial dependence on foundations, overworked staff, and political reformism, to name a few. In moments of acute crisis, which are also moments of opportunity for tenants’ movements, nonprofit organizations often can’t scale up to meet the needs of people seeking housing support. Looser organizations, like autonomous tenants unions, solidarity networks, and local and regional assemblies, seem to do better in these situations.

The 2017 assembly was held at a public high school in the Bay Area town of Alameda. A fellow attendee told me that Alameda was chosen because a campaign for rent control there had been narrowly defeated the year before. The hope was that holding the assembly in Alameda would send the message that the Alameda Renters Coalition wouldn’t give up the fight. At the high school, the bleachers were packed. Speakers called the assembly the largest yet for the contemporary US tenants’ movement, with more than four hundred people attending. (For comparison, around three hundred people attended a Renter Power gathering in Atlanta in 2018.)

The assembly seemed to embody two visions of what “Renter Power” means. One was focused on the electoral arena, in particular on mobilizing for the repeal of the Costa–Hawkins Act. The other was oriented toward building tenant organizations. Though these objectives are by no means mutually exclusive, organizing around statewide policy changes like Prop. 10 drains resources from more immediate fights against local landlords. The most persuasive case was made by the LA Tenants Union (LATU), which proposed a bottom-up strategy of organizing renters that seemed to have the potential to actually work. The subsequent failure of Prop. 10 has only confirmed my initial estimation.

As with labor unions, the strongest weapon of tenant unions is the strike. Rent strikes occur when tenants who collectively face unbearable conditions — harassment, rent increases, uninhabitable apartments, evictions — coordinate against their shared enemy, the landlord. Like the cost of rent itself, rent strikes are on the rise in the US, as tenants turn to newly available organizing tools. LATU is one of a handful of groups at the forefront of organizing a new wave of tenant unions. Using multilingual know-your-rights trainings to draw in different blocs of renters, the group now operates in eight different neighborhoods around Los Angeles.

The power of LATU’s model is illustrated by the strike they helped organize at the Burlington Avenue Apartments in the Westlake area of Los Angeles, perhaps the largest rent strike the city has ever known. As detailed in Warren Szewczyk’s article “Anatomy of a Rent Strike,” published at the local news website LA Taco, on February 5, 2018 around two hundred tenants of the Burlington Avenue Apartments were gathered outside their building, discussing the unlivable conditions they shared. Days before, all had received notice of rent increases, some as high as 40 percent. Their apartments weren’t under rent control and few could afford such increases.

“As with labor union, the strongest weapon of tenant unions is the strike.”

A neighbor who organizes with LATU was walking by and stopped to talk with the tenants. Shortly thereafter, LATU invited a tenants’ lawyer to inform the renters of their options — to stay and fight, stay and accept, or leave. Without rent control, fighting the rent increases would require a rent strike, one justified by the unlivable state of the building. A rent strike also meant risking eviction. The tenants held two more meetings with LATU and the lawyer — at the first forming “Burlington Unidos” and choosing leaders, and at the second voting to strike for their demands: “respect, repairs, and reasonable increases.”

Over the course of the strike, Burlington Unidos demonstrated outside the office of their landlord, told their story at the neighborhood farmers market, camped outside their own apartments to remind people they might soon be homeless, and occupied the office of their unsupportive city councilperson. The tenants fought eighty eviction cases by providing evidence of their unlivable conditions. The landlord made superficial repairs, but refused to agree to rent reductions. As the cases proceeded through the courts, juries evicted three families, but found that for several others the rent strike was lawful. With sixty plus cases still to be tried, and with no likely settlement agreement, the landlord dropped the evictions and the rent increases — ending the six-month rent strike on August 31.

The story of Burlington Unidos sets a powerful example, but one that isn’t easy to follow. A successful rent strike involves more than just withholding rent. Along with exercising economic leverage, the tenants also used other forms of leverage, persuading the public to support them and directly confronting both their landlord and council-person. But the same direct action tactics applied to different situations won’t necessarily yield the same results. Participants in another LA rent strike, in Boyle Heights, pointed to a solidarity action carried out by the Los Angeles chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America — which camped outside their landlord’s house to demand that he engage in face-to-face negotiations with the tenants — as a turning point in their own fight. After the DSA action, the Boyle Heights tenants won a multiyear agreement that limits rent increases and officially recognizes their association. While Burlington Unidos deployed a similar tactic, it doesn’t appear to have been the turning point for them. In their case, their landlord forced them to accelerate the timeline of their strike when he moved forward with evictions. In response, they had to rely on the courts and on the tactic of creating exorbitant legal costs for their landlord. They were saved by the fact that the high number of tenants in the building made it too costly to evict all of them. Scale mattered.

In California, many tenants can’t rely on such economies of scale. They rent single-family homes or live in buildings with just a few units, many of which were bought up en masse by corporate landlords in the wake of the foreclosure crisis. Keeping these homes excluded from rent control was a chief aim of landlord opposition to Prop. 10. In Oakland, many tenants live in duplexes and triplexes, some of which were converted from single-family homes. In response to the atomization of tenants, the Tenant and Neighborhood Councils (TANC) initiative, operating in Oakland and neighboring cities, has approached organizing on a landlord-by-landlord rather than building-by-building basis. TANC is a newer organization formed by the Communist Caucus of the East Bay DSA, but which has stayed independent. TANC members researched the property holdings of one of their landlords, Linda Lonay, who had been harassing tenants and failing to make repairs, and who had established implicitly racist and classist restrictions on subleasing (“professionals and grad students only”). TANC then canvassed Lonay’s buildings, inviting tenants from across Berkeley and Oakland to attend barbecues and tenant meetings. Through these meetings, tenants wrote a list of demands which they submitted to Lonay anonymously, although they were sure to mention how many of Lonay’s tenants and buildings were involved in formulating the list. She capitulated immediately. On its face, the major demand — don’t restrict subleasing — might not sound significant, but the restrictions had already resulted in self-evictions and had effectively doubled the rent of remaining tenants.

The drawback to organizing by landlord rather than building is that rent strikes won’t be as powerful a tactic. Livability can vary so widely across buildings that, except in the case of slumlords who exclusively rent unsafe housing, the “implied warranty of habitability” won’t work as a shield to protect everyone involved in a strike. (The “implied warranty” is a state law that says landlords must provide safe housing — and if they don’t, tenants can withhold rent without being evicted.) However, a new state law proposed by state senator Maria Elena Durazo (a Democrat who represents a district in Los Angeles) and Tenants Together, a statewide tenants organization, could change things for tenant unions and rent strikes in California. One section of Senate Bill 529 would establish the right of tenants to “form, join, and participate in the activities of a tenants association.” But there are dangers here as well. Some older tenant unions from decades past became so encrusted with bureaucracy that they turned into the junior management partners of landlords. The law also has glaring weaknesses, such as limiting the amount that rent strikers can withhold and the length of time they can strike. Nonetheless, the law is gaining support from many nonprofits in the tenants’ movement because it would allow sanctioned tenant unions to go on limited rent strike for any grievance agreed upon by a majority of members.

RENT ZERO

But what of the broader strategic goals? What comes after a rent strike? And what of the homeless, for whom withholding rent is meaningless as tactic? For many, the horizon of the strike flows through the state. In this vision, rent strikes lead the state to adopt pro-renter legislation, enact rent control, and build low-rent social housing. It is common to hear that high rents originate in the imbalances of the capitalist market, and in an undersupply of housing. This perspective is often used to argue against rent control, by suggesting that low rents discourage construction. Advocates of social housing agree, at least in part, that housing supply is the problem, but point out that construction rarely targets the entire housing market, instead catering to middle-class and upper-middle-class renters who will maximize the developer’s return on investment per square foot. To build real low-cost housing, one would need to remove the profit motive altogether. In the words of social housing proponents Ryan Cooper and Peter Gowan, writing for Jacobin:

Municipalities would borrow money, use the money to build housing, and then rent out the resulting units . . . The housing would mostly be built by construction companies, just as public buildings like libraries already are. The management of the building could be done in-house or through contracts with building management companies.

Note that such proposals presume capitalist profit at multiple points — from the banks who lend, to the construction companies who build, to the managers who administer. As Robbie Nelson points out, in another article for Jacobin, the high cost of land in places like the Bay Area already includes capitalist profit. To provide social housing, Nelson argues, the state would have to cut out the capitalist middleman entirely and build, manage, and repair housing itself, providing it on demand to the needy, a project that homeless organizers can certainly get behind. However, we have already seen the difficulty that such legislative campaigns face. Perhaps this would be possible in a few municipalities. But the necessary taxes would be fought tooth and nail, as we’re seeing in San Francisco with Prop. C, and seem impossible at a state level, as the loss of Prop. 10 indirectly indicates. In California, the partial repeal of the famously regressive property tax reform, Proposition 13, will be the major test in the 2020 election. In my estimate, winning social housing through a struggle for socialist policy is a tenants’ movement strategy for a bygone era, one in which a sufficient fraction of capitalists were willing to compromise with proletarian militants. On the state side, the cost of purchasing land in inflated markets like the Bay Area is too great, and on the capitalist side the profits from low-rent housing infrastructure too insignificant.

“We need a permanent rent strike.”

Nonetheless, elites do sometimes compromise and retreat as individuals or in small groups, even when they are intransigent as a class. In its recent report, “Rooted in Home,” the group Urban Habitat promotes housing cooperatives and community land trusts, alongside occupations like those carried out by The Village, as “community-based alternatives to the housing crisis.” Wherever proletarian tenants can’t win social housing through the state, they might win it in fits and starts by seizing property, living on it, and maintaining it cooperatively. Removing property from the housing market by direct action — one mode of what I call “rent abolition” — could operate as reverse gentrification. While financial speculation increases the price of surrounding properties, rent abolition decreases it by putting investor confidence in jeopardy. This strategy has significant limits, as detailed by c.e. in her Commune article “Seizing the Means.” But it is still the most promising horizon for building a tenants’ movement that unites renter and homeless organizing. In the Bay Area, the indigenous, women-led Sogorea Te Land Trust has been able to purchase land through money raised by their Shuumi Land Tax. Elsewhere in Oakland, residential and commercial tenants have collectively bought their buildings for low prices, despite landlord opposition. In one story of landlord antagonism overcome, tenants living in a single-family home worked with the community organization ACCE to fight a massive rent increase. According to a social media post by ACCE, they sustained the campaign for so long — even “disrupting staff meetings at [the landlord’s] office” and sending their children to “trick or treat at the his home” — that the landlord caved and sold the home to the Oakland Community Land Trust. ACCE is even starting an Acquisition Fund so they can repeat this victory elsewhere.

Cooperativization through the market, however, will run up against the same problems as socialization through the state, since few poor renters can raise enough money to buy housing adequate to their needs. Even if they could, a large share of that money would go to the banks. Another approach has been developed by Cooperation Jackson, whose “Sustainable Communities Initiative” seeks to establish a network of interconnected projects that make possible the management and care of cooperative housing outside the market. But this doesn’t address the question of how proletarians get the property on which to form cooperatives in the first place. To do that on any meaningful scale, people will have to begin by taking housing, not asking for it or buying it. The Village’s model, in which those from whom everything has been taken unite to take rather than pay for land, is a better tactic here than cooperatives funded by Kickstarter. Charity will always be paltry compared to what we want and need. We need a thousand Villages, building not tiny homes but real housing adequate to real needs. We need to seize empty houses through whatever means necessary, and we need to have the tools and relationships to make and keep that housing livable.

Rent abolition takes for granted the basic principle of social housing: to provide homes for all, proletarians must collectively control land and housing. Rent abolition means ending land ownership in all its forms. The problem isn’t housing supply, but the entire social relationship — the relationship between proletarian tenants and landlords; between proletarian builders, plumbers, and electricians and the capitalist firms that employ them; between proletarians in general and the state. Abolishing these social relationships requires an offensive on two fronts: for free housing for all, and against attempts to profit from ownership, construction, and management. In a sense, the rent strike is not just a weapon in this struggle but the thing entire. We need a permanent rent strike. Until then, wherever people refuse to pay for shelter, wherever others join them in defense, we can see a path through the smoke.