Beware the climate pragmatists.

New studies released in early 2019 report that the continent of Antarctica is melting more quickly and more extensively than anticipated. This process has been going on for decades, but recently picked up speed. From 2009 to 2017, the Antarctic ice sheet melted at a rate six times that which was observed in the 1980s. Since the South Pole contains nearly 90 percent of the fresh water on Earth, more rapid melting there will lead to more rapid rises in sea level, with destructive consequences for human civilization.

At the same time, interest seems to be bubbling up, even in the backwards United States, in joining a serious attempt to tackle climate change with the traditional egalitarian project of the socialist left. In the US this takes the form of the so-called Green New Deal, tying together a jobs-and-investment message echoing the FDR 1930s, and a modern agenda of zero-carbon energy systems. The Green New Deal banner has recently been picked up by rising-star Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who has linked it to other once-radical but now newly plausible ideas like dramatically increased tax rates for the very rich.

It is tempting to follow up warnings about rapid climate change with a pragmatic appeal to realistic policy proposals along the lines of the Green New Deal. What is the alternative, after all, other than giving up? As we will see, however, this way of proceeding presents us with what appears to be a frightening and demoralizing gap between the scale and immediacy of our problems, and the weakness of the social and political forces currently available to address them.

This becomes clear when we examine the document that, just a few months ago, shaped most topical climate journalism: the October 2018 report of the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which describes the potential impacts of global warming at a scale of 1.5 degrees Celsius. This is a detailed and comprehensive publication, and few people have the patience or knowledge to wade through its pages upon pages of charts and graphs. But the basic message of the report is as sweeping as it is terrifying. Even the report’s title, “Global Warming of 1.5°,” is misleading in its understatement. The report observes that the Earth is already nearly one degree warmer relative to a pre-twentieth-century baseline.

“Some are convinced instead that they can hide out in their walled compounds, protected by their killer drones, while the rest of us scramble for what’s left of a ruined Earth.”

Moreover, 1.5 degrees of warming represents an optimistic lower bound figure, achievable only in the context of “ambitious mitigation actions.” The point of the report, then, is not to argue that 1.5 degrees of warming is possible, but that it is probably inevitable, and the only question is whether, in fact, we will experience significantly greater warming than that baseline. The report’s framing chapter concludes ominously that, in fact, “there is no single answer to the question of whether it is feasible to limit warming to 1.5°C and adapt to the consequences,” despite the nominal commitment of the Paris Climate Agreement signatories to this figure.

If the IPCC report is any kind of landmark, it will be because it puts an end to a basically fictitious debate about the empirical reality of human-made climate change and instead focuses discussion on probable outcomes and possible adaptive strategies. The debate is fictitious because one side presumes, disingenuously, to base their arguments on uncertainty about climate science, rather than admitting themselves partisans of a political and class project designed to ensure that the costs of ecological chaos are borne exclusively by the powerless.

In much of the world, this has long been obvious, but in the United States the persistence of a prominent denialist wing on the right makes it necessary to briefly clarify this point. Useful idiots aside, it is unwise to presume that those who deny the reality of human-caused climate change are genuinely concerned about scientific accuracy.

More helpful is examining the apocalyptic fantasies of the super-rich, who have begun to invest in various schemes to hide out from what they see as the looming collapse of civilization. In the case of the Silicon Valley billionaire Peter Thiel, this has taken the form of fantasies about “seasteading” an independent floating city, and investment in land in the safety of New Zealand, alongside his super-rich peers.

The Trump administration, in its typically hamfisted way, has clarified the true stakes of the climate change debate, in the course of its recent battle against strict California car emissions restrictions. As part of this jockeying for position the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) issued a report with a shocking revelation of the administration’s view of the future, predicting that not only was further warming inevitable but that it was likely to be on the order of four degrees by 2100, not the comparatively modest 1.5 of the IPCC report and the Paris accords.

The purpose of this alarming declaration, in the context of the NHTSA report, was to claim that strict emissions standards like California’s are unlikely to make a noticeable impact relative to the scale of global warming, and that such standards are therefore economically unjustifiable. But while notable in its crudity, this “smoke ’em if you got ’em” attitude aligns with the perspective of capitalist elites, particularly in the extractive industries, whose primary goal is to avoid paying the cost of climate mitigation in the form of new regulations or taxes.

Here the intersection of the Trump administration with the doomsday-prepping Thiel types becomes significant, as it puts the lie to the comforting eco-liberal bromide that, really, we’re all in this together and have an interest in protecting the Earth for all of our sakes. It’s clear that not everyone believes this, and some are convinced instead that they can hide out in their walled compounds, protected by their killer drones, while the rest of us scramble for what’s left of a ruined Earth. They may well be deluded in this belief—captive to a bourgeois ideology that sees capitalists as individualist wealth creators rather than people dependent on the labor of millions. But we can’t count on them to figure that out before they take us all down with them.

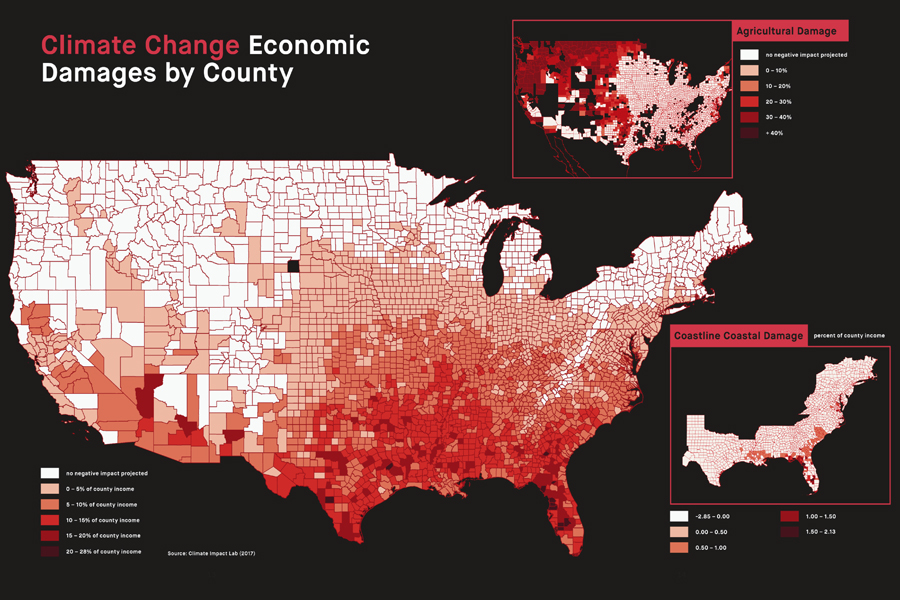

This brings us back to the IPCC report, and its catalog of environmental horrors. It is a valuable resource if only for its breadth, describing a crisis that can only in the most superficial way be summarized as “warming.” The collapse of marine ecosystems, reefs and fisheries, flooding of densely inhabited coastal areas, falling crop yields, among other calamities, make their appearances. Other research has examined the impact of sustained “wet bulb” temperatures (think heat plus humidity) surpassing 32 degrees Celsius (about 90 degrees Fahrenheit). At such temperatures, it becomes impossible to carry out ordinary activities outside, as the human body becomes physically unable to cool itself. The result is mass death from overheating, and ultimately the possible abandonment of some regions, including densely packed parts of South America, India, and China.

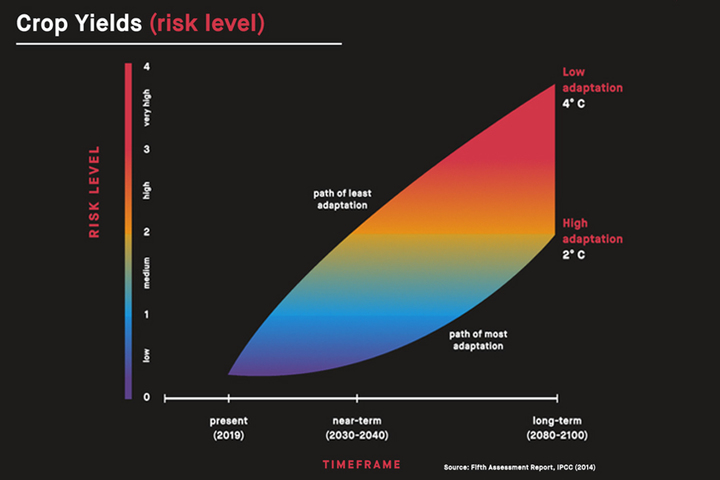

One could go on at great length about this and other disasters foreseen in the IPCC models, but in many ways this is beside the point. The general lesson is conveyed effectively by a series of simple charts in the October 2018 report (figures 3.19–3.21). These are scales showing the effect of different degrees of warming on a variety of systems including among other things “coastal flooding,” “terrestrial ecosystems,” “crop yields,” “heat-related morbidity and mortality,” and “ability to achieve sustainable development goals.” Severity of impacts is shown for increases ranging from below one degree up beyond two degrees. For most of these areas, the colored scale quickly reaches into the red, for “severe and widespread impacts/risks,” and beyond to purple, “very high risks of severe impacts and the presence of significant irreversibility . . . combined with limited ability to adapt due to the nature of the hazard.”

And recall that these are essentially best case scenarios for what might be possible if rapid adaptation in line with the Paris agreements proves to be feasible. It barely touches upon the severe levels of warming envisioned by Trump’s NHTSA, let alone the even more extreme scenarios envisioned in the event that various ecosystem feedback loops are triggered, such as the rapid release of Arctic permafrost methane.

The farthest the IPCC will go is the realm of “warming up to 3°C” (table 3.7), which is frightening enough. There we are given dire warnings about rainforests (“potential tipping point leading to pronounced forest dieback”), heat (“substantial increase in potentially deadly heatwaves very likely”), and agriculture (“drastic reductions in maize crop globally and in Africa”), among others.

So now we come back, finally, to the Green New Deal, or whatever other package of plausible social democratic reforms one prefers. Now we are back in the realm of such sedate ideas as the “smart” electricity grid, renovating buildings for energy efficiency, and windmills and solar panels for all. Laudable goals all, and yet depressingly scant gruel after any time spent gorging on the vivid projections of the scientists.

There is also the problem that tends to arise when multiple separate political goals are packaged together into one big trick that is intended to achieve them all. In the case of the Green New Deal, this problem arises in particular from the relationship between the redistributive and ecological tasks it must take on. As envisioned by Ocasio-Cortez, for example, the Green New Deal is meant to be a job-creation program, with the newly popular “job guarantee” taking a central role.

It is easy to imagine in advance that jobs for all and infrastructure investment walk hand in hand in harmony. But in practice it is impossible to ensure that the scale of labor and the particular skill sets needed will align with the masses clamoring for incomes. And whenever such “dual mandate” projects come into conflict with themselves, one of the mandates will tend to win out over the other. If the job guarantee ends up largely a make-work program, it is hard to see how it can also be Green. Other, not quite as mainstream ideas, such as working time reduction and the Universal Basic Income, may need to be brought on board as the GND idea comes closer to fruition.

“The Earth is on fire as we bicker about what kind of fire extinguishers to buy.”

But this all still feels like fiddling around at the edges. The Earth is on fire as we bicker about what kind of fire extinguishers to buy. The sheer urgency of the climate issue strongly militates, for the pragmatically minded, toward a form of “do something-ism” that veers headlong into whatever project can achieve a majority, however inadequate it might be.

There is, of course, nothing really pragmatic about settling on a compromise that doesn’t solve the problem it claims to. But the equally unsatisfying alternative is a kind of intransigent, insurrectionary maximalism, shouting portents of doom from the rooftops. It is tempting to go onto Twitter, or into the pages of Commune, to deride those who can’t see the need for immediate action and revolution, by any means necessary.

So we come back around to the old standard, What Is To Be Done? The unsatisfying but probably sole possible answer, of course, is: everything. The Green New Deal moves on, but there’s something to be said for those who prefer the work of building more local, communal projects of self-sufficiency and mutual aid. While no substitute for contesting the commanding heights of the economy, these projects can gradually build the trust, and the collective capacity, for the kind of truly militant mass action that is ultimately required. Then, of course, there is the slow building of transnational links; capital and climate are implacably global, while the gradually reviving left remains depressingly parochial, in the rich countries especially.

So perhaps, the only way to work for a sustainable post-carbon world is not to actively focus on it. Perhaps we must tactically look away from that impossibly large chasm between our politics and our planet’s needs. If the social force necessary to make a better world does not yet exist, we can only try to create it. That may mean rallying behind the Green New Deal, or building our local network of communes, or both. It will also mean occasional dramatic acts of direct action, attacking the infrastructures and institutions of fossil capital directly—proving to them that their dreams of hiding from the desperate masses in their walled compounds are doomed.

That can’t be everyone’s task, nor should it be if we are to avoid degenerating into adventurism. But it will be someone’s. If we make it to the other side in one piece, someone will be remembered as the Frederick Douglass of climate change. But so too will someone be the John Brown. It is in that sense, at least, that we really are in this together.