Don’t say rest in peace, say fuck the police.

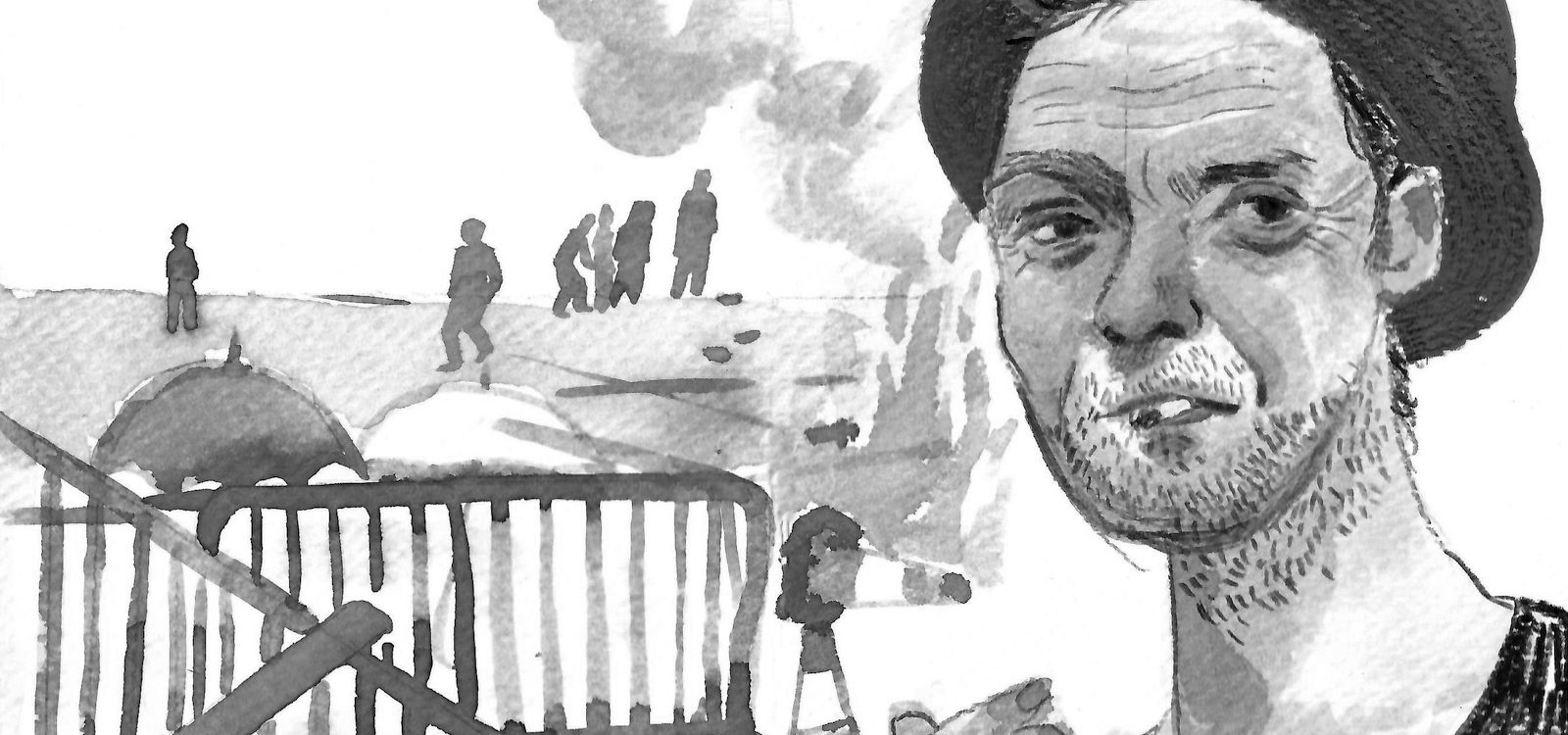

Sean Bonney died this November in Berlin at the age of fifty. He would likely reject the reduction to national tags, but he was a great poet of political militancy in a particularly British vein. No one captured the banal agony of Thatcherism and its aftermath with the same punk fury; no one was more repulsed by Third Way liberalism; no one chronicled the riots that bloomed after the police murder of Mark Duggan with such a feel for tear gas, what it is, how it tastes, what it means, the atmosphere of dark and temporary joy. His poetry is tear gas turned upside down and set on its feet. He came to London first to take part in political movements, moved through a series of scenes, radical politics and music and poetry. He got infamous for saying, “When you meet a Tory on the street, cut his throat. It will bring out the best in you,” because that is how infamy works; the poetry is for all of that forever wry and sardonic and always with one eye on the cops and the other on the grave. He was also renowned for writing one of the greatest fuck the police poems, and he takes his place with not just Amiri Baraka and Diane di Prima, but with N.W.A. and Miguel James and Lil Boosie. He also takes his place or remains with a couple generations of poets writing in a lineage they share with him and that goes back to the Ranters and William Blake and passes into the future. The remarks of a small fraction of them are collected here; they can hardly measure his influence or our loss.

Things Sean taught me: He taught us how to read. He introduced us to everything. He introduced us to Milton and Baudelaire and Brecht and Blake and Michel and Trakl and Pasolini and Rimbaud and Cesaire and Gogou and Baraka and di Prima and Wieners and Berber, and he rewrote every single one of them and made us want to rewrite every single one of them too, on laptops and typewriters and notepads and across the insides of government offices and on the surfaces of our bodies. He introduced us to collage and cut-up and rhythm & blues and geometry and harmony and rock ’n’ roll dance moves and Fall lyrics and Class War and revolutionary letters and the cosmology of Louis-Auguste Blanqui. He taught us about birdsong and dawn and Thatcher and ACAB and the esoteric properties of numbers. He wrote a poetry of irrefutable moral truth and performed it as if he had just listened to everything that history had to say and this was what he fucking thought of it, yeh; and history never had any goddamn answer; and you can hear his cadences and his attack and his velocity mutated and transformed in every single one of us, and he will live on forever in our muscle memories and our nervous systems as well as our thoughts, and he taught us most of what we know about those things as well. Sean taught me that poetry can absolutely bring back the dead because I saw his poetry do it so often, in so many rooms, on so many occasions, over so many years, in front of so many audiences, for my whole adult life. He taught all of his revolutionary and leftist and anticapitalist listeners just what “our politics” mean. I can’t believe that I’ll never hear him read again. He introduced us to spite and class hatred and political murder and pink filth and sunflowers and black and white skies, and he taught me about brevity and exhaustion and world politics and the whole reality of my senses. The blog where he posted his poems was like a second, slower heartbeat for me. Without his poetry, I don’t know who I would be. Every feeling I am capable of having bends through it. I love you so, so much, Sean. You did so much to derange our senses. They will never be the same without you. There will never be anyone like you.

Danny Hayward is putting together an archive of out-of-print poetry at pxxtry.com.

I’m not supposed to bring up the fuck the police poem & at a moment where both uprisings are happening everywhere & everyone is online, some people are going to roll their eyes at the idea of another fuck the police poem, but that just means they haven’t read Sean Bonney’s fuck the police poem. Really, though, there is nothing I can say or write about Sean Bonney that will get at what the world has lost — that relation between Sean as an anti-racist proletarian & the world in the grip of capitalism & crises that he could write about so well. I am going to miss that. Sean understood, as very few writers do, that it isn’t enough to write about crisis; you have to be the crisis, which no one can do alone. When I first met him in 2013, Sean was the only one, among the UK poets he was with, to have gone out during the 2011 London Riots. I never figured out which had come first for him: was it the streets? Or was it the poetry? That’s probably the nicest thing I will ever say about someone most known for their poetry.

Wendy Trevino is the author of Cruel Fiction.

The literary and revolutionary worlds to which Sean Bonney and his poetry still speak (or shout and snarl, more accurately) have lost one of our leading flames, though his spirit still burns through riotous nights for those committed to anarchist life and culture.

Coming out of punk rock and anarchist scenes, Sean brought a more performative and combative ethos to post-Thatcherite London, always remaining steadfastly contrarian — not only to the pieties of academicized Anglophone poetry but also to the prisons of work and careerism. Sean’s devotion to the poet’s life — enmeshed in the refusal of work as much as the forged affinities of anarchist practice — was difficult to maintain in an era of austerity and riot police, but was central to his poetics, developed in conversation with other revolutionary traditions of all sorts. Thus, his early rewrites of Baudelaire & Rimbaud evolved in his later work to his exemplary Letters, missives to an imagined interlocutor that fused poetic invective with a critical analysis of the contemporary order unique in its political-poetical force. In recent years, he’d also turned to anarchists and poets such as Katarina Gogou and Diane di Prima, in addition to Amiri Baraka and the Afro-Caribbean surrealists, a project of recovery and reanimation of radical histories which he termed “militant poetics.”

He fused a rigorous critique of the existing order in its totality with the joyful (and militant) pleasures to be found in, say, the cry of Albert Ayler’s saxophone or the sound of a brick breaking storefront glass, those negations of capitalist clock-time he transcribed into what he called a “prosody of riot,” which for Sean also revealed new possibilities emerging out of a shared refusal of the given, as creative as it is destructive. If there is indeed a poetics of riot — opposed to what Sean called “police realism” — it is to be found in his prose and poetry, and exemplified in his often chilling public performances.

Sean continues to be one of the most important guides for imagining avenues beyond our current cultural-political impasses. His friendship and his work will be sorely missed, though he leaves behind both a legacy and a method that we can still draw energy from. As Sean may have put it: mourn the living, fight for the dead.

David Buuck lives in Oakland, where he edits Tripwire, a journal of poetics.

Sean Bonney shows us that “Somewhere are Angels. Angels have claws. Dogs are everywhere.” Sean Bonney shows us that a poem is not a riot, not a strike or blockade or commune or brick or barricade. But, he reminds us, we write and read them regardless. For one, they allow us to commune with the dead: “It’s a weird game, to ask advice from the dead as they walk toward us, telling us our fortunes from their enclaves in the landscapes our poems try to describe.” Sean Bonney tells us that “the lyric I — yeh, that thing — can be (1) an interrupter and (2) a collective.” And so: we search for the limits of our subjectivity; probe in the dark (for “interpreters. commies. thieves”); open our ears and our eyes to the chaos that we produce but are not subsumed by. Sean Bonney says that we should always celebrate the death of Tories. Sean Bonney shows us that letters can be intimate expressions of rage and refusal and care, all things required for revolution. Sean Bonney tells us “a snare is come among us / there are none to comfort us.” And yet: “our bodies are still here.” Sean Bonney shows us something about fear and about the danger of selling ourselves out. Our enemies can creep inside of us, eat us from within, occupy our mouths, change our names if we are not careful. Sean Bonney tells us: “I can’t lie. Things will get harder, / but keep at it. Despite our violence / our addictions. All this burning earth.” Sean Bonney shows us how to hate fascists — “And the cops, of course.” We must “reinvent time. reinvent violence. then / listen, go at those bastards like the furies. / only then will you disappear / only then will you learn the magic.” Sean Bonney warns us: “There are people who came here to become managers and became managers.” (We remember this as we peer down the hallway, crane our neck from the office door, face the flat affect of the executive team.) Sean Bonney knows our enemies have names; our neighborhoods have names (“Kreuzberg. Exarchia. Hackney”); we call each other names, give our dreams names in an effort to share them; not only metaphors but weapons are names; there are names we cannot say aloud but screech or “powder-gasp” in lieu of freedom or poetry; cities have names even when, or especially when, they burn.

Snack Syndicate (Andrew Brooks and Astrid Lorange) are a critical art collective who live and work on Wangal land in the Eora Nation (Sydney, Australia). They make texts, objects, events, and meals.

When I moved to London in my early twenties, Sean and Jeff Hilson were running the Xing the Line reading series. They made it feel like if writing and reading out poems was a silly thing to do, then we could all be okay with that. Also, they didn’t perv on anyone — they treated me like a poet with a brain. I read Hölderlin because of Sean, because he let me know that anyone could afford to be moved by mad, millenarian, cosmic fragments.

In 2014, Sean O’B and I went to visit Sean and (the brilliant, gorgeous) Frances in Calgary, where they were staying with Frances’s parents. Sean hated Calgary. But he did like Tubby Dog, a self-described punk-rock hot dog shop on the main strip, and “the only thing worth leaving the house for.” So we went to Tubby Dog, and then Sean shared his whiskey with us all night.

I now live in Sean’s and Frances’s old stomping ground in Walthamstow, with O’B. Every day there’s a new florist pop-up selling even more suffocating arrangements of eucalyptus stems. The Rose and Crown is still here though. I remember walking past it one time on the way to Sean and Frances’s flat, years before I moved to Canada, and thinking that pub looks shit. It’s my favourite: a Victorian boozer with bright lights and all ages, and it reminds me of Sean though I don’t know if he even went there.

The last time I saw Sean was when he visited London in early 2018. I was on strike and Sean came to read for us on the picket line at King’s. Holly, Tom, Nisha, Luke, Emilia, Rob, Will, Edmund, a bunch of others were there on the Strand with the buses running past. Lots of students were there too. He read from Letters Against the Firmament through a megaphone, and it was all just right. The students whooped when he read the “fuck the police” lines. Afterwards he told me that was the first time he’d enjoyed giving a reading in ages, and that he wanted to move back to London “for when things kick off.” Oh Sean, I wish you had and they would. We love you. You were always right to be incandescent.

Often I have it, language

anger, she said, was enough and approved by Apollo—

If you have love enough, then, go on, rage out of love.

Amy De’Ath writes on contemporary poetry, gender, and Marxism, and has published a number of poetry chapbooks. She is working on her first collection of poems.