From Radical America to Commune, a letter.

Created in 1967 to educate members of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) through the new Radical Education Project, Radical America came into being by connecting to broader insurgent movements, past and present. In discovering what it meant to be “on the left,” its editors, contributors, and readers found cultural links that had been hidden or simply not understood.

One backstory could be found in the demise of a precursor journal, Studies on the Left (1959–66), reasonably eclectic, undogmatic, and even published for a while in Madison, Wisconsin, where Radical America was based from 1967 to 1971. The historic home of Robert La Follette — storied opponent of US involvement in World War I and anti-imperialist presidential candidate in 1924 — Madison never quite lost the progressive, anti-interventionist disposition of the northern Midwest. It had professors exiled from Nazi Germany, scholarly critics of the Cold War mind, and, by 1967, thousands of semi-politicized hippies smoking dope and cursing capitalism.

Radical America came together during SDS parties, when members would collate and staple copies of the magazine, which was printed on loose sheets of paper, in the back room of the headquarters of Connections, a great underground newspaper. And it came together in hugely popular campus struggles against the Vietnam War and for Black Studies and a teaching assistants’ union, and so on. The feeling of discovering useful and interesting things — like the new forms of layout invented in the underground press and spread from city to city through the circulation of publications — was peaking in these years, with fresh inventions occurring all the time.

But the wider context was just as real. The Vietnamese were winning and the Empire was being defeated, at almost unimaginable human cost. The civil rights movement had created the setting and spirit for the New Left a few years earlier, and now the Black Power movement was declaring solidarity with anticolonial and anti-imperial struggles around the world. Demonstrations against the Soviets in Prague even looked like demonstrations in Paris or Chicago, with young rebels wearing the same clothes and listening to the same music — or at least it looked and sounded like that to us and to thousands of ordinary students who we could not have reached politically a year or two earlier.

Radical America, like SDS (for a moment, anyway), was connected to the traditions of the older Old Left. These were not the Communists of the Communist Party USA but rather the Industrial Workers of the World (Wobblies), syndicalist inspiration to our “student syndicalism” (a SDS phrase). Egalitarian and antiracist but also suspicious of vanguards and functionaries, the New Left was looking for new savants as well as new forms of organization.

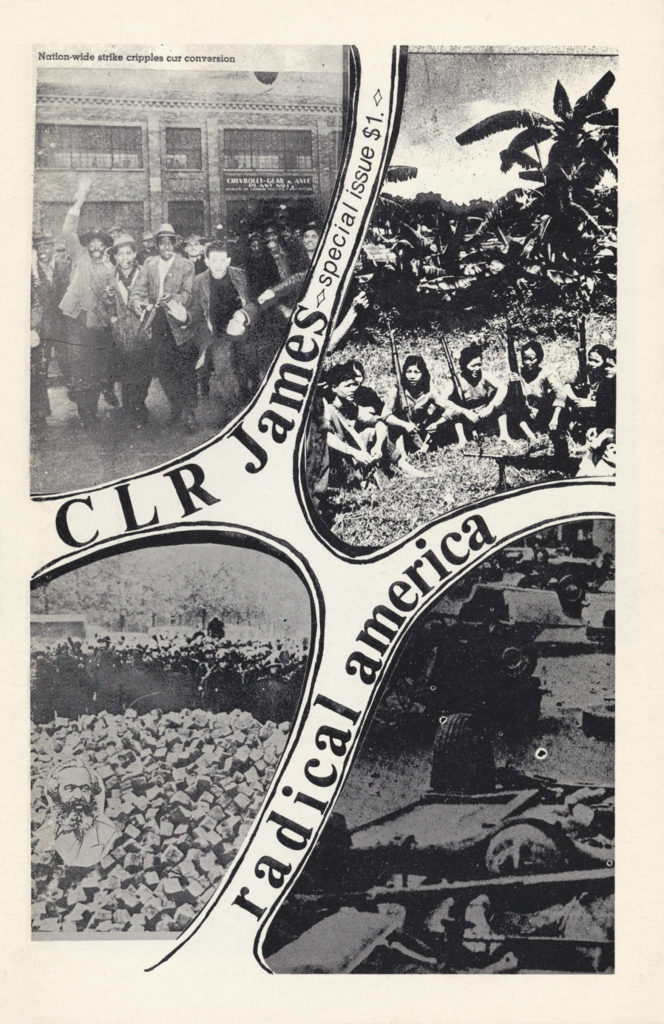

If we had one savant, it was definitely C.L.R. James. Born in 1901 in Trinidad, the black Marxist was also a Hegelian of the first rank, an intellectual leader of anticolonialism off and on since the 1930s, author of the deathless classic The Black Jacobins, and organizer among the industrial working class of Detroit. In old age, James was living proof of the idea that black people made their own history and would do so again, given the chance. An erstwhile Trotskyist broken free of all orthodoxies, James was our global explainer.

James and his scattered followers had already embraced the notion that the working class was in rapid transformation, becoming less white and male and more militant and radical when the opportunity offered. From the late 1960s to the early 1970s, strikes reached the highest point since the end of the Second World War, union leaderships were challenged as never before, and workplaces where strikes had been absent, like post offices, became centers

of mobilization.

The scholarly side of Radical America shows through, as I look back, in the publication’s determination not just “to interpret,” but to make available the fundamental documents of struggle. For example, what leaflets were issued at factory gates by the black workers’ Revolutionary Union Movement in Detroit, and what would readers learn from reprints? The same questions were asked of uprisings in Quebec, Italy, and Portugal, from which we made available photos, cartoons, and other documents, circulated by the activists on the scene, at high points of struggle.

The effort to draw materials from the past or from distant places did not always prove successful. The volunteer typesetter for the 1970 issue on Surrealism wrote back that he did not understand a single sentence! The Society of the Spectacle, translated by our Detroit anarchist printer Fredy Perlman, was a basic Situationist document but too overblown to be practical. Herbert Marcuse, that other savant, alongside James, of the age, fit uncomfortably in the pages of Radical America because in One-Dimensional Man, as he wrote in a later reassessment, he had mistaken the working class of Southern California for the working class in its totality, and nearly written them off. (We published him anyway).

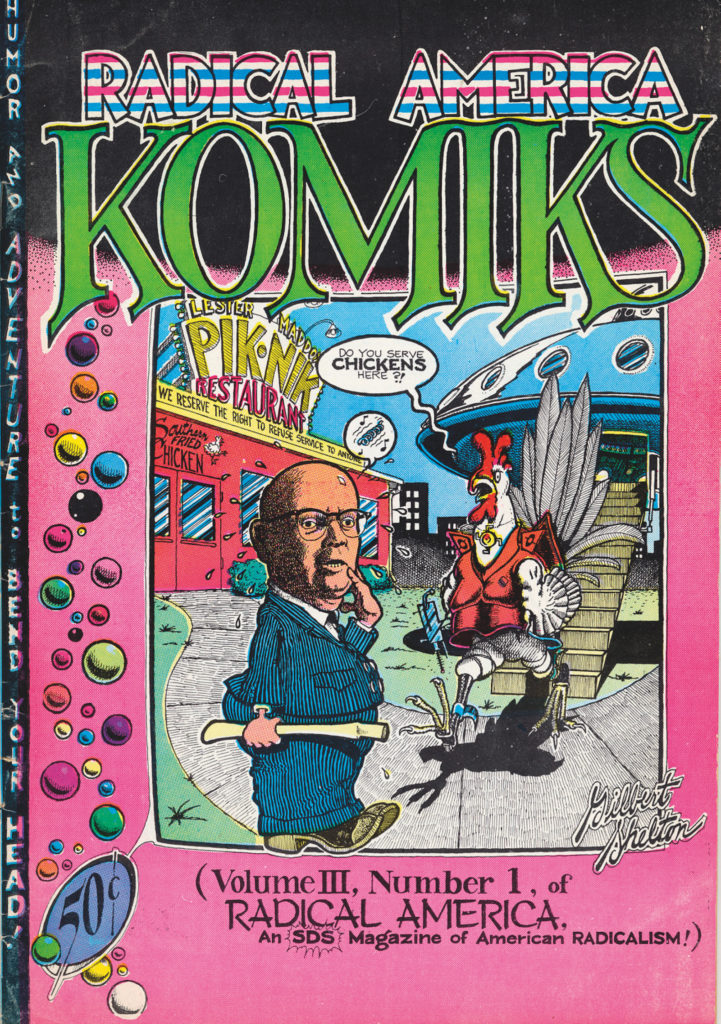

The publication of our “Komiks” issue, in 1969, took even our readers by surprise. It was our best-selling issue ever, combining antiwar sentiment with dope, featuring the Furry Freak Brothers of underground newspaper fame, and uncensored content that had never been allowed in over-the-counter comic art. Our second most popular issue, “Women,” from 1970, was more our normal style, because feminism had prompted a legion of young intellectuals to do the digging that would, eventually, create a vast field of new feminist writing across race and region. The publication of our “Black Labor” issue, featuring the League of Black Revolutionary Workers, in 1971, was our third biggest-seller and also a good example of the outlook of our project.

So we were successful, in some ways. In others, less so. The demise of SDS following the calamitous convention of 1969 would seem to make “an SDS journal” anomalous. Subscriptions went unrenewed by the hundreds and some of our campus distributors disappeared. But SDS was not the whole of our audience. It was an institution that sprung up on campuses where an alternative did not already exist, as in Berkeley.

We were collectively depressed but had been collectively depressed, beneath the surface of all the activism and intellectual stirring. Although we believed that our generation, with allies, might change the world, the reality of American life was the strength of the Empire, resting on the eagerness of ordinary people to get their share of consumer goodies. Free love and cheap marijuana could not stand up to that competition very long.

But we had sweet illusions. The Chicano movement, the women’s movement, the Native American movement not to mention Gay Liberation, were only cranking up, finding themselves. The discontent in factories and other workplaces now included veterans returned from Vietnam, disillusioned, smoking dope, their hair long.

By 1973, the illusions had largely washed away, held onto by the fragments of the New Left that had passed into the New Communist Movement and the project or “Party Building,” arguing among themselves for vanguard. These ranks included many of our best, notably former SDS leader Carl Davidson, but the world revolution was mostly receding, capital was recuperating, and despite struggles in Central and Latin America, Africa, and the Middle East, in reality the hopes of the 1960s were over. You might say that some of the strongest impulses went into “municipal socialism” and antiwar, cooperative-inclined struggles, in dozens of cities. Reaganism put an end to illusions, however, even as we political survivors struggled on.

By 1973, Radical America was nowhere near finished, though I was, obsessed with what had been lost. I had to leave the magazine, by this time based in Somerville, Massachusetts, the veritable antithesis of Madison and therefore ideal for the diaspora from the radical campus into the blue-collar community. I needed to quit just to slow down my drinking.

Was it all a dream? No, we found fresh ways to do things, to share ideas, to revive radical poetry and comic art. We did the best we could with the conditions imposed upon us. The first years of Radical America would be, for most of us on the campus and many in the community, the most promising and memorable years of our lives.

Things are worse now in a few dozen ways. But I am hoping that a new generation or two can have, is beginning to have, a similar experience, minus the unalloyed utopian expectations. Good luck, young comrades!